Current management of non-palpable testes: a literature review and clinical results

Introduction

Cryptorchidism is the most common genitourinary anomaly in boys with an incidence of 3% in full term neonates, rising to 30% in premature boys (1). During the first months of life, testis may continue their normal descent process. Cryptorchidism occurs in 1–2% by 3-month of age (2) and decreases to 0.8–1.2% in boys at 1-year-old (1,3).

Nearly 20% of the non-scrotal testis is not palpable (4). A testis may be non-palpable because of intra-uterine demise (vanishing testis), agenesis (true monorchia), intra-abdominal location, or inguinal location with a different grade of dysplasia or atrophy (5).

Treatment of the cryptorchid testis is justified due the increased risk of infertility and malignancy as well as the risk of testicular trauma and a possible psychological stigma on patients and their parents (6).

Males with undescended testes have a lower sperm count and lower fertility rate. This rates increases with bilateral involvement and with age at the time of orchiopexy. Germ cell density decreases over time, beginning as early as 1 year of age (7).

Studies suggest that neonatal gonocytes transform into the putative spermatogenic stem cells between 3 and 9 months (8).

The incidence of carcinoma in situ is determined to be 1.7% among patients with undescended testes (9). Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment of undescended testis are needed to preserve fertility and to prevent testicular malignancy (10).

Diagnosis

It’s essential to make a correct diagnosis, for ensuring that the patient receives proper treatment at the appropriate time (11). The initial diagnostic tool is physical exam, which should be done by a paediatric surgeon or paediatric urologist.

Hypertrophic contralateral teste could be correlated with absent teste or atrophy (12,13). Nevertheless, this does not preclude surgical exploration since the sign of compensatory hypertrophy is not specific enough (14).

There are radiologic examinations which could be used for the diagnosis of non-palpable testis, such as ultrasound scan, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and venography. However, it has been shown that surgical exploration is the definitive investigation (15).

In expert hands, ultrasonography has a high positive predictive value for inguinal located testes, such as 91% and with a 78% of sensitivity (16). When ultrasound done by a paediatric expert locates a testis in an inguinal location, a primary inguinal exploration can be considered, preventing an unnecessary diagnostic laparoscopy (17).

Conventional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has similar accuracy rates to ultrasound, around 85%. If the conventional MRI is combined with diffusion—weighted sequences, the rates increases with 96% accuracy, 96% sensitivity and 100% specificity (18).

Imaging modalities are not sensitive enough and examination of a non-cooperative or obese child can be difficult in the clinic setting.

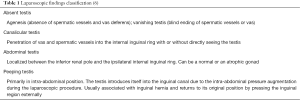

Laparoscopy has become the “gold standard” diagnostic method for non-palpable testis. In addition to being a diagnostic method, it has been an option for treatment this condition (7,19,20,21,22) (Table 1, Figure 1).

Examination under anaesthesia allows for careful examination and in some cases changes the diagnosis from a non-palpable to a palpable testis in the inguinal canal, not requiring laparoscopy. But even under anaesthesia it can be difficult to palpate a nubbin testicular in the scrotum, especially in the obese child (20,23).

If the testis remains non-palpable with the patient awake, a careful examination under anesthesia allows palpation of testis in approximately 20% of cases (11,21).

Studies show that although a non-palpable testis was diagnosed by a paediatric surgeon and urologist, an inguinal testis was found in 21–85% of the patients during surgery (4).

Management

The management of non-palpable testes is surgical, which could be challenging and controversial.

Orchidopexy is indicated if the testis is not located in the scrotum after 6 months as it improves fertility rates and allows close monitoring for the development of possible testicular masses (20).

However, if a testis remains non-palpable at 3 months of age, it is unlikely to become palpable by waiting another 3 months. Therefore, in our view, diagnostic laparoscopy could be considered from 3 months of age (24).

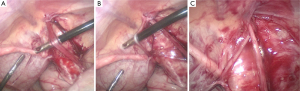

Laparoscopy in the management of non-palpable testes provides a definitive diagnosis by the direct view of spermatic bundle and testis (22), and it also could be the treatment armamentum.

Low intra-abdominal testes are described to be located less than 2 cm from the internal inguinal ring; high testes are more than 2 cm (6).

Differenciate intra-abdominal testes in low and high position might be difficult, so, orchiopexy in two-stage maybe a better approach in these cases.

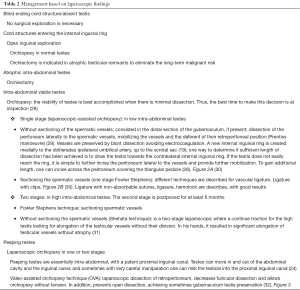

In intra-abdominal testes, treatment is described in one or two stages.

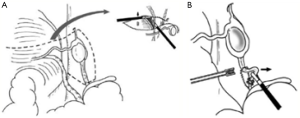

Fowler Stephens, in 1959 describes vascular ligature in one-stage, to aid mobilization, thereby leaving the testes to rely on collateral blood supply along the vas deferens. This technique had a rate of atrophy around 50% (25). Ransley in 1984 advised a two-stage procedure with an interval between vessels ligation and testicular mobilization, with good results (26). In 1994, the laparoscopic Fowler-Sthephens is described. A successful outcome is recorded in 83%. Atrophy occurred in 8.8% and ascent in 8.8% (27) (Table 2).

Full table

Results

All the techniques described have shown different results.

Surgical success should be defined as a viable testis, located dependently in the scrotum to allow for subsequent physical examination (28).

The two-stage laparoscopic Fowler-Stephens approach is currently the most popular technique for intra-abdominal testes, with success rate of about 80–85% (27,33,34).

A meta-analysis comparing different techniques for non-palpable testes in 1995, found success rates of 89% for inguinal testes, 67% for single-stage Fowler-Stephens, and 77% for two-stage Fowler-Stephens (33).

In 2001, a multi-institutional analysis of laparoscopic orchiopexy, found higher failure (atrophy and poor position) in the single-stage Fowler-Stephens (25,9%) versus the two-stage Fowler Stephens (12,1%) (35).

Shehata technique shows 90% success for boys aged less than 2 years and only 64% for cases older than 6 years, highlighting the importance of operating at a younger age (31).

In difficult palpable testes and peeping testes, OVA technique shows 100% of success (32).

Our experience

We review between 2000–2009, in two centers (Dr. Exequiel Gonzalez Cortes Hospital-Dr. Luis Calvo Mackenna Hospital), 77 patients with 90 non-palpable testes. None testes were found under anesthesia. All of them were subjected to laparoscopy.

In 38 testes (42%), the vas and deferens go into the internal inguinal ring, so, inguinal exploration was made. 13 (34%) were atrophic/evanescent which required orchiectomy. 23 (66%) required orquidopexy.

A total of 52 testes (58%) were intra-abdominal. A total of 14 testes (27%) were atrophic/evanescent which required orchiectomy. A total of 38 testes (73%), had good size. Twenty one required two-stage Fowler-Stephens and 17 required laparoscopic assisted orchidopexy.

In follow-up, we found 3 atrophic testes, 2 Fowler-Stephens and 1 laparoscopic assisted orchidopexy.

In a non-published study of further follow-up of our data, from 2010 to 2014 our atrophic testicular rate increased from 4% to nearly 8%. Therefore, in our centre we are currently running a prospective study since January 2015. All non-palpable testes are undergoing a 2 stage follower stephens approach. In this 18 months, with 10 boys having the 2 stage completed there is no atrophic teste so far. Acknowledging the short time follow-up and the few cases of this ongoing study, our initial reports support the current literature suggesting the 2 stage surgery as the one with best long-term results.

Discussion

Cryptorchidism is a common consult in pediatric surgery and urology. Twenty percent of them are non-palpable testes.

Our goal as surgeons is to find them and secure their proper treatment, because of the risk of infertility and cancer.

There are many alternatives to study these patients prior to surgery: physical examination, even under anesthesia, radiologic techniques. Surgery is the Gold Standard for both diagnosis and therapeutic.

Sensitivity of physical exam depends on surgeons’ experience, morphology of the patient and testes location.

Several radiologic diagnostic tools have been used to study non-palpable testes: ultrasonography, scanner, MRI. Is useful in those that testes are not found by physical exam, but that locates on inguinal canal. This could prevent laparoscopy.

Definitive diagnosis is made by laparoscopy. Laparoscopy provides direct visualization of testicular vessels and locates intra-abdominal testes and allows treatment of this pathology.

The principle of traction has been used in the past, but was abandoned due to high rate of atrophy.

Then, Fowler Stephens describes their technique, sectioning the vessels and descent in one-stage. Better results are achieved in two-stage with lower rates of atrophy.

For low intra-abdominal testes, descend in one-stage without sectioning the vessels has a high success rate.

For high intra-abdominal testes, the descend in two-stage seems to be the better choice.

For peeping testes, it could be a two stages or a video assisted orquidopexy

Conclusions

The laparoscopic approach is still the first procedure to face a non-palpable testes, for diagnosis and therapeutic.

The surgical technique for non-palpable testes is still controversial.

We propose a management algorithm for non-palpable testes (Figure 4).

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Berkowitz GS, Lapinski RH, Dolgin SE, et al. Prevalence and natural history of cryptorchidism. Pediatrics 1993;92:44-9. [PubMed]

- Virtanen HE, Bjerknes R, Cortes D, et al. Cryptorchidism: classification, prevalence and long-term consequences. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:611-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scorer CG. The descent of the testis. Arch Dis Child 1964;39:605-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tasian GE, Copp HL. Diagnostic performance of ultrasound in nonpalpable cryptorchidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011;127:119-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Diamond DA, Caldamone AA. The value of laparoscopy for 106 impalpable testes relative to clinical presentation. J Urol 1992;148:632-4. [PubMed]

- Denes FT, Saito FJ, Silva FA, et al. Laparoscopic diagnosis and treatment of nonpalpable testis. Int Braz J Urol 2008;34:329-34; discussion 335. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Docimo SG, Silver RI, Cromie W. The undescended testicle: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician 2000;62:2037-44, 2047-8. [PubMed]

- Hutson JM, Li R, Southwell BR, et al. Germ cell development in the postnatal testis: the key to prevent malignancy in cryptorchidism? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013;3:176. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giwercman A, Bruun E, Frimodt-Møller C, et al. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopathological abnormalities in testes of men with a history of cryptorchidism. J Urol 1989;142:998-1001: discussion 1001-2.

- Guo J, Liang Z, Zhang H, et al. Laparoscopic versus open orchiopexy for non-palpable undescended testes in children: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Surg Int 2011;27:943-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Budianto IR, Tan HL, Kinoshita Y, et al. Role of laparoscopy and ultrasound in the management of "impalpable testis" in children. Asian J Surg 2014;37:200-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mesrobian HG, Chassaignac JM, Laud PW. The presence or absence of an impalpable testis can be predicted from clinical observations alone. BJU Int 2002;90:97-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braga LH, Kim S, Farrokhyar F, et al. Is there an optimal contralateral testicular cut-off size that predicts monorchism in boys with nonpalpable testicles? J Pediatr Urol 2014;10:693-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz RS, Kaptein JS. How well does contralateral testis hypertrophy predict the absence of the nonpalpable testis? J Urol 2001;165:588-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Hali W, Anderson P, Giacomantonio M. Management of impalpable testes: indications for abdominal exploration. J Pediatr Surg 1997;32:918-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vos A, Vries AM, Smets A, et al. The value of ultrasonography in boys with a non-palpable testis. J Pediatr Surg 2014;49:1153-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nijs SM, Eijsbouts SW, Madern GC, et al. Nonpalpable testes: is there a relationship between ultrasonographic and operative findings? Pediatr Radiol 2007;37:374-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abd-ElGawad EA, Abdel-Gawad EA, Magdi M, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for detection of non palpable undescended testes: Diagnostic accuracy of diffusion-weighted MRI in comparison with laparoscopic findings. The Egyptian Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2015;46:205-10. [Crossref]

- Bittencourt DG, Miranda ML, Moreira AP, et al. The role of videolaparoscopy in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach of nonpalpable testis. International Braz J Urol 2003;29:345-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez KW, Dalton BG, Snyder CL, et al. The anatomic findings during operative exploration for non-palpable testes: A prospective evaluation. J Pediatr Surg 2016;51:128-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsu HS. Management of boys with nonpalpable undescended testes. Urological Science 2012;23:103-6. [Crossref]

- Papparella A, Romano M, Noviello C, et al. The value of laparoscopy in the management of non-palpable testis. J Pediatr Urol 2010;6:550-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Frimberger D, Malm-Buatsi E, Kropp BP, et al. Reliance of preoperative scrotal examination versus final operative findings in the evaluation of non-palpable testes. J Pediatr Urol 2015;11:255.e1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yankovic F, Mushtaq I. Laparoscopic Two-Stage Fowler-Stephens Procedure For Undescended Testis – A Personal Perspective. Dialogues in Pediatric Urology 2012;33:5-6.

- Fowler R, Stephens FD. The role of testicular vascular anatomy in the salvage of high undescended testes. Aust N Z J Surg 1959;29:92-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ransley PG, Vordermark JS, Caldamone AA, et al. Preliminary ligation of the gonadal vessels prior to orchidopexy for the intra-abdominal testicle. World J Urol 1984;2:266-8. [Crossref]

- Alagaratnam S, Nathaniel C, Cuckow P, et al. Testicular outcome following laparoscopic second stage Fowler-Stephens orchidopexy. J Pediatr Urol 2014;10:186-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmer LS. Single-Stage Laparoscopic Orchidopexy. Dialogues in Pediatric Urology 2012;33:2-4.

- Sfoungaris D, Mouravas V, Petropoulos A, et al. Prentiss orchiopexy applied in younger age group. J Pediatr Urol 2012;8:488-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang M, Franco I. Laparoscopic Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy: the Westchester Medical Center experience. J Endourol 2008;22:1315-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shehata S, Shalaby R, Ismail M, et al. Staged laparoscopic traction-orchiopexy for intraabdominal testis (Shehata technique): Stretching the limits for preservation of testicular vasculature. J Pediatr Surg 2016;51:211-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sepúlveda J. Video-Assisted orchidopexy (OVA): is it the technique of choice for difficult palpable undescended testicles? Rev chil urol 2013;78:13-8.

- Docimo SG. The results of surgical therapy for cryptorchidism: a literature review and analysis. J Urol 1995;154:1148-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stedman F, Bradshaw CJ, Kufeji D. Current Practice and Outcomes in the Management of Intra-abdominal Testes. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2015;25:409-13. [PubMed]

- Baker LA, Docimo SG, Surer I, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of laparoscopic orchidopexy. BJU Int 2001;87:484-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]