A novel polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 1 (PNPT1) gene variant potentially associated with combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 13: case report and literature review

Highlight box

Key findings

• An infant of Chinese identified with a novel polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 1 (PNPT1) variant may be associated with combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 13 (COXPD13).

What is known and what is new?

• COXPD13 results from mutations in the mitochondrial PNPT1 gene. However, none of COXPD13 is reported in China.

• We present the clinical and molecular genetic features of an infant of Chinese descent identified with a novel PNPT1 mutation, which may be associated with COXPD13.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The novel PNPT1 gene variant, c.1033A>G (p.K345E), is predicted to disrupt the secondary and tertiary structures of the PNPT1 protein, impairing its normal function. This disruption may lead to mitochondrial RNA processing defects, contributing to the development of COXPD13.

Introduction

Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency (COXPD), a rare autosomal recessive disorder, results from mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) deficiency (1,2). It often leads to multi-system dysfunction and is characterized by a wide spectrum of manifestations, varying disease courses, ages of onset, and outcomes. COXPD is genetically heterogeneous and can be caused by mutations in multiple pathogenic genes (3,4). To date, 58 types of COXPD (COXPD1–COXPD58) have been identified based on variants in different genes (4). COXPD13, caused by a defect in the polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 1 (PNPT1), is a rare mitochondrial disorder (5,6). Typically, it manifests during the neonatal period or infancy, presenting with severe encephalomyopathy, cardiomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and liver dysfunction. The disorder usually involves normal early childhood development, followed by sudden onset in infancy, characterized by feeding difficulties, dysphagia, muscle weakness, involuntary movements, muscle atrophy, abnormal eye movements, clouded vision, nystagmus, and decreased reflexes (5-9). While 15 cases have been reported globally, none have been documented in China. In this study, we analyzed the clinical and molecular genetic features of a child with COXPD13 and reviewed the relevant literature to improve clinicians’ understanding of the disease and provide a foundation for genetic diagnosis and counseling. We present this article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-419/rc).

Case presentation

The boy was born via normal delivery after a full-term pregnancy, weighing 2,750 grams. Two weeks post-birth, he exhibited slow movements in both upper limbs and the trunk. At 6 months of age, his weight was 4,500 g [−3 standard deviations (SD)], height was 61 cm (−3 SD), and occipitofrontal circumference was 38 cm (−3 SD). He was unable to follow objects with his eyes, smile, or achieve head control. His feeding and sleeping patterns were poor, and he could not sit independently. Neurological assessments indicated motor regression characterized by trunk hypotonia. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed abnormal signal foci in the bilateral white matter, and the electroencephalogram (EEG) showed clinically silent erratic myoclonies, alongside a mildly elevated plasma lactate level.

By 9 months, the patient experienced frequent convulsive seizures, displaying global hypotonia, significant muscle weakness, inability to control his head, and persistent bucofacial dyskinesias. Muscle atrophy led to diminished deep tendon reflexes in the lower limbs. MRI results indicated brain atrophy, and EEG findings showed abnormal brain wave patterns (Figure 1). By 11 months, he was diagnosed with multiple organ damage, white matter changes, epilepsy, muscle tone and strength abnormalities, global developmental delay, growth retardation, and visual and auditory impairment. The seizures, characterized by nodding, flexion of both upper limbs, and clenched fists, began at 9 months, with each episode lasting approximately 3–5 seconds and occurring up to 10 times in succession. Despite the frequency of seizures, the parents declined medication.

At 11 months, the child exhibited developmental delays, including an inability to look up, respond to voice and visual stimuli, and could only babble without acknowledging his name. The Bailey infant growth assessment showed significant motor and cognitive delays, with scores below the 0.1 percentile. His body weight was below −3 SD, and body length fell between −2 and −3 SD. Increased muscle tone was noted in the back, with muscle strength rated at 3–4 in both upper limbs and 0 in both lower limbs. Diagnoses included infantile spasm and severe malnutrition due to low body weight and growth retardation. In patient treatment with adrenocorticotropic hormones proved ineffective, prompting the initiation of oral antiepileptic therapy with levetiracetam and topiramate. An ophthalmic evaluation revealed bilateral optic atrophy. At 39 days old, a brainstem auditory evoked potential test showed an elevated binaural auditory threshold of 50 dB, with no abnormalities noted upon reexamination at 11 months. The child continues to suffer from multiple organ damage, white matter changes, epilepsy, muscle tone and strength abnormalities, global developmental delay, growth retardation, and visual and auditory impairment. Please refer to Figure S1 for the timeline.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval and consent letter

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Approval for this research was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee at Shenzhen Longhua District Maternal and Child Health Hospital (No. 2023083005). Informed consent was provided by the parents of the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Mitochondrial genome sequencing

Two consecutive long-range polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed to specifically amplify the complete mitochondrial genome (10). The resulting amplicons were analyzed using a bioanalyzer to identify any potential deletions in the mitochondrial genome. The amplified fragments were then divided, and adapters compatible with Illumina technology were added to create libraries, which were sequenced on an Illumina platform with an average sequencing depth of approximately 1,000×. The analysis of the raw sequence data involved several steps, including base calling, demultiplexing, alignment to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS) of Human Mitochondrial DNA (NC_012920), and variant identification using validated in-house software. Following base calling and the removal of low-quality reads, a standard bioinformatics process was employed to annotate detected mutations and eliminate potential false positives. This pipeline can accurately detect heteroplasmy levels as low as 15%. All identified variants were carefully evaluated for their potential impact on the patient’s phenotype, except for those classified as benign or likely benign. Relevant variants were included in the final report.

Whole-exome sequencings

A protocol involving salting out was used to extract genomic DNA from the patient’s lymphocytes and from his healthy parents. The DNA concentration of the samples was measured using the Thermo ScientificTM Nanodrop 2000 (Therno Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA), and quality was assessed through agarose gel electrophoresis. Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was performed using the Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) and the Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencing platform (Illumina, San Diego, USA). Subsequent data analysis was conducted with a comprehensive in-house bioinformatics pipeline, encompassing steps such as base calling, read alignment to the GRCh37/hg19 genome assembly, initial filtering of low-quality reads or potential artifacts, and variant annotation. Identified variants were cross-referenced with the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) and the ClinVar database. Variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) below 1% were selected based on data from the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), The Single Nucleotide Polymorphism Database (dbSNP) (build 150), and the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP). Variants were further filtered considering the inheritance pattern, clinical symptoms, neuroimaging, and para-clinical findings to identify potential causative variants.

Variant validation

The primers were designed using the Primer3 Plus database and GeneRunner software. The specificity of the designed primers was assessed through in-silico PCR and the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser. The primers are as follows: forward primers: 5'-tgtaaaacgacggccagtcccttggttgattcccgtag-3'; reversed primers: 5'-caggaaacagctatgaccgacagtgcatacttcaatttcaaca-3'. The identified variant in the affected individual and his healthy parents was then validated via Sanger sequencing using the Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, New York, USA).

Protein modeling prediction

The self-optimized prediction method (SOPMA) database was utilized to predict the secondary structures of both wild-type and variant PNPT1 proteins. The AlphaFold database was employed to assess the impact of the single nonsynonymous variant, c.1033A>G (p.K345E), on the tertiary structure of the protein. Additionally, the missense 3-dimensional (3D) database was specifically designed to predict the tertiary structure of missense variants.

Mitochondrial genome sequencing, WES and Sanger sequencing

Mitochondrial genome sequencing and WES did not reveal any large fragment deletions or duplications in the mitochondrial ring gene or the genomic DNA of the patient. However, WES combined with Sanger sequencing identified a novel homozygous variant, c.1033A>G (p.K345E), in exon 12 of the PNPT1 gene (RefSeq accession number NM_033109.5) located on chromosome 2. This variant results in the substitution of lysine with glutamate, and it was detected in a heterozygous state in both parents (Figure 2). According to guidelines from the American Society of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG), the frequency of this missense variant in the general population database is less than 1 in 1,000,000. While the pathogenicity of this variant has not been documented in current literature, genetic analysis suggests that it may lead to a loss of gene function.

The effect of PNPT1 gene variant on protein structure

Effect of the variant on secondary structure of PNPT1 protein

Based on the SOPMA database, the variant c.1033A>G (p.K345E) in the PNPT1 gene is predicted to cause alterations in various structural elements of the polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase (PNPase) protein, including α helix (Hh), β fold (Ee), β corner (Tt), and random coil (Cc). These changes may affect the secondary structure of the PNPase protein. Notably, the p.K345E variant is located specifically within the α-helix domain (Figures 3,4).

Effect of variant on the tertiary structure of PNPT1 protein

- Based on predictions from AlphaFold modeling and PyMOL mapping analysis, the PNPT1 gene variant c.1033A>G (p.K345E) alters the distance of hydrogen bond formation between LYS345 and ASN341 in the PNPase protein. This change suggests that the variant may impact the backbone structure of the PNPase protein (Table 1 and Figure 5). Consequently, the tertiary structure of PNPase could be affected, potentially leading to reduced stability and impaired protein function.

Table 1

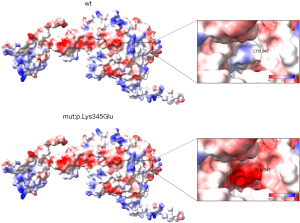

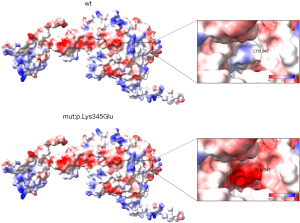

The effect of variant on the tertiary structure of PNPT1 proteinHydrogen bond Distance (A) LYS345 with ASN341 2.9 (WT) LYS345 with ARG349 3.1 (WT) GLU345 and ASN341 3.0 (V) GLU345 with ARG349 3.1 (V) A, angstrom; WT, wild type; V, variant. - The Adaptive Poison-Boltzmann Solver (APBS) in Chimera X predicted a shift in the surface electrostatic potential of the 345th amino acid from electropositive to electronegative due to the variant. Additionally, APBS indicated that the variant also affected the surface electrostatic potential of nearby proteins, highlighting its impact on the surface characteristics of the PNPT1 protein (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Effect of variant on the surface potential of PNPT1 protein. The distribution of positive charge is indicated by blue areas, negative charge by red areas, and areas with no charge by white. Electrostatic effects play a crucial role in protein structure and function. A molecule with a negative surface charge can form bonds with a molecule that has a positive surface charge, and the strength of the binding is determined by the magnitude of the charge. PNPT1, polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 1.

Figure 6 Effect of variant on the surface potential of PNPT1 protein. The distribution of positive charge is indicated by blue areas, negative charge by red areas, and areas with no charge by white. Electrostatic effects play a crucial role in protein structure and function. A molecule with a negative surface charge can form bonds with a molecule that has a positive surface charge, and the strength of the binding is determined by the magnitude of the charge. PNPT1, polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 1. - Prediction of destructive effects of variant on the tertiary structure of PNPT1 protein: according to missense 3D predictions, the variant c.1033A>G (p.K345E) in the PNPT1 gene is anticipated to have destructive effects on the tertiary structure of the PNPT1 protein. This variant may cause significant changes in the overall morphology and volume of the protein (Figure 7), with the substitution of lysine for glutamate resulting in a protein volume expansion of 169.992 A3. These findings suggest that the K345E variant can alter the 3D structure of the protein, potentially impacting its RNA binding and exonuclease activity.

- Protein stability prediction: mutant cutoff scanning matrix (mCSM) and daughters, dudes, mothers, and others fighting cancer together (DUET) were employed to assess the impact of the variant at position 345 in chain A, where lysine is replaced by glutamate. The secondary structure was characterized as cyclic or irregular, with a folding free energy change (ΔΔG) reported as less than 0. Conversely, analysis using SDM online software indicated a stability change with ΔΔG greater than 0 (Figure 8). These findings suggest that the PNPT1 gene variant c.1033A>G (p.K345E) results in the disruption of protein structural stability.

Discussion

In this study, we presented a case of a boy exhibiting multiple organ damage, white matter changes, epilepsy, abnormalities in muscle tone and strength, global developmental delay, growth retardation, and visual and auditory impairment. The patient also showed elevated lactate levels in the plasma. Through WES, we identified a novel heterozygous missense variant in the PNPT1 gene, c.1033A>G (p.K345E), reported for the first time in the Chinese population. This finding suggests a potential diagnosis of COXPD13 according to Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Additionally, bioinformatics analyses indicated that this variant alters the secondary and tertiary structures of the PNPT1 protein, leading to its instability.

COXPD results from impaired OXPHOS function within the mitochondrial respiratory chain (11). COXPDs are primarily caused by variants in various genes that play a role in mitochondrial protein translation, leading to multiple respiratory chain defects. This results in decreased adenosine triphosphate synthesis and affects multiple systems in the human body (12). COXPD13 (MIM: 614932) is classified as an autosomal recessive multisystem disorder associated with mitochondrial dysfunction. Mutations in the PNPT1 gene have been linked to COXPD13, as well as to autosomal recessive deafness (MIM: 614934) and autosomal dominant spinocerebellar ataxia-25 (13,14).

The clinical presentation of COXPD13 is diverse, typically manifesting in infancy with a range of symptoms. To date, 15 cases of COXPD13 have been reported globally, all associated with mutations in the PNPT1 gene (mutation sites summarized in Table 2). Common phenotypic features among these patients include delayed growth, head and neck abnormalities, musculoskeletal issues, and neurological deficits. Additionally, COXPD13 may present with digestive system and ocular abnormalities (6,10,16).

Table 2

| Patient No. | Nucleotide | Amino acids | Reporter | Age (years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | c.1160A>G homozygous | p.Gln387Arg | Vedrenne 2012 (8)/Dhir 2018 (9) | 10 |

| 2 | c.1160A>G homozygous | p.Gln387Arg | Vedrenne 2012 (8) | 3.5 |

| 3 | c.401-1G>A/c.1519G>T heterozygous | p.?/p.Ala 507Ser | Slavotinek 2015 (15) | 1.1 |

| 4 | c.760C>A/c.1528G>C heterozygous | p.Gln254Lys/p.Ala510Pro | Alodaib 2017 (16) | ? |

| 5 | c.760C>A/c.1528G>C heterozygous | p.Gln254Lys/p.Ala510Pro | ? | |

| 6 | c.407G>A homozygous | p.Arg136His | Dhir 2018 (9)/Pennisi 2022 (5) | ? |

| 7 | c.208T>C/c.2137G>T heterozygous | p.Ser70Pro/p.Asp713Tyr | ? | |

| 8 | c.1495G>C/c.1519G>T heterozygous | p.Gly499Arg/p.Ala507Ser | ? | |

| 9 | c.1361C>T/c.1592C>G | p.Thr531Arg/p.Ala454Gly | Rius 2019 (6) | 1.2 |

| 10 | c.1519G>T/c.1519G>T/c.1818T>G | p.Ala507Ser/p.Ala507Ser/p.Val607Lysfs*21 | 3 | |

| 11 | c.1519G>T/c.1592C>G | p.Ala507Ser/p.Thr531Arg | 10 | |

| 12 | c.1519G>T/c.1592C>G | p.Ala507Ser/p.Thr531Arg | ? | |

| 13 | c.1528G>C/c.2212C>T heterozygous | p.Ala510Pro/p.Arg738Cys | Kuht 2021 (7) | 25 |

| 14 | c.1528G>C/c.2212C>T heterozygous | p.Ala510Pro/p.Arg738Cys | 21 | |

| 15 | c.1528G>C/c.2212C>T heterozygous | p.Ala510Pro/p.Arg738Cys | 24 |

?, unknown. PNPT1, polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase 1.

In our study, the patient displayed global developmental delay, truncal hypotonia, hearing impairment, abnormal movements (chorea and dystonia), poor feeding, and epilepsy. Brain MRI revealed hyperintensities in the basal ganglia and white matter atrophy. WES identified a novel heterozygous missense variant in the PNPT1 gene, c.1033A>G (p.K345E). Notably, the patient had elevated plasma lactate levels, indicating OXPHOS dysfunction and increased glycolysis. The observed symptoms aligned with those of COXPD13. However, a limitation of this study is the need for further functional studies to confirm the presence of OXPHOS deficiency in this patient.

The PNPT1 gene is located on chromosome 2p16.1 and consists of 29 exons. It encodes the PNPase protein, which comprises 783 amino acids and plays a crucial role in regulating mitochondrial homeostasis by managing the processing, transport, and degradation of mitochondrial RNA (mt-RNA) (17-19). PNPase is primarily located in the mitochondrial matrix and the intermembrane space (18).

The protein functions as a homologous trimer, forming a tightly bound ring structure. Each subunit contains an N-terminal mitochondrial targeting sequence, two RNase PH (RPH) core domains, and an α-helical PNPase domain (20). The C-terminal portion features two RNA-binding domains: KH and S1 (21). PNPase exhibits in vitro ribonuclease activity, facilitating the processing and degradation of mt-RNA from a 3-primer to a 5-primer (22). It functions as a bifunctional enzyme with both 3' to 5' phospholytic exonuclease activity and 3' terminal oligonucleotide polymerase activity (20).

Trimerization is essential for PNPase’s RNA processing and transport functions, and it also contributes to mitochondrial morphology, respiration, and the maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis (23). Additionally, PNPase offers protection against oxidative stress, although the specific mechanisms remain unclear. Mutations in PNPase can impair RNA binding and degradation activities, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction (23). Abnormalities in mt-RNA processing due to PNPase mutations can result in significant mitochondria deoxyribonucleic acid loss, multiple respiratory chain defects, and impaired OXPHOS, which are critical factors in mitochondrial diseases (24). Furthermore, disruptions in RNA processing can lead to the accumulation of double-stranded mt-RNA in mitochondria, which may leak into the cytoplasm, activating antiviral signaling pathways and triggering a type I interferon response (6,25).

A missense variant occurs when a codon that encodes a specific amino acid is replaced by one that encodes a different amino acid, leading to alterations in the amino acid sequence of a protein. Such variants can significantly impact protein structure and stability, potentially resulting in diminished or lost function, thereby contributing to various diseases. In this study, we investigated the c.1033A>G variant in the PNPT1 gene and its effects on protein structure and function.

The PNPT1 gene encodes the trimeric protein PNPase, which is essential for RNA processing and transport. Previous studies have shown that mutations in PNPT1 can result in unstable monomers, adversely affecting the assembly of the protein complex (7,15,26,27). The c.1033A>G (p.K345E) variant specifically causes the substitution of lysine with glutamate in the α-helix domain.

Using the SOPMA database, AlphaFold modeling, and PyMOL mapping analysis, we predict that this variant may induce significant changes in both the secondary and tertiary structures of the protein. Since lysine 345 is situated at the active site, its replacement by glutamate—a branched-chain amino acid—may disrupt the α-helix structure and compromise the conformation of the active site.

Additionally, APBS and missense 3D analyses indicate that this variant alters the surface electrostatic potential and modifies the hole morphology and volume, resulting in a protein volume expansion of 169.992 A3. Stability predictions from mCSM and DUET confirm that the substitution of lysine with glutamic acid at residue 345 disrupts the overall stability of the PNPT1 protein structure.

These structural changes suggest that the K345E variant could significantly affect the protein’s RNA-binding and exonucleolytic activities. Furthermore, it implies that such mutations not only impair RNA entry into mitochondria but also hinder RNA degradation within these organelles.

In conclusion, the analysis of the secondary and tertiary structure modeling indicates that the missense variant p.K345E in the PNPT1 gene may disrupt the active site, interfere with normal PNPT1 function, and lead to defects in mt-RNA processing, ultimately contributing to the pathophysiology of COXPD13.

Conclusions

The prognosis for COXPD13 is generally unfavorable. In instances where dystonia and dysphagia are observed during the neonatal period or infancy, and particularly when children experience unexplained mortality, it is advisable to conduct genetic testing promptly. This approach can help identify underlying genetic factors, facilitating informed decisions regarding eugenics and family planning.

The complexity of mitochondrial function significantly complicates the accurate diagnosis of mitochondrial diseases. Moreover, the overlapping clinical features of these disorders further hinder effective diagnosis and treatment, necessitating a comprehensive approach to evaluation and management.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank for the technical support of Guangzhou Feitao Gene Testing Company.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-419/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-419/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-419/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committees and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Approval for this research was obtained from the Medical Ethics Committee at Shenzhen Longhua District Maternal and Child Health Hospital (No. 2023083005). Written informed consent for publication was obtained from the parents of the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zhang X, Xiang F, Li D, et al. Adult-onset combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency type 14 manifests as epileptic status: a new phenotype and literature review. BMC Neurol 2024;24:15.

- Webb BD, Nowinski SM, Solmonson A, et al. Recessive pathogenic variants in MCAT cause combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency. Elife 2023;12:e68047.

- Stenton SL, Prokisch H. Genetics of mitochondrial diseases: Identifying mutations to help diagnosis. EBioMedicine 2020;56:102784.

- Nsiah-Sefaa A, McKenzie M. Combined defects in oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid β-oxidation in mitochondrial disease. Biosci Rep 2016;36:e00313.

- Pennisi A, Rötig A, Roux CJ, et al. Heterogeneity of PNPT1 neuroimaging: mitochondriopathy, interferonopathy or both? J Med Genet 2022;59:204-8.

- Rius R, Van Bergen NJ, Compton AG, et al. Clinical Spectrum and Functional Consequences Associated with Bi-Allelic Pathogenic PNPT1 Variants. J Clin Med 2019;8:2020.

- Kuht HJ, Thomas KA, Hisaund M, et al. Ocular Manifestations of PNPT1-Related Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol 2021;41:e293-6.

- Vedrenne V, Gowher A, De Lonlay P, et al. Mutation in PNPT1, which encodes a polyribonucleotide nucleotidyltransferase, impairs RNA import into mitochondria and causes respiratory-chain deficiency. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:912-8.

- Dhir A, Dhir S, Borowski LS, et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA triggers antiviral signalling in humans. Nature 2018;560:238-42.

- Hosseini Bereshneh A, Rezaei Z, Jafarinia E, et al. Crystallographic modeling of the PNPT1:c.1453A>G variant as a cause of mitochondrial dysfunction and autosomal recessive deafness; expanding the neuroimaging and clinical features. Mitochondrion 2021;59:1-7.

- Smith TB, Rea A, Thomas HB, et al. Novel homozygous variants in PRORP expand the genotypic spectrum of combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 54. Eur J Hum Genet 2023;31:1190-4.

- Area-Gomez E, Guardia-Laguarta C, Schon EA, et al. Mitochondria, OxPhos, and neurodegeneration: cells are not just running out of gas. J Clin Invest 2019;129:34-45.

- Smits P, Smeitink J, van den Heuvel L. Mitochondrial translation and beyond: processes implicated in combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiencies. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010;2010:737385.

- Gupta V, Jolly B, Bhoyar RC, et al. Spectrum of rare and common mitochondrial DNA variations from 1029 whole genomes of self-declared healthy individuals from India. Comput Biol Chem 2024;112:108118.

- Slavotinek AM, Garcia ST, Chandratillake G, et al. Exome sequencing in 32 patients with anophthalmia/microphthalmia and developmental eye defects. Clin Genet 2015;88:468-73.

- Alodaib A, Sobreira N, Gold WA, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies novel variants in PNPT1 causing oxidative phosphorylation defects and severe multisystem disease. Eur J Hum Genet 2017;25:79-84.

- Cameron TA, Matz LM, De Lay NR. Polynucleotide phosphorylase: Not merely an RNase but a pivotal post-transcriptional regulator. PLoS Genet 2018;14:e1007654.

- Falchi FA, Pizzoccheri R, Briani F. Activity and Function in Human Cells of the Evolutionary Conserved Exonuclease Polynucleotide Phosphorylase. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:1652.

- Hsu CG, Li W, Sowden M, et al. Pnpt1 mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by MAVS and metabolic reprogramming in macrophages. Cell Mol Immunol 2023;20:131-42.

- Jones GH. Novel Aspects of Polynucleotide Phosphorylase Function in Streptomyces. Antibiotics (Basel) 2018;7:25.

- Khemici V, Linder P. RNA helicases in RNA decay. Biochem Soc Trans 2018;46:163-72.

- Sarkar D, Park ES, Emdad L, et al. Defining the domains of human polynucleotide phosphorylase (hPNPaseOLD-35) mediating cellular senescence. Mol Cell Biol 2005;25:7333-43.

- Smits P, Smeitink JA, van den Heuvel LP, et al. Reconstructing the evolution of the mitochondrial ribosomal proteome. Nucleic Acids Res 2007;35:4686-703.

- Gammage PA, Moraes CT, Minczuk M. Mitochondrial Genome Engineering: The Revolution May Not Be CRISPR-Ized. Trends Genet 2018;34:101-10.

- Wang G, Shimada E, Koehler CM, et al. PNPASE and RNA trafficking into mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1819:998-1007.

- von Ameln S, Wang G, Boulouiz R, et al. A mutation in PNPT1, encoding mitochondrial-RNA-import protein PNPase, causes hereditary hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:919-27.

- Tee WV, Guarnera E, Berezovsky IN. On the Allosteric Effect of nsSNPs and the Emerging Importance of Allosteric Polymorphism. J Mol Biol 2019;431:3933-42.