Clinical, genetic characteristics and long-term follow-up of sitosterolemia in children

Highlight box

Key findings

• Xanthoma is a hallmark clinical manifestation of sitosterolemia in children, with most patients in our cohort harboring mutations in the ABCG5 gene. Genetic testing and serum plant sterol profiling are critical for accurate sitosterolemia diagnosis. Dietary control alone can lead to favorable outcomes in the majority of cases.

What is known and what is new?

• Xanthomas are a common presentation in pediatric sitosterolemia. Most patients have mutations in the ABCG5 gene, and genetic testing along with plant sterol profiling is essential for diagnosis. Both dietary control and treatment with ezetimibe or cholestyramine are effective therapeutic approaches.

• This study enhances the understanding of sitosterolemia by providing a comprehensive analysis of the clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, genetic mutations, and treatment outcomes in 12 pediatric patients. The findings underscore the efficacy of dietary control and adjunctive therapies such as ezetimibe and cholestyramine.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Early diagnosis and timely management of sitosterolemia, including genetic testing and dietary modifications, are pivotal for improving patient outcomes. Increased awareness and routine screening for sitosterolemia, particularly in children presenting with xanthomas, are urgently needed. When dietary control alone is insufficient, ezetimibe and cholestyramine should be considered as adjunctive therapies. Although sitosterolemia remains a rare condition with only a few hundred cases reported globally, this study and previous reports highlight the relative safety and efficacy of ezetimibe. It is recommended that ezetimibe be utilized more actively in cases where dietary interventions fail to achieve adequate control.

Introduction

Sitosterolemia, first described by Bhattacharyya and Connor in 1974 (1), is a rare metabolic disorder characterized by increased absorption and decreased biliary excretion of plant sterols and cholesterol. This leads to markedly elevated serum concentrations of plant sterols, including sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol. Sitosterolemia is an autosomal recessive disorder (1-3) caused by biallelic loss-of-function (LOF) variations (either homozygous or compound heterozygous) in the ABCG5 or ABCG8 genes, which encode adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding cassette (ABC) transporters responsible for sterol excretion from the liver and intestine (4,5).

Clinically, sitosterolemia is often misdiagnosed and managed as familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) due to overlapping presentations (6). Patients with sitosterolemia commonly exhibit tendinous and tuberous xanthomas, as well as premature coronary atherosclerosis. Hematological abnormalities such as macrothrombocytopenia, hemolysis, anemia, and stomatocytosis have also been reported in these patients (7). Notably, these hematological features are also seen in patients with FH, further complicating diagnosis (8,9). While only a few hundred cases of sitosterolemia have been documented to date, it is increasingly recognized that the condition may be significantly underdiagnosed. A rough estimates that the incidence rate of sitosterolemia is 1 in 200,000. Recent studies suggest that the actual prevalence of sitosterolemia may be higher than previously thought (10,11). In this study, we provide a comprehensive analysis of 12 pediatric patients diagnosed with sitosterolemia. We summarize their clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, genetic variations, and treatment responses. Additionally, we report longitudinal follow-up data spanning over 8 years, offering valuable insights into the long-term management of this rare disorder. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-457/rc).

Methods

We studied 12 pediatric patients in our center with sitosterolemia, all of whom met the following criteria (Table S1). During the diagnostic process, it was determined that, despite the absence of a genetic abnormality being identified in patient 8 (P8), the clinical diagnostic criteria were nevertheless met (fulfills A-1, B-1, and C in Table S1). The data collected included clinical signs and symptoms at presentation, age at diagnosis, baseline laboratory findings, family history, clinical manifestations, laboratory findings at the most recent follow-up (from January 2015 to January 2024), treatment protocols, and genetic test results (ABCG5 and/or ABCG8).

Laboratory assessments included blood lipid profiles [reference ranges: total cholesterol (TC), 0–5.7 mmol/L; low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), 1.25–3.3 mmol/L], alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels (reference range: 0–40 U/L), plasma sterol analysis (reference ranges: cholestanol, 0.01–10 µmol/L; sitosterol, 1.00–15.00 µmol/L; stigmasterol, 0.10–8.50 µmol/L; campesterol, 0.01–10.00 µmol/L), and complete blood counts (reference range: hemoglobin, 110–150 g/L; mild anemia, 90 g/L ≤ hemoglobin <110 g/L; moderate anemia, 60 g/L ≤ hemoglobin <90 g/L). Cardiovascular and carotid artery ultrasounds were also performed. Serum sitosterol levels were measured using a gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyzer (QP2010 Plus, Shimadzu, Japan). All genetic testing was conducted with informed consent. This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of The Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics (approval number: SHERLLM2024016). Informed consent was waived for this study due to the exclusive use of de-identified patient data, which posed no potential harm or impact on patient care. This waiver was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of The Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics in accordance with regulatory and ethical guidelines pertaining to retrospective studies. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Among the 12 patients, 10 were unrelated, while two were siblings (an older sister and her younger brother). Importantly, no instances of consanguineous marriage were reported among their parents, and none of the patients had a notable family history. Genetic testing was performed on all patients and their parents, while sterol testing was conducted in nine patients.

Following diagnosis, patients 1–7, 9, and 11 (P1–7, P9, and P11) were managed with a low-plant sterol diet. P8 was treated with ezetimibe (5 mg/day) in combination with cholestyramine (2 g twice daily) for 12 months. Patient 10 (P10) received ezetimibe at a dose of 2.5 mg/day for 24 months, while patient 12 (P12) was treated with ezetimibe at a dose of 5 mg/day for 6 months. After the treatment periods, the patients’ blood lipid profiles were re-evaluated. The duration of treatment across all patients ranged from 1 to 8 years.

Results

We recruited 12 pediatric patients with sitosterolemia, comprising five boys and seven girls. Among them, patient 2 (P2; older sister) and patient 3 (P3; younger brother) belonged to the same family, while the remaining patients came from 11 non-consanguineous families. The median age at diagnosis was 1.2 years (range: 4 months to 8 years and 3 months).

The initial symptoms varied among the patients. Xanthomas were the most common presentation, observed in 58% of patients. These xanthomas were frequently located at the knee joints, elbow joints, Achilles tendons, and gluteal folds. Elevated lipid levels were incidentally detected in 5 patients (42%). All 12 patients exhibited elevated TC (range: 7.33–76.92 mmol/L) and LDL-C (range: 4.54–74.37 mmol/L). Among the nine patients who underwent serum phytosterol testing, all demonstrated markedly increased levels of sitosterol, supporting the diagnosis of sitosterolemia. Other elevated sterols included cholestanol (range: 5.53–82.52 µmol/L), sitosterol (range: 13.64–231.69 µmol/L), stigmasterol (range: 0.73–13.13 µmol/L), and campesterol (range: 20.35–170.20 µmol/L).

Hematological abnormalities constituted the second most common manifestation, occurring in 5 patients (42%) with mild anemia (hemoglobin 92–109 g/L). Additionally, 1 patient (8%) exhibited carotid artery intima roughness. Notably, no cases of severe anemia, stomatocytes, thrombocytopenia, megathrombocytes, arthralgia, or cardiovascular damage were observed.

Genetic testing was conducted for all patients. Pathogenic variants in the ABCG5 gene were identified in 10 patients (83%), while 1 patient (8%) harbored pathogenic variants in the ABCG8 gene. No genetic variants were detected in 1 patient (P8, 8%) (Table 1). However, P8 exhibited pronounced clinical features, including visible xanthomas, significantly elevated LDL-C and TC levels, and increased serum phytosterols. The patient responded well to treatment with ezetimibe and cholestyramine, meeting the diagnostic criteria for sitosterolemia (Figure 1).

Table 1

| Characteristics (reference ranges) | P1 | P2 (older sister) | P3 (younger brother) | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 | P11 | P12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | M | F | M | F | F | F | F | M | M | F | F | M |

| Diagnosis age | 10m | 8y3m | 4y2m | 1y1m | 10m | 6y4m | 1y2m | 5y1m | 7y2m | 1y | 4m | 7y |

| Xanthomas | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | + |

| ALT (0–40 U/L) | 12.4 | 13.2 | 20 | 11.3 | 10 | 30 | 16.8 | 213.1 | 28 | 23.4 | 15.6 | 16.2 |

| AST (0–40 U/L) | 33.6 | 31 | 25 | 27.1 | 34.6 | 12 | 26.1 | 245.4 | 24 | 47.5 | 40.1 | 25 |

| TC (0–5.7 mmol/L) | 18.45 | 15.42 | 7.33 | 25.05 | 26.03 | 7.36 | 20.02 | 76.92 | 9.81 | 22.1 | 7.85 | 10.5 |

| LDL-C (1.25–3.3 mmol/L) | 15.99 | 13.49 | 5.88 | 17.67 | 20.45 | 4.54 | 15.2 | 74.37 | 8.68 | 16.39 | 5.56 | 9.25 |

| Total triglycerides (0–1.69 mmol/L) | 0.71 | 1.18 | 1.2 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 0.61 | 1.7 | 1.84 | 0.96 | 0.9 | 0.94 | 0.49 |

| Blood count | Normal | Normal | Normal | Mild anemia | Mild anemia | Mild anemia | Normal | Mild anemia | Normal | Normal | Normal | Mild anemia |

| Serum sitosterol | ||||||||||||

| Squalene (0.3–4 μmol/L) | / | 0.41 | 0.38 | 3.69 | / | 0.48 | 0.61 | 3.46 | / | 0.69 | 0.6 | 2.38 |

| Cholestanol (0.01–10 μmol/L) | / | 82.52 | 48.5 | 21.58 | / | 5.53 | 35.89 | 24.93 | / | 12.46 | 10 | 13.62 |

| Desmosterol (0.3–5 μmol/L) | / | 3.31 | 3.4 | 4.24 | / | 1.95 | 6.91 | 2.13 | / | 2.62 | 2.57 | 0.73 |

| Lathosterol (0.01–12.5 μmol/L) | / | 0.68 | 1.03 | 0.35 | / | 0.71 | 3.2 | 0.93 | / | 1.48 | 0.82 | 0.13 |

| Campesterol (0.01–10 μmol/L) | / | 170.2 | 154.74 | 78.5 | / | 23.29 | 138.45 | 138.88 | / | 59.76 | 20.35 | 122.29 |

| Stigmasterol (0.1–8.5 μmol/L) | / | 11.62 | 8.62 | 9.92 | / | 0.82 | 12.19 | 13.13 | / | 3.95 | 0.73 | 17.02 |

| Sitosterol (1–15 μmol/L) | / | 231.69 | 212.29 | 84.76 | / | 14.94 | 121.15 | 80.45 | / | 56.7 | 13.64 | 169.3 |

| Therapy | a | a | a | a | a | a | a | a + b + c | a | a + b | a | a + b |

| Follow-up period | 6y7m | 1y7m | 1y7m | 1y4m | 8y7m | 1y1m | 1y5m | 1y7m | 3y | 5y | 2y11m | 3y |

| TC after therapy (0–5.7 mmol/L) | 6.27 | 7.07 | 5.89 | 4.7 | 6.61 | 5.33 | 7.22 | 16.63 | 5.23 | 4.71 | 6.42 | 5.95 |

| LDL-C after therapy (1.25–3.3 mmol/L) | 5.24 | 4.94 | 3.87 | 4.03 | 4.92 | 3.11 | 5.62 | 8.74 | 3.71 | 2.22 | 4.49 | 4.52 |

| Gene mutations | ABCG8 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | Negative | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 | ABCG5 |

| c.480C> A(p.N160K) |

c.1762+1G> A(p.?) |

c.1762+1G> A(p.?) |

c.831_849dup (p.F284Sfster5) |

c.751G> A(p.Q251X) |

c.1337G> A(p.R446Q) |

c.904+1G> A(p.?) |

/ | c.904+1G> A(p.?) |

c.1337G> A(p.R446Q) |

c.281C> G(p.T94R) |

c.1336C> T(p.R446X) |

|

| c.789delG (p.L264Wfs*22) |

c.1337G> A(p.R446Q) |

c.1337G> A(p.R446Q) |

c.1166G> A(R389H) |

c.1336C> T(p.R446X) |

c.1337G> A(p.R446Q) |

c.-76C> T(p.?) |

/ | c.1336C> T(p.R446X) |

c.1336C> T(p.R446X) |

c.1864A> C(p.M622V) |

c.1336C> T(p.R446X) |

+, positive; −, negative; /, no data; a, phytosterol-limited diet; b, ezetimibe; c, cholestyramine. ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; F, female; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; M, male; m, months; P, patient; TC, total cholesterol; y, years.

The first-line treatment for all patients was a diet low in xenosterols and cholesterol. High-phytosterol foods, including vegetable oil, chocolate, nuts, shellfish, and soy products, were strictly restricted. Nine patients were managed with a low-cholesterol and low-phytosterol diet alone. Among these, three patients were initially misdiagnosed with FH and treated with atorvastatin for a period before the correct diagnosis was established. Upon confirmation of sitosterolemia, atorvastatin was discontinued, and dietary therapy was implemented exclusively (Figure 2).

Three patients received combination therapy with ezetimibe and/or cholestyramine due to insufficient response to dietary intervention alone. The details are as follows: P8 transitioned to combination therapy with ezetimibe (5 mg/day) and cholestyramine (2 g twice daily) for 12 months due to unsatisfactory results from dietary therapy alone. Patient 10 (P10) was treated with ezetimibe (2.5 mg/day) for 24 months. Patient 12 (P12) was treated with ezetimibe (5 mg/day) for 6 months.

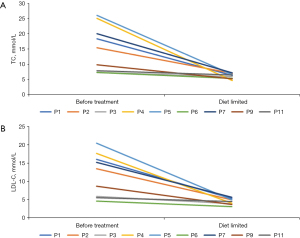

At the end of the long-term follow-up period (1 year 1 month to 8 years 7 months) (Figure 3), all patients showed significant improvements in TC and LDL-C levels, as well as in clinical signs and symptoms. Three patients (P1, P5, P10) achieved complete resolution of their xanthomas within 1 to 2 years of treatment. The remaining four patients experienced substantial reductions in the size or number of their xanthomas (P4, P8, P9, P12) (Figure 4). Of note, five patients exhibited normal hemoglobin levels, indicating the resolution of mild anemia observed at baseline.

Discussion

The clinical and biochemical characteristics, serum sitosterol levels, genetic variants, and follow-up data of 12 patients with sitosterolemia were analyzed in this study. The patients exhibited significant heterogeneity in clinical manifestations, ranging from no specific symptoms to the presence of xanthomas. Previous reports have identified xanthomas as the most common symptom and initial presentation in pediatric patients, with a prevalence of 73.1–100% (11-16). Consistent with these findings, our study observed that 58% of patients presented with xanthomas, with the onset as early as the fourth month of life. The xanthomas were primarily localized to the wrists and knees.

Hematological disorders are the second most common clinical feature, with a prevalence of 22–39% in previous reports. These include significant hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and splenomegaly (17). In our cohort, 42% of patients exhibited hematological abnormalities, all of which were mild anemia. No cases of thrombocytopenia, stomatocytes, or megathrombocytes were observed. Some studies have reported atherosclerosis in 10% of pediatric cases, with onset as early as 7.1 years of age. Other complications, such as arthralgia and splenomegaly, are also reported in nearly 10% of pediatric patients (18-23). However, in our study, only one patient exhibited carotid artery intima roughness, and no cardiovascular complications, arthralgia, or splenomegaly were observed.

A research has suggested that blood lipid levels may serve as a predictive factor for the age and location of xanthoma occurrence (11). Sitosterolemia is frequently misdiagnosed and mistreated as FH, presenting a significant challenge in clinical practice. Three of our patients were misdiagnosed with FH and initially treated with atorvastatin, but the treatment was ineffective.

To date, sitosterolemia has been reported in only a few hundred cases and is considered an extremely rare disorder. No accurate morbidity data are currently available, though approximately 200 cases have been documented worldwide. The Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) Exome Browser, a public genetic database, has estimated that 1 in 220 individuals in the general population carries variants in the ABCG5 or ABCG8 genes. Based on these data, the estimated prevalence of homozygous or compound heterozygous patients with sitosterolemia is approximately 1 in 200,000 individuals (10,24). However, recent studies suggest that the condition may be far more prevalent than previously thought (11).

All patients responded favorably to dietary therapy, with TC and LDL-C levels decreasing satisfactorily in nine patients. However, three patients were dissatisfied with the extent of the decrease and initiated combination therapy with ezetimibe. The addition of ezetimibe demonstrated significant efficacy in further reducing blood lipid levels. During long-term follow-up, 11 patients achieved satisfactory blood lipid control, maintaining levels near the normal range. One patient continued to exhibit elevated lipid levels, although LDL-C decreased by nearly 90%. The therapeutic effect was evident not only in laboratory results but also in clinical manifestations. Xanthomas disappeared completely in three patients, while the remaining four patients experienced substantial reductions in the size or number of their xanthomas during follow-up. Xia et al. reported that in a cohort of 20 pediatric patients, TC and LDL-C levels decreased by 67% and 75%, respectively, with dietary therapy alone. Among these, 55% of patients achieved lipid levels within the normal range. The addition of ezetimibe resulted in further reductions of 18% and 20% in TC and LDL-C levels, respectively, accompanied by symptomatic relief or even complete resolution of clinical signs (11). Therefore, a low-plant-sterol diet forms the cornerstone of sitosterolemia treatment.

Several studies have demonstrated that ezetimibe significantly reduces plasma phytosterol levels (12,13). However, ezetimibe has not been routinely recommended for patients under 10 years of age due to potential adverse effects, including arthralgia (11). In our study, three patients under the age of 10 years tolerated ezetimibe without any observed side effects. These findings suggest that ezetimibe is an effective treatment option for sitosterolemia in young patients, but its use requires careful monitoring, particularly in children younger than 10 years old, to promptly identify and manage potential adverse effects.

Most Chinese or Asian patients with sitosterolemia have variations in the ABCG5 gene, whereas Caucasian patients predominantly exhibit variations in the ABCG8 gene (11-16,25). In our study, ABCG5 and ABCG8 variants accounted for 91% and 9% of cases, respectively, aligning with previous findings. Xia et al. [2022] reported that among 55 patients, 76% had ABCG5 variants, while 24% had ABCG8 variants (11). Similarly, Zhou et al. [2022] summarized 54 patients and found that 71% exhibited ABCG5 variations, compared to 27% with ABCG8 variations (13).

Certain mutations appear to be hot-spot variations among Chinese patients, including R446X, Q251X, and R389H (11-15). In our cohort, common pathogenic variations in the ABCG5 gene included c.1337G>A/p.R446Q, c.1336C>T/p.R446X, and F.c.904+1G>A. Notably, although genetic testing failed to identify pathogenic variants in one patient, their markedly elevated lipid levels, clinical presentation, and phytosterol profile met the diagnostic criteria for sitosterolemia. Treatment with a low-phytosterol diet, combined with cholestyramine and ezetimibe, yielded favorable therapeutic outcomes for this patient.

Conclusions

In summary, this study comprehensively described 12 pediatric patients with sitosterolemia, highlighting their clinical, biochemical, genetic, therapeutic, and follow-up characteristics. A low-phytosterol diet was proved to be an effective first-line treatment for sitosterolemia, achieving significant improvements in blood lipid levels and clinical symptoms. Furthermore, ezetimibe was shown to be an effective and relatively safe adjunctive treatment. However, adverse effects, particularly in very young children, require vigilant monitoring to ensure patient safety.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-457/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-457/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-457/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-457/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of The Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics (approval number: SHERLLM2024016). Informed consent was waived for this study due to the exclusive use of de-identified patient data, which posed no potential harm or impact on patient care. This waiver was approved by the institutional research ethics committee of The Children’s Hospital Capital Institute of Pediatrics in accordance with regulatory and ethical guidelines pertaining to retrospective studies. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bhattacharyya AK, Connor WE. Beta-sitosterolemia and xanthomatosis. A newly described lipid storage disease in two sisters. J Clin Invest 1974;53:1033-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salen G, Shefer S, Nguyen L, et al. Sitosterolemia. J Lipid Res 1992;33:945-55.

- Tada H, Nomura A, Ogura M, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Sitosterolemia 2021. J Atheroscler Thromb 2021;28:791-801. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, et al. Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat Genet 2001;27:79-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bydlowski SP, Levy D. Association of ABCG5 and ABCG8 Transporters with Sitosterolemia. Adv Exp Med Biol 2024;1440:31-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tada MT, Rocha VZ, Lima IR, et al. Screening of ABCG5 and ABCG8 Genes for Sitosterolemia in a Familial Hypercholesterolemia Cascade Screening Program. Circ Genom Precis Med 2022;15:e003390. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bastida JM, Benito R, Janusz K, et al. Two novel variants of the ABCG5 gene cause xanthelasmas and macrothrombocytopenia: a brief review of hematologic abnormalities of sitosterolemia. J Thromb Haemost 2017;15:1859-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakuma N, Tada H, Mabuchi H, et al. Lipoprotein Apheresis for Sitosterolemia. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:896-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawamura R, Saiki H, Tada H, et al. Acute myocardial infarction in a 25-year-old woman with sitosterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 2018;12:246-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tada H, Okada H, Nomura A, et al. Rare and Deleterious Mutations in ABCG5/ABCG8 Genes Contribute to Mimicking and Worsening of Familial Hypercholesterolemia Phenotype. Circ J 2019;83:1917-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xia Y, Duan Y, Zheng W, et al. Clinical, genetic profile and therapy evaluation of 55 children and 5 adults with sitosterolemia. J Clin Lipidol 2022;16:40-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tada H, Kojima N, Yamagami K, et al. Clinical and genetic features of sitosterolemia in Japan. Clin Chim Acta 2022;530:39-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou Z, Su X, Cai Y, et al. Features of chinese patients with sitosterolemia. Lipids Health Dis 2022;21:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu L, Wen W, Yang Y, et al. Features of Sitosterolemia in Children. Am J Cardiol 2020;125:1312-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gu R, Wang H, Wang CL, et al. Gene variants and clinical characteristics of children with sitosterolemia. Lipids Health Dis 2024;23:83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rocha VZ, Tada MT, Chacra APM, et al. Update on Sitosterolemia and Atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep 2023;25:181-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Del Castillo J, Tool ATJ, van Leeuwen K, et al. Platelet proteomic profiling in sitosterolemia suggests thrombocytopenia is driven by lipid disorder and not platelet aberrations. Blood Adv 2024;8:2466-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tada H, Kawashiri MA, Okada H, et al. A Rare Coincidence of Sitosterolemia and Familial Mediterranean Fever Identified by Whole Exome Sequencing. J Atheroscler Thromb 2016;23:884-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamada Y, Sugi K, Gatate Y, et al. Premature Acute Myocardial Infarction in a Young Patient With Sitosterolemia. CJC Open 2021;3:1085-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iyama K, Ikeda S, Koga S, et al. Acute Coronary Syndrome Developed in a 17-year-old Boy with Sitosterolemia Comorbid with Takayasu Arteritis: A Rare Case Report and Review of the Literature. Intern Med 2022;61:1169-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoo EG. Sitosterolemia: a review and update of pathophysiology, clinical spectrum, diagnosis, and management. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2016;21:7-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Desai SR, Korula A, Kulkarni UP, et al. Sitosterolemia: Four Cases of an Uncommon Cause of Hemolytic Anemia (Mediterranean Stomatocytosis with Macrothrombocytopenia). Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2021;37:157-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao LJ, Yu ZJ, Jiang M, et al. Clinical features of 20 patients with phytosterolemia causing hematologic abnormalities. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2019;99:1226-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016;536:285-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kojima N, Tada H, Nomura A, et al. Putative Pathogenic Variants of ABCG5 and ABCG8 of Sitosterolemia in Patients With Hyper-Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterolemia. J Lipid Atheroscler 2024;13:53-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]