Non-invasive brain stimulation for upper extremity dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Highlight box

Key findings

• A meta-analysis was conducted on safety and effectiveness of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) in upper extremity dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy (CP).

What is known and what is new?

• NIBS is an emerging technique which mainly uses electric current or magnetic field to regulate the excitability of relevant functional areas of the brain, causing immediate and prolonged modulation of cortex excitability. In clinical setting, NIBS has been used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, adult stroke, autism, CP, and so on.

• NIBS is safe and well tolerated in improving upper extremity function in CP children. And tDCS is effective in improving upper extremity function and spasticity in CP children.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• NIBS, especially tDCS, may be used as an adjunct for the clinical rehabilitation of children with CP.

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a group of persistent disorders affecting the development of movement and posture (1-3). In addition to motor dysfunction, children with CP often have sensory, perceptual, cognitive, as well as epilepsy and secondary musculoskeletal problems (3,4). CP is the leading cause of disability in children (5,6), with an incidence that approximately ranged from 0.8 and 4.4 per 1,000 newborns (7). Approximately 83% of children with CP suffer from upper extremity dysfunction (8), which significantly impacts their daily activity and quality of life (9), and increases the burden on their caregivers and society (10).

Rehabilitation interventions for upper extremity dysfunction in CP mainly aim to improve extremity function and abnormal posture, promote self-care, and reduce the risk of disability. At present, there are two types of common rehabilitation techniques, with one mainly focusing on the clinical symptoms of CP, improving the function of peripheral organs, regulating the central nervous system indirectly, including constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) (11), hand-arm bimanual intensive training (HABIT) (12), virtual reality (VR), and computer-based training (13), mirror therapy (14,15) and so on. And another directly acts on the cerebral cortex, promoting neural plasticity, and improving the clinical symptoms from the center to the periphery, including invasive and non-invasive techniques such as non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS).

NIBS is an emerging technique which mainly uses electric current or magnetic field to regulate the excitability of relevant functional areas of the brain, causing immediate and prolonged modulation of cortex excitability (16). And neural plasticity is the primary mechanism of NIBS for improving dysfunction (17). Preclinical animal studies have shown that rTMS promoted long-term synaptic enhancement, neuroprotection, and neurogenesis (18), and tDCS regulated neurogenesis, increased oligodendrocyte precursor recruitment, and polarize microglia (19). In clinical setting, NIBS has been used in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (20), adult stroke (21), autism (22), CP, and so on.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) are the most commonly used NIBS techniques. rTMS treats diseases through the principle of electromagnetic induction (16). A current passes through a coil placed on the skull, creating a magnetic field perpendicular to the coil, which generates an electric current parallel to the coil in the cortex, and regulates the excitability of local brain regions (23,24). tDCS, on the other hand, uses low-amplitude direct current (1–2 mA) to modify neuronal polarization, altering transmembrane electrical potentials to regulate the excitability of local brain regions, by applying a low-amplitude direct current (1–2 mA) through sponge electrodes positioned on the scalp (25,26). In randomized controlled trials (RCTs), the control group is generally treated with sham stimulation. Generally speaking, sham rTMS stimulation mimic the sound and tactile sensation of rTMS by using a sham rTMS coil without stimulation; another sham rTMS is that A therapist orientated the handle pointing at a 90° angle to the sagittal line (a 45° angle for the real rTMS). And sham tDCS is a procedure that applies current 30 seconds to 1 minute after the start and before the end of tDCS. This is mainly to allow participants to experience the current sensation at the beginning and end of tDCS, but does not actually provide long-term current stimulation.

However, the safety and effectiveness of NIBS for upper extremity dysfunction in children with CP is unclear, with only few articles having ever addressed the problem. In 2024, Metelski et al. (27) reported a systematic review of NIBS improving upper extremity function, and the databases were searched up to May 2023, which was classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), descriptive analyses of adverse events, feasibility and efficacy were conducted. The article was only systematically reviewed, and no meta-analysis was performed, which imposed methodological limitations. There were few statistically significant improvements in results for efficacy. Our study conducted meta-analysis by integrating the same outcome measures, and analyzed tolerability and safety using the number of dropouts and adverse events. The effectiveness and safety of NIBS were quantitatively analyzed, with based meta-analysis based on RCT provided the highest level of evidence. And compared with systematic reviews, meta-analyses were methodologically able to increase statistical power and accuracy in estimating effect sizes, and to enhance the reliability and objectivity of the results.

In clinical practice, there are no standard parameters of stimulation such as intensity, frequency, site of stimulation determined yet. These parameters are associated with clinical outcomes and safety to some extent (26,28-32). NIBS targets specific localized different brain regions and is non-invasive, thus it is important to understand the feasibility and safety of NIBS in the treatment of upper extremity dysfunction in children with CP. As a promising rehabilitation technique for neurological disorders, impact of NIBS for upper extremity dysfunction in children with CP remains to be further studied. Therefore, this study aims to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing studies to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of NIBS for upper extremity dysfunction in children with CP. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-488/rc) (33).

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered in PROSPERO with registration number CRD42023411971.

Search strategy

Two reviewers (Y.Z. and M.Z.) conducted the systematic review search on June 2024. Five databases were searched including PubMed, Web of Science, ProQuest, Scopus, and Embase. Keywords were used in search terms including “cerebral palsy”, “perinatal stroke”, “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation”, “transcranial direct current stimulation”, “non-invasive brain stimulation”, “upper extremity”, “hand”, and their synonyms. The keywords matched the appropriate medical subject headings (MeSH) terms. Relevant truncation or wildcard symbols were used to cover all possible variations of keywords. Related search terms were combined with Boolean operators. The terms were adjusted to fit the requirements of each electronic database. Table 1 shows the search strategy used in each database.

Table 1

| Databases | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((“Cerebral palsy”[MeSH Terms] OR “Cerebral palsy”[All Fields] OR “CP”[All Fields] OR “perinatal stroke”[All Fields] OR “hemiplegi*”[All Fields] OR “monoplegi*”[All Fields] OR “diplegi*”[All Fields] OR “triplegi*”[All Fields] OR “quadriplegi*”[All Fields] OR “tetraplegi*”[All Fields]) AND (“transcranial magnetic stimulation”[MeSH Terms] OR “TMS”[All Fields] OR “transcranial magnetic stimulation*”[All Fields] OR “rTMS”[All Fields] OR “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation*”[All Fields] OR “deep transcranial magnetic stimulation”[All Fields] OR (“transcranial direct current stimulation”[MeSH Terms] OR “tDCS”[All Fields] OR “transcranial direct current stimulation*”[All Fields]) OR (“NIBS”[All Fields] OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*”[All Fields] OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*”[All Fields])) AND (“hand function”[All Fields] OR “hand*”[All Fields] OR “upper extremity”[MeSH Terms] OR “upper extremity*”[All Fields] OR “upper limb*”[All Fields] OR “arm”[All Fields])) AND ((english[Filter]) AND (allchild[Filter])) |

| Web of Science | (“cerebral palsy” OR “CP” OR “perinatal stroke” OR “hemiplegi*” OR “monoplegi*” OR “diplegi*” OR “triplegi*” OR “quadriplegi*” OR “tetraplegi*”) AND (“child” OR “children” OR “kid*” OR “neonate” OR “infant*”) AND ((“TMS” OR “transcranial magnetic stimulation*” OR “rTMS” OR “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation*” OR “deep transcranial magnetic stimulation”) OR (“tDCS” OR “transcranial direct current stimulation*”) OR (“NIBS” OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*” OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*”)) AND (“hand function” OR “hand*” OR “upper extremity*” OR “upper limb*” OR “arm*”) (Topic) and English (Languages) |

| Embase | (‘cerebral palsy’/exp OR ‘cerebral palsy’ OR ‘cp’/exp OR ‘cp’ OR ‘hemiplegi*’ OR ‘monoplegi*’ OR ‘diplegi*’ OR ‘triplegi*’ OR ‘quadriplegi*’ OR ‘tetraplegi*’) AND (‘transcranial magnetic stimulation’/exp OR ‘tms’ OR ‘transcranial magnetic stimulation*’ OR ‘rtms’ OR ‘repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation*’ OR ‘deep transcranial magnetic stimulation’ OR ‘tdcs’ OR ‘transcranial direct current stimulation*’ OR ‘nibs’ OR ‘non-invasive brain stimulation*’ OR ‘transcranial direct current stimulation’/exp) AND (‘hand function’ OR ‘hand’ OR ‘upper extremity’/exp OR ‘upper extemity*’ OR ‘upper limb*’ OR ‘arm*’) AND [article]/lim AND [humans]/lim AND [english]/lim AND ([newborn]/lim OR [infant]/lim OR [child]/lim OR [preschool]/lim OR [school]/lim OR [adolescent]/lim) |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“cerebral palsy” OR “CP” OR “perinatal stroke” OR “hemiplegi*” OR “monoplegi*” OR “diplegi*” OR “triplegi*” OR “quadriplegi*” OR “tetraplegi*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“TMS” OR “transcranial magnetic stimulation*” OR “rTMS” OR “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation*” OR “deep transcranial magnetic stimulation” OR “tDCS” OR “transcranial direct current stimulation*” OR “NIBS” OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*” OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“hand function” OR “hand*” OR “upper extremity*” OR “upper limb*” OR “arm*”) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY(“stroke” OR “apoplexy” OR “autism” OR “ASDs”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“child” OR “children” OR “kid*” OR “neonate” OR “infant*”) AND NOT TITLE-ABS-KEY(“adult*” OR “mice” OR “mouse”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE, “final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, “ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, “English”)) |

| ProQuest | (((“cerebral palsy” OR “CP” OR “perinatal stroke” OR “hemiplegi*” OR “monoplegi*” OR “diplegi*” OR “triplegi*” OR “quadriplegi*” OR “tetraplegi*”) NOT (“stroke” OR “apoplexy” OR “autism” OR “ASDs”)) AND ((“child” OR “children” OR “kid*” OR “neonate” OR “infant*”) NOT (“adult*” OR “mice” OR “mouse”)) AND ((“TMS” OR “transcranial magnetic stimulation*” OR “rTMS” OR “repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation*” OR “deep transcranial magnetic stimulation”) OR (“tDCS” OR “transcranial direct current stimulation*” NOT (“FES” OR “functional electrical stimulation”)) OR (“NIBS” OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*” OR “non-invasive brain stimulation*”)) AND (“hand function” OR “hand*” OR (“upper extremity”) OR (“upper limb” OR “upper limbs”) OR “arm*”)) AND (stype.exact(“Scholarly Journals” OR “Dissertations & Theses”) AND la.exact(“ENG”)) |

ASDs, autism spectrum disorders; CP, cerebral palsy; FES, functional electrical stimulation; MeSH, medical subject headings; NIBS, non-invasive brain stimulation; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were set following the PICOS (population, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, and study design) principle, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2

| Subject | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| P-population | Children diagnosed with CP who aged 18 years old or younger | Animal or non-human experiments |

| Children were diagnosed with genetic or chromosomal disorders or congenital neurological illness | ||

| I-intervention | NIBS, including tDCS or rTMS | Studies using NIBS as diagnostic means |

| C-comparison | Between-group comparison and/or within group comparison and/or pre-post comparison | N/A |

| Intervention group and control group comparison | ||

| O-outcomes | Measures outcomes related to upper limb function performance including the AHA, the COPM, BBT, MAS, HGS, MA, and ABILHAND-Kids | N/A |

| S-study type | RCTs | Any articles that do not have full-text available |

| Non-English studies |

AHA, Assisting Hand Assessment; BBT, Box and Block Test; COPM, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; CP, cerebral palsy; HGS, Hand Grip Strength; MA, Melbourne Assessment; MAS, Modified Ashworth Scale; NIBS, non-invasive brain stimulation; N/A, not available; PICOS, population, intervention, comparisons, outcomes, and study design; RCT, randomized controlled trial; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

The inclusion criteria were: (I) children diagnosed with CP who aged 18 years old or younger; (II) the intervention focus on NIBS including rTMS and tDCS; (III) between-group comparison, within-group comparison, pre-post comparison, and intervention group and control group comparison (including comparisons between the active and sham stimulation); (IV) measures outcomes related to upper extremity function performance including the Assisting Hand Assessment (AHA), the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM), Box and Block Test (BBT), Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS), Hand Grip Strength (HGS), Melbourne Assessment (MA), and ABILHAND-Kids; and (V) RCTs.

The exclusion criteria were: (I) animal or non-human experiments, and children diagnosed with genetic or chromosomal disorders or congenital neurological illness were excluded; (II) any articles not having full-text available or non-English studies were excluded; and (III) studies using NIBS as diagnostic means were excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

Study selection and data extraction were conducted independently by two reviewers (Y.Z. and M.Z.), and any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion with the third person (K.X.) in the team. We first evaluated the retrieved studies based on the titles and abstracts of the literature, followed by full-text analyses and evaluation of all eligible studies to assess their compliance with the eligibility criteria. The following data were extracted: title, authors, publication year, study design, participants characteristics [sample size, age, type of CP, manual ability classification system (MACS) level], adverse events, stimulation parameters (intensity and frequency), stimulation site, duration, number of sessions, outcome measures, assessment time points (the time intervals from treatment to evaluation) and main conclusion, etc. Some RCTs provide raw data that can be obtained directly or calculated to derive mean and standard deviation, for data presented in graphs, WebPlotDigitizer version 3.10 was used to obtain data manually. Where necessary, the standard deviation was calculated from the mean standard by means of Cochrane handbooks and formulas.

Quality assessment

This study assessed the methodological quality of included studies using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale: https://pedro.org.au/english/resources/pedro-scale/. The PEDro scale is a valid and reliable measure of methodological quality of clinical trials (34). It contains eleven questions for scoring: (I) eligibility criteria were specified; (II) subjects were randomly allocated to groups; (III) allocation was concealed; (IV) the groups were similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators; (V) there was blinding of all subjects; (VI) there was blinding of all therapists who administered the therapy; (VII) there was blinding of all assessors who measured at least one key outcome; (VIII) measures of at least one key outcome were obtained from more than 85% of the subjects initially allocated to groups; (IX) all subjects for whom outcome measures were available received the treatment or control condition as allocated or, where this was not the case, data for at least one key outcome was analyzed by “intention to treat”; (X) the results of between-group statistical comparisons are reported for at least one key outcome; and (XI) the study provides both point measures and measures of variability for at least one key outcome (35). And it categorizes the quality of studies based on the scores assessed: studies with a score below 6 are considered low quality, studies with a score of 6–7 are considered good quality, and studies with a score greater than 7 are considered excellent quality (36,37).

GRADEprofiler software was used to assess the level of evidence quality for outcome measures. The quality included five downgrading factors: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, other considerations. The quality of evidence was divided into four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low.

Two reviewers (Y.Z. and M.Z.) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. If the results of the two authors differed, a third person (K.X.) participated in the discussion and decided on the final consensus.

Risk of bias

Two reviewers (Y.Z. and M.Z.) completed the risk-of-bias assessment independently. Dispute between the reviewers was resolved through discussion, or referred to the third person (K.X.) when necessary. We used the version 2 of the Cochrane tool to access the risk of bias (RoB2) (38,39). Each study was assessed for five areas: randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. And the classifications of bias risk included low risk of bias, uncertain, and high risk of bias. If at least one of these five domains is rated as high risk, the overall score will be rated as high risk. If none of the domains are rated as high risk, but at least one domain is rated as some concern, the overall score will be rated as some concern. If all five domains are low risk, the overall score is low risk. Results were indicated by green, yellow and red color circles respectively.

Statistical analysis

The Review Manager 5.4 software was used for meta-analyses. As the outcome measures were continuous variables, the standardized mean differences (SMDs) of score changes were calculated as pool effect sizes, and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the statistical results was reported. The Chi-squared test and I2 statistic were used to determine the heterogeneity of studies. And Z tests were used to compare differences in the subgroup’s overall effect sizes. A P value less than 0.05 indicates that the difference is statistically significant. The fixed-effect model was used when the heterogeneity test showed no statistically significant difference (I2<30%, P>0.05). When the heterogeneity test showed a statistically significant difference (I2>30%, P<0.05), a random-effects model was used (40). Subgroup analyses or sensitivity analyses is required if heterogeneity is large.

Results

Study selection

Initially, 708 studies were retrieved from five databases after searching. After removing duplicate studies, 492 studies were screened for titles and abstracts and 451 of them were removed for not being relevant, not having full texts or not meeting the eligibility criteria. As a result, 15 studies (41-55) were included in this review and 10 (44-47,50-55) of that were included in meta-analysis, and five of these RCTs were not included in the meta-analysis because data could not be extracted or outcome measures could not be combined. The PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1) described the screening and selection process of studies.

The studies included in this systematic review and meta-analysis were published between 2007 (49) and 2023 (42), covering several nations including America (48-50,54), Canada (41,43,55), Italy (53), China (44,52), Thailand (51), Korea (47), and India (42,45,46).

Participant characteristics

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of participants included in this study. A total of 366 participants with CP (261 hemiplegic, 55 diplegic, 30 quadriplegic) were included in those fifteen studies. Thirteen studies (41-44,46-52,54,55) included 162 females and 176 males. Gender was not reported for 28 participants in two studies (45,53). The mean age of participants ranged from 2.5 to 22 years. One study (48) included four participants with CP older than 18 years but only in the sham stimulation group, and this study was not included in the meta-analysis, only included in the systematic review for descriptive analyses. And the level of MACS ranged from levels I to IV.

Table 3

| Intervention type | Study | Nation | Sample size (M/F) | Treatment group, n | Control group, n | Age (years), range or mean ± SD | Type of CP | MACS level | Adverse event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rTMS | Kirton, 2016 | Canada | 23 (16/7) | 12 | 11 | 11.96±3.9 | Hemiparetic CP | – | 11% mild and self-limiting headache; tingling, nausea <3% |

| Wu, 2022 | China | 35 (14/21) | 17 | 18 | 3.93±1.0 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=19) | Headache (n=1), relieved after several minutes |

|

| Level II (n=16) | |||||||||

| Valle, 2007 | America | 17 (8/9) | 11 | 6 | 9.2±3.4 | Spastic quadriplegia CP | – | No serious adverse events | |

| Gillick, 2014 | America | 19 (9/10) | 10 | 9 | 8–17 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=4) | Self-limiting headache; cast irritation | |

| Level II (n=14) | |||||||||

| Level III (n=1) | |||||||||

| Gupta, 2019 | India | 20 (–/–) | 10 | 10 | 2–15 | Spastic CP | – | No report adverse events | |

| Gupta, 2016 | India | 20 (16/4) | 10 | 10 | 7.99±4.66/8.41±4.32 | Hemiparetic CP (n=2) | – | No report adverse events | |

| Spastic diplegic CP (n=11) | |||||||||

| Quadriplegic CP (n=7) | |||||||||

| Gupta, 2023 | India | 46 (30/16) | 23 | 23 | 5–15 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=1) | No serious adverse events were seen | |

| Level II (n=23) | |||||||||

| Level III (n=22) | |||||||||

| tDCS | Inguaggiato, 2019 | Italy | 8 (–/–) | 3 | 5 | 17.5±6.1 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=2) | Transient and slight discomfort (headache, neck pain, scalp pain, burning, tingling, drowsiness, and so on) |

| Level II (n=3) | |||||||||

| Level III (n=3) | |||||||||

| Carlson, 2018 | Canada | 15 (11/4) | 7 | 8 | 12.1±3.0 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I–IV | No report adverse events | |

| Salazar Fajardo, 2022 | Korea | 24 (12/12) | 14 | 10 | 5.25±2.1 | Spastic unilateral (n=9) | – | No report adverse events | |

| Spastic bilateral CP (n=15) | |||||||||

| Nemanich, 2019 | America | 20 (9/11) | 10 | 10 | 12.75±4.17 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=2) | Headache and itchiness | |

| Level II (n=16) | |||||||||

| Level III (n=1) | |||||||||

| Level IV (n=1) | |||||||||

| Aree-uea, 2014 | Thailand | 46 (24/22) | 23 | 23 | 13.5±3.1 | Spastic diplegia (n=29) | – | Erythematous rash (n=1) | |

| Spastic hemiplegia (n=11) | |||||||||

| Spastic quadriplegia CP (n=6) | |||||||||

| He, 2022 | China | 30 (15/15) | 15 | 15 | 3.96±0.94 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=26) | The proportion of dizziness (n=1), burning sensation (n=1), tingling (n=2), and itching (n=1) | |

| Level II (n=4) | |||||||||

| Gillick, 2018 | America | 20 (9/11) | 10 | 10 | 12.75±4.17 | Hemiparetic CP | – | Headache and itchiness | |

| Kirton, 2017 | Canada | 23 (15/8) | 12 | 11 | 11.8±2.7 | Hemiparetic CP | Level I (n=7) | Itching (39%), headache (n=3), mild burning (n=3), or unpleasant tingling (n=1) | |

| Level II (n=16) |

CP, cerebral palsy; F, female; M, male; MACS, manual ability classification system; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; SD, standard deviation; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

Characteristics of stimulation

Seven studies analyzed the effect of rTMS (41,42,44-46,49,50), while eight studies analyzed tDCS (43,47,48,51-55). As shown in Table 4, characteristics of NIBS included the content of intervention program, site of stimulation, stimulus parameters (intensity and frequency), total duration, duration of each session, number of sessions, outcome measures, and assessment time points.

Table 4

| Intervention type | Study | Content of intervention program | Site of stimulation | Stimulus parameter | Duration | Minutes (pulse)/session | Number of NIBS sessions | Outcomes measured | Assessment time points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tDCS | Inguaggiato, 2019 | TG: active tDCS | The M1 of the affected or more affected hemisphere | Anodal tDCS, 1.5 mA | – | 20 minutes | 2 | BBT | T0: baseline |

| CG: sham tDCS | HGS | T1: immediately | |||||||

| T2: 90 minutes | |||||||||

| Carlson, 2018 | TG: goal-directed motor learning therapy camp + real tDCS | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Cathodal tDCS, 1.0 mA, 0.04 mA/cm2 |

2 weeks | 20 minutes | 10 | COPM | T0: baseline | |

| AHA | T1: 1 week post-intervention | ||||||||

| CG: goal-directed motor learning therapy camp + sham tDCS | MA | T2: 8 weeks post-intervention | |||||||

| BBT | |||||||||

| Salazar Fajardo, 2022 | TG: tDCS + NDT | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Anodal tDCS, 1 mA | 5 weeks | 20 minutes | 15 | BBT | T0: baseline | |

| CG: the only NDT | MAS | T1: post-intervention | |||||||

| T2: 1 month follow-up | |||||||||

| Nemanich, 2019 | TG: active tDCS + CIMT | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Cathodal tDCS, 0.7 mA | 10 days | 20 minutes | 10 | AHA | T0: 11 days prior to intervention | |

| CG: sham tDCS + CIMT | T1: 5 days after intervention | ||||||||

| T2: 6 months after intervention | |||||||||

| Aree-uea, 2014 | TG: PT + active tDCS | The M1 of the affected or more affected hemisphere | Anodal tDCS, 1 mA | 5 days | 20 minutes | 5 | MAS | T0: before treatment | |

| CG: PT + sham tDCS | ROM | T1: immediately after treatment | |||||||

| T2: 24- and 48-hour follow-up | |||||||||

| He, 2022 | TG: active tDCS | The M1 of the affected or more affected hemisphere | Anodal tDCS, 1.5 mA | 2 days | 20 minutes | 2 | GMFCS | T0: baseline | |

| CG: sham tDCS | BBT | T1: immediately | |||||||

| MA 2 | T2: 90 minutes | ||||||||

| MAS | T3: 24 hours | ||||||||

| Gillick, 2018 | TG: CIMT + active tDCS | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Cathodal tDCS, 0.7 mA | 10 days | 20 minutes | 10 | AHA | T0: 2 weeks prior to intervention | |

| CG: CIMT + sham tDCS | COPM | T1: 1 week after intervention | |||||||

| Grip strength | T2: 6 months | ||||||||

| Kirton, 2017 | TG: active tDCS + motor learning therapy | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Cathodal tDCS, 1 mA, 0.04 mA/cm2 | 2 weeks | 20 minutes | 10 | COPM | T0: baseline | |

| AHA | T1: 1 week | ||||||||

| CG: sham tDCS + motor learning therapy | – | – | – | – | – | MA | T2: 2 months | ||

| BBT | |||||||||

| ABILHAND-Kids | |||||||||

| HGS | |||||||||

| rTMS | Kirton, 2016 | TG: rTMS (+) + CIMT (+) | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Intensity 90% resting motor threshold frequency 1 Hz (1,200 stimuli) | 2 weeks | 20 minutes | 10 | AHA | T0: baseline |

| CG: rTMS (−) + CIMT (+) | COPM | T1: 1 week postintervention | |||||||

| MA | T2: 2 months postintervention | ||||||||

| PedsQL | T3: 6 months postintervention | ||||||||

| BBT | |||||||||

| Grip strength | |||||||||

| ABILHAND-Kids | |||||||||

| Wu, 2022 | TG: CIMT + active TMS | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Intensity 90% resting motor threshold frequency 1 Hz | 10 days | 20 minutes | 10 | MACS | T0: baseline | |

| CG: CIMT + sham TMS | COPM | T1: 2 weeks post-intervention | |||||||

| MA 2 | T2: 6 months post-intervention | ||||||||

| MAS | |||||||||

| SCUES | |||||||||

| Valle, 2007 | TG: 1 Hz/5 Hz active rTMS | The motor cortex | Intensity 90% resting motor threshold frequency 5 Hz/1 Hz | 5 days | 1,500 pulses | 5 | MAS | T0: baseline | |

| CG: sham rTMS | ROM | T1: the end of the treatment | |||||||

| Gillick, 2014 | TG: CIMT + active rTMS | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Intensity 90% resting motor threshold frequency 1 Hz (6 Hz priming) | 2 weeks | 20 minutes | 5 | AHA | T0: baseline | |

| CG: CIMT + sham rTMS | COPM | T1: 2 days after the intervention | |||||||

| Gupta, 2019 | TG: PT + rTMS | The motor cortex | Frequency 5 Hz | 20 days | 15 minutes | 20 | MAS | T0: baseline | |

| CG: only PT | T1: post-intervention | ||||||||

| Gupta, 2016 | TG: standard therapy + rTMS | The motor cortex | Frequency 5 Hz/10 Hz (1,500 pulses) | 4 weeks | 15 minutes | 20 | MAS | T0: baseline | |

| CG: only standard therapy | T1: post-intervention | ||||||||

| Gupta, 2023 | TG: mCIMT + real rTMS | The contralesional primary motor cortex (M1) | Intensity 90% resting motor threshold frequency 1 Hz (6 Hz priming) | 4 weeks | 20 minutes | 10 | QUEST | T0: baseline | |

| CG: mCIMT + sham rTMS | CP-QOL | T1: post-intervention | |||||||

| Speed and strength measures | T2: 12 weeks post-intervention |

AHA, Assisting Hand Assessment; BBT, Box and Block Test; CG, control group; CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; COPM, Canadian Occupational Performance Measure; CP-QOL, Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life; GMFCS, gross motor function classification system; HGS, Hand Grip Strength; MACS, manual ability classification system; MA, Melbourne Assessment; MAS, Modified Ashworth Scale; mCIMT, modified CIMT; NDT, neurodevelopmental treatment; PedsQL, pediatric quality of life inventory; PT, physiotherapy; QUEST, Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; ROM, range of motion; SCUES, the selective control of the upper extremity scale; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation; TG, treatment group; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation.

For the site of stimulation, 10 studies (41-44,47,48,50,51,54,55) targeted the contralesional hemisphere primary motor cortex, two (52,53) focused on the affected or more affected hemisphere primary motor cortex, and three studies (45,46,49) did not specify beyond the motor cortex. Intensity of rTMS is 90% resting motor threshold with frequency of 1 or 5 Hz. And intensity of tDCS are 0.7 mA (48,54), 1 mA (43,47,51,55), and 1.5 mA (52,53). Four studies (47,51-53) used anodal tDCS for the affected or more affected hemisphere and four (43,48,54,55) used cathodic tDCS for the contralesional hemisphere. One study (49) used 1500 pulses as the session length, two studies (45,46) conducted each session for 15 minutes, and the remaining studies lasted 20 minutes per session.

A variety of outcome measures were used in the included studies. Six studies (41,43,48,50,54,55) used AHA to evaluate the function of the affected hand during collaborative movement of hands (56,57), six (41,43,44,50,54,55) used COPM to evaluate performance and satisfaction in occupational activities, five (41,43,44,52,55) used MA [two studies (44,52) used MA 2] to evaluate function and quality of upper extremity, six (41,43,47,52,53,55) used BBT to evaluate hands flexibility, seven (44-47,49,51,52) used MAS to assess the muscle tone of upper extremity, two (49,51) used range of motion (ROM) to evaluate the joint function of upper extremity, two (41,55) used ABILHAND-Kids to evaluate hands-on ability, three (41,53,55) used grip strength to evaluate muscle strength, and one (42) used Quality of Upper Extremity Skills Test (QUEST) to evaluate the quality of upper extremity function and movement patterns in children with CP.

The intervals from treatment to follow-up evaluation included immediately (45-47,49,51-53), 90 minutes (52,53), 24 hours (51,52), 48 hours (51), 1 week (41,43,54,55), 2 weeks (44), 1 month (47), 2 months (41,43,55), 12 weeks (42), and 6 months (41,44,48,54).

Assessment of quality

The PEDro scale was used in this systematic review and meta-analysis for assessment of quality. The PEDro scores of the included studies is listed in Table 5. Six studies (41,42,48,51,54,55) had excellent quality, six studies (45,46,49,50,52,53) had good quality, and three studies (43,44,47) had low quality.

Table 5

| Study | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rTMS | ||||||||||||

| Kirton et al. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Wu et al. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 5 |

| Valle et al. | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Gillick et al. | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Gupta et al., 2019 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| Gupta et al., 2016 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 6 |

| Gupta et al., 2023 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| tDCS | ||||||||||||

| Inguaggiato et al. | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 6 |

| Carlson et al. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | 6 |

| Salazar Fajardo et al. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 5 |

| Nemanich et al. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| Aree-uea et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 10 |

| He et al. | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Gillick et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| Kirton et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

The PEDro scale includes 11 items, but only Q2–Q11 (10 items) contribute to the total score (range, 0–10). Q1 serves solely as a screening criterion for study validity and does not contribute to the total score. PEDro, Physiotherapy Evidence Database; Q, question; rTMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; tDCS, transcranial direct current stimulation.

The quality of the evidence for the outcome measures of the included studies was assessed using the GRADEprofiler software. A total of eight outcome measures (three for rTMS and five for tDCS) were included. Among them, there was one low-quality measure and two very low-quality outcome measures of rTMS. There were four low-quality outcome measures and one very low-quality outcome measures for tDCS, as shown in Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment

The version 2 of the Cochrane tool was used to access the risk of bias. The results are shown in Figure 3. Five studies (44-48) were at high risk of bias during randomization, five (41,43,49,52,53) at some concern, and five (42,50,51,54,55) at low risk. One study (47) was at high risk of the bias from the established intervention, seven (43-46,49,52,53) at some concern, and the rest (41,42,48,50,51,54,55) at low risk. Bias for missing outcome data were at low risk in all fifteen studies. Two (45,46) were at some concern of bias for outcome measures and the rest at low risk. Two (41,48) were at high risk of bias for selective reporting of results, eight (43-47,49,51,53) at some concern, and the remaining five (42,50,52,54,55) at low risk. The overall risk of bias was five (41,45-48) at high risk, six (43,44,49,51-53) at some concern, and four (42,50,54,55) at low risk.

Effectiveness of NIBS: meta-analysis

NIBS including rTMS and tDCS were used in 10 studies (44-47,50-55) for meta-analysis. These studies using rTMS as a stimulation intervention assessed upper extremity function in 76 participants, and tDCS as a stimulation intervention evaluated upper extremity function and spasticity in 181 participants.

COPM

In two studies of tDCS, COPM was used to assess the post and follow-up effects in the occupational activities including two components: performance and satisfaction. Heterogeneity existed (SMD =0.73; 95% CI: 0.14 to 1.32; P=0.01; I2=70%), and we divided the groups into two subgroups: performance and satisfaction. For the performance subgroup, we selected a random-effects model (SMD =0.71; 95% CI: −0.17 to 1.60; P=0.12; I2=73%). For the satisfaction subgroup, we chose a random-effects model (SMD =0.76; 95% CI: −0.15 to 1.66; P=0.10; I2=74%). The results of the analysis were not statistically significant for both subgroups, as shown in Figure 4.

COPM was also used to assess occupational performance related to daily activities in three studies of rTMS. There were no significant changes in performance (SMD =−0.22; 95% CI: −0.73 to 0.30; P=0.41; I2=0%) or satisfaction (SMD =−0.11; 95% CI: −0.62 to 0.40; P=0.67; I2=0%) scores using a fixed-effects model, as shown in Figure 4.

BBT

BBT was used to assess the effects of different time point in two studies of tDCS in the coordination of affected hand or unaffected hand, as shown in Figure 5.

The BBT scores of the affected hand changed significantly in overall effect using a fixed-effect model (SMD =0.50; 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.81; P=0.002; I2=0%). The BBT scores of the affected hand changed significantly in post (SMD =0.68; 95% CI: 0.02 to 1.34; P=0.044; I2=0%) and 90-minute effect (SMD =0.69; 95% CI: 0.02 to 1.36; P=0.04; I2=0%); There was no significant changes at short-term (SMD =0.44; 95% CI: −0.15 to 1.02; P=0.14; I2=0%) and long-term follow-up effect (SMD =0.29; 95% CI: −0.29 to 0.87; P=0.33; I2=0%).

However, there was no significant change in the BBT score of the unaffected hand at post (SMD =0.07; 95% CI: −0.57 to 0.71; P=0.83; I2=0%), 90-minute (SMD =0.04; 95% CI: −0.60 to 0.68; P=0.90; I2=0%), short-term (SMD =0.25; 95% CI: −0.33 to 0.83; P=0.40; I2=0%), and long-term follow-up effect (SMD =0.31; 95% CI: −0.27 to 0.89; P=0.30; I2=0%) using a fixed-effect model.

MAS

MAS was used to assess improvement of muscle tone in two studies of tDCS, as shown in Figure 6. There was a significant change in MAS scores (SMD =−0.51; 95% CI: −0.99 to −0.03; P=0.04; I2=0%).

MAS was used to assess muscle tone of biceps and wrist extensor in two studies of rTMS, as shown in Figure 6. There were no significant changes in MAS scores in biceps (SMD =0.16; 95% CI: −0.46 to 0.78; P=0.61; I2=0%) or wrist extensor (SMD =−0.13; 95% CI: −0.75 to 0.49; P=0.67; I2=0%).

AHA

AHA was used to assess the post and follow-up effects in two studies of tDCS in the improvement of upper extremity function on the affected side during collaborative movement of hands, as shown in Figure 7. There was no significant change in AHA scores, either post (SMD =0.23; 95% CI: −0.37 to 0.83; P=0.46; I2=0%) or follow-up effect (SMD =0.12; 95% CI: −0.48 to 0.72; P=0.69; I2=0%) using a fixed-effect model.

HGS

HGS was used to assess improvement of muscle strength in two studies of tDCS, as shown in Figure 7. There was no significant change in HGS scores at overall (SMD =−0.06; 95% CI: −0.60 to 0.48; P=0.83; I2=0%) and post effect (SMD =0.03; 95% CI: −0.73 to 0.79; P=0.94; I2=0%) using a fixed-effect model.

Safety and adverse events

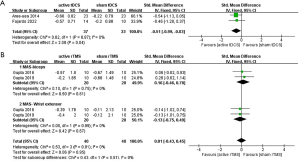

We evaluated the safety and tolerability of NIBS by analyzing adverse events and dropouts, as shown in Figure 8. We performed a meta-analysis of all fifteen studies, and there is no difference in dropouts between active and sham stimulation groups, with only three dropouts in each group. The reasons for dropouts were botulinum toxin injection, disease progression, and distance.

All studies discussed adverse events that occurred during the trials, with the exception of three studies (43,45,47) that no information on adverse events was provided. None of the fifteen studies observed serious adverse effects, instead, all reported adverse event were mild and transient discomfort. Headache was the most common adverse event, with about 8% patients experienced headaches in three studies (41,44,55) in total. There were also patients with headache in Gillick et al.’s 2014 (50) and 2018 (54) studies, as well as in the studies of Inguaggiato et al. (53), Nemanich et al. (48), and Gupta et al. (42), but the incidence was not reported. Tingling was the second most common symptom, reported in multiple studies. About 5% patients experienced tingling in three studies (41,52,55); In Inguaggiato et al.’s study (53), patients also experienced tingling. There were also cases with itching (48,52,54,55), burning sensation (52,53,55), dizziness (42,52), nausea (41), etc. reported. In Aree-uea et al.’s study (51), one participant developed an erythematous rash and mild skin burn, but there was no pain, peeling, or infection. The rash resolved spontaneously within 2 hours, and the skin burn resolved within 3 days without scar. Notably, in Gupta et al.’s study (42), one child who had a history of epilepsy developed vacant stare lasting for a few seconds, within a few hours after the intervention, though this occurred in the sham rTMS group.

Discussion

NIBS regulates brain activity and neuroplasticity by regulating cerebral cortical excitability (58,59), thereby affecting the function innervated by the corresponding brain region. The novelty of our study lies in searching and summarizing the effectiveness and safety of NIBS for improving upper extremity function in children with CP, along with conducting a quantitative meta-analysis which had not been done in previous related studies. Our findings suggest for the first time that tDCS is effective in improving spasticity (MAS), and hand fine motor function, especially hand dexterity in children with CP. Meanwhile, our results have certain clinical and practical significance for relevant healthcare professionals. First, the results provide evidence for the safety of NIBS in children with CP, which is very important for professionals to apply NIBS in clinical practice; second, the effectiveness of tDCS provides professionals with an evidence-based auxiliary treatment method, and medical professionals should regard it as part of a comprehensive rehabilitation plan rather than a single treatment; finally, the results cautiously show that different stimulation parameters could be targeted to treat different dysfunction.

Improvement of upper extremity function

Seven studies analyzed the effect of rTMS in this systematic review (41,42,44-46,49,50). These articles used assessment tools such as AHA, COPM, MA, BBT, MAS, etc. Two of the studies used COPM and two used MAS for outcome assessment in meta-analysis, but neither showed statistically significant score changes. This is consistent with the results of Metelski et al.’s systematic review (27), which reported little or no significant impact for upper extremity dysfunction outcomes after using rTMS. On the one hand, the number of studies retrieved for the particular research question—improving upper extremity function in CP children through rTMS—was relatively small. Consequently, the number of studies that could be incorporated into the systematic review and meta-analysis was limited. On the other hand, COPM mainly evaluates the ability of occupational activities, which place relatively higher requirements for upper extremity and hand function (60,61), and scores may be influenced by the parents and patients’ own subjective judgment. Remarkably, changes in upper extremity may be different in body structure and function outcomes after rTMS. As mentioned in Metelski et al.’s review (27), there was improvement in the ROM of the thumb, wrist, and elbow of children with CP after using rTMS in some RCTs, but these changes in body structure and function did not necessarily translate into improvements in upper extremity function without supplementary interventions.

Eight studies analyzed the effect of tDCS (43,47,48,51-55). Six studies using AHA, COPM, BBT, HGS, MAS as assessment instruments were included in meta-analysis. Among them, score changes of BBT on affected hand, MAS were statistically significant. The results of meta-analysis of MAS suggested that tDCS had some effectiveness in improving spasticity. This is inconsistent with the results of Metelski et al.’s systematic review (27), which found little or no statistically significant improvement in the outcome of upper extremity dysfunction after using tDCS. This discrepancy may stem from differences in the articles included in the analyses between the two studies, as well as differences in supplementary interventions, study design, and tDCS parameters. One study (62) suggested that tDCS combined with sensorimotor training significantly activated the motor cortex. Most of the non-significant results in our meta-analysis may be due to the fact that the effectiveness of NIBS is not generalized to the improvement of functional tasks, and the effectiveness of NIBS in combination with other interventions need to be further explored.

In our study, tDCS did not significantly improve hand muscle strength and occupational activity in children with CP, but it was different in adults. Significant improvement in score on outcome measures of related upper extremity occupational activity after tDCS was reported in a meta-analysis (63) of adult stroke. And another study (64) in adults with stroke reported significant improvement in hand muscle strength after tDCS. This disparity may be due to the differential impact of tDCS on the developing brain of children compared to the mature brain of adults (65).

In addition, rTMS and tDCS exhibit different effects, which may be due to differences in their mechanisms of action. And different stimulation parameters may affect the effectiveness of tDCS and rTMS. We hypothesize that the optimal parameters for each modality may vary depending on clinical experience, different functional impairments, and that future studies should explore these parameters in more detail to improve the effectiveness of NIBS interventions.

Stimulation parameters

Seven studies used rTMS (41,42,44-46,49,50). The study by Valle et al. showed that there was no statistically significant improvement in spasticity after low-frequency or sham rTMS, while there was a statistically significant improvement in spasticity after high-frequency rTMS (49). It indicated that the high frequency (5 Hz) is better than the low frequency (1 Hz) in improving spasticity in some degree. The advantage of low-frequency rTMS is that it directly stimulates the unaffected cortex and indirectly acts on the affected cortex, which is a good choice when there is some organic damage to the affected cortex and the risk of direct stimulation is high (66,67). And one study (68) showed that although both high- and low-frequency rTMS had a positive effect on motor recovery and promote the reorganization of the motor network in stroke patients, high-frequency rTMS may be more conductive to the functional connectivity reorganization of the motor network and have greater benefit to the motor recovery.

Eight studies used tDCS, most of which use the stimulation intensity of 1 mA (43,47,48,51-55). For anodal tDCS, the stimulation was consistently applied over the primary motor cortex (M1) of the affected or more affected hemisphere. Conversely, cathodal tDCS targeted the contralesional primary motor cortex (M1). One study (69) reported that cathodal tDCS is superior to anodal or bilateral stimulation in improving ADL after stroke. The relative advantage of cathodal tDCS may be due to insufficient inter-hemisphere inhibition, leading to downregulation of the overactive unaffected brain hemispheres, thereby restoring the balance of excitatory and inhibitory interactions between both hemispheres (70-72). However, due to the insufficient number of studies included in this review, it was not possible to compare the effects of anodal stimulation with cathodal stimulation.

According to our meta-analysis, several parameters could be summarized to target different dysfunction. In children with CP, 1 mA anodal tDCS of at least five sessions of 20 minutes per session may be effective in improving spasticity; 1.5 mA anodal tDCS of two sessions of 20 minutes per session may be effective in improving the fine motor function, especially flexibility of hands. Thus, different stimulation parameters need to be used for children with CP in different conditions, and knowing these parameters could enhance the clinical application of NIBS as an adjunctive therapy of CP in children.

Safety and tolerability

As shown in the results, there were only three dropouts in each group. The low number of dropouts and loss to follow-up may be due to small sample sizes and strict adherence to inclusion and exclusion criteria. And there were no serious adverse events reported in either rTMS or tDCS. The most serious adverse events mentioned in this study were erythematous rash and mild skin burns, all of which healed quickly. The other adverse events such as headache, tingling, itching, burning sensation, dizziness, and nausea were transient and mild.

Among all the included RCTs, some studies excluded unstable (41,43,55) or uncontrolled epilepsy (44,49,52), some (48,50,54) excluded people who had history of epilepsy in the past 2 years, and some (47,51,53) considered only patients with no history of epilepsy. After the end of the trials, none of the patients experienced adverse effects of epilepsy. Therefore, there is not enough evidence to suggest that NIBS induces epilepsy in patients without a history of epilepsy or in stable epilepsy when safety guidelines (30,73) are followed. Overall, our results demonstrated that NIBS is tolerable for children when adhere to safety guidelines (30,73).

Limitations

The RCTs in this meta-analysis had small sample sizes, which may limit the strength of our conclusions and the applicability of our findings to a wider population or setting, so the interpretation of the results needs to be more rigorous. We emphasize the need for further research on a larger and more diverse sample. Also, due to the limited number of articles included, we were unable to quantitatively analyze and compare the effects of NIBS in combination with other interventions. In addition, this systematic review analyzed only a subset of outcomes, and analyses of improvements in upper extremity function was not comprehensive enough. Potential bias exists as only English-language articles were included in this systematic review and full texts were not available for some article when searching databases and selecting studies. Finally, only RCTs were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis, with case reports and non-RCTs being excluded.

Conclusions

This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that rTMS and tDCS are safe and tolerable for children with CP. Current evidence suggests that when safety guidelines are followed, NIBS does not induce seizures in pediatric patients with no history of epilepsy or stable epilepsy. And tDCS is effective in improving upper extremity dysfunction such as fine motor function especially hand dexterity, and in reducing upper extremity spasticity in children with CP. However, the effectiveness of rTMS remains uncertain due to the limited number of RCTs included in this meta-analysis. In conclusion, NIBS seems safe for use in children with CP and could be used as an adjunct to the clinic rehabilitation in children with CP. Nevertheless, given the paucity of studies on NIBS for upper extremity dysfunction in children with CP, further high-quality RCTs are needed to establish robust evidence and treatment parameters.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-488/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-488/prf

Funding: The work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-24-488/coif). All authors report funding from the Featured Clinical Technique of Guangzhou (No. 2023C-TS59), the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Project (No. 2024A03J01274), and the Plan on Enhancing Scientific Research in Guangzhou Medical University (No. GMUCR2024-02020). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Christine C, Dolk H, Platt MJ, et al. Recommendations from the SCPE collaborative group for defining and classifying cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007;109:35-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenbloom L. Definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Definition, classification, and the clinician. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl 2007;109:43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadowska M, Sarecka-Hujar B, Kopyta I. Cerebral Palsy: Current Opinions on Definition, Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification and Treatment Options. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2020;16:1505-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Surveillance of cerebral palsy in Europe: a collaboration of cerebral palsy surveys and registers. Surveillance of Cerebral Palsy in Europe (SCPE). Dev Med Child Neurol 2000;42:816-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Şahin S, Köse B, Aran OT, et al. The Effects of Virtual Reality on Motor Functions and Daily Life Activities in Unilateral Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. Games Health J 2020;9:45-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li N, Zhou P, Tang H, et al. In-depth analysis reveals complex molecular aetiology in a cohort of idiopathic cerebral palsy. Brain 2022;145:119-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Avila-Soto F, Kakooza AM, Ueda K, et al. Studies of CP Prevalence: Disparities in Authorship, Citations, and Geographic Location. Pediatr Neurol 2023;143:59-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Makki D, Duodu J, Nixon M. Prevalence and pattern of upper limb involvement in cerebral palsy. J Child Orthop 2014;8:215-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ouyang RG, Yang CN, Qu YL, et al. Effectiveness of hand-arm bimanual intensive training on upper extremity function in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2020;25:17-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cieza A, Causey K, Kamenov K, et al. Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021;396:2006-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoare BJ, Wallen MA, Thorley MN, et al. Constraint-induced movement therapy in children with unilateral cerebral palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;4:CD004149. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang FA, Lee TH, Huang SW, et al. Upper limb manual training for children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil 2023;37:516-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shum LC, Valdes BA, Hodges NJ, et al. Error Augmentation in Immersive Virtual Reality for Bimanual Upper-Limb Rehabilitation in Individuals With and Without Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng 2020;28:541-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gygax MJ, Schneider P, Newman CJ. Mirror therapy in children with hemiplegia: a pilot study. Dev Med Child Neurol 2011;53:473-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Narimani A, Kalantari M, Dalvand H, et al. Effect of Mirror Therapy on Dexterity and Hand Grasp in Children Aged 9-14 Years with Hemiplegic Cerebral Palsy. Iran J Child Neurol 2019;13:135-42.

- Elbanna ST, Elshennawy S, Ayad MN. Noninvasive Brain Stimulation for Rehabilitation of Pediatric Motor Disorders Following Brain Injury: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:1945-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YW, Shin IS, Moon HI, et al. Effects of non-invasive brain stimulation on freezing of gait in parkinsonism: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2019;64:82-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang A, Thickbroom G, Rodger J. Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of the Brain: Mechanisms from Animal and Experimental Models. Neuroscientist 2017;23:82-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braun R, Klein R, Walter HL, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation accelerates recovery of function, induces neurogenesis and recruits oligodendrocyte precursors in a rat model of stroke. Exp Neurol 2016;279:127-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng L, Tian L, Wang T, et al. Effects of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) for executive function on subjects with ADHD: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2023;13:e069004. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hara T, Shanmugalingam A, McIntyre A, et al. The Effect of Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation (NIBS) on Attention and Memory Function in Stroke Rehabilitation Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:227. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khaleghi A, Zarafshan H, Vand SR, et al. Effects of Non-invasive Neurostimulation on Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci 2020;18:527-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hallett M. Transcranial magnetic stimulation: a primer. Neuron 2007;55:187-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paulus W, Peterchev AV, Ridding M. Transcranial electric and magnetic stimulation: technique and paradigms. Handb Clin Neurol 2013;116:329-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitsche MA, Liebetanz D, Antal A, et al. Modulation of cortical excitability by weak direct current stimulation--technical, safety and functional aspects. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol 2003;56:255-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitsche MA, Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol 2000;527:633-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Metelski N, Gu Y, Quinn L, et al. Safety and efficacy of non-invasive brain stimulation for the upper extremities in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol 2024;66:573-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Antal A, Alekseichuk I, Bikson M, et al. Low intensity transcranial electric stimulation: Safety, ethical, legal regulatory and application guidelines. Clin Neurophysiol 2017;128:1774-809. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bikson M, Grossman P, Thomas C, et al. Safety of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation: Evidence Based Update 2016. Brain Stimul 2016;9:641-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossi S, Hallett M, Rossini PM, et al. Safety, ethical considerations, and application guidelines for the use of transcranial magnetic stimulation in clinical practice and research. Clin Neurophysiol 2009;120:2008-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monte-Silva K, Kuo MF, Hessenthaler S, et al. Induction of late LTP-like plasticity in the human motor cortex by repeated non-invasive brain stimulation. Brain Stimul 2013;6:424-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monte-Silva K, Kuo MF, Liebetanz D, et al. Shaping the optimal repetition interval for cathodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). J Neurophysiol 2010;103:1735-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Morton NA. The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials: a demographic study. Aust J Physiother 2009;55:129-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sherrington C, Herbert RD, Maher CG, et al. PEDro. A database of randomized trials and systematic reviews in physiotherapy. Man Ther 2000;5:223-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, et al. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2003;83:713-21.

- Sun YY, Wang L, Peng JL, et al. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function and language ability in cerebral palsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr 2023;11:835472. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019;10:ED000142. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019;366:l4898. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirton A, Andersen J, Herrero M, et al. Brain stimulation and constraint for perinatal stroke hemiparesis: The PLASTIC CHAMPS Trial. Neurology 2016;86:1659-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta J, Gulati S, Singh UP, et al. Brain Stimulation and Constraint Induced Movement Therapy in Children With Unilateral Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2023;37:266-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carlson HL, Ciechanski P, Harris AD, et al. Changes in spectroscopic biomarkers after transcranial direct current stimulation in children with perinatal stroke. Brain Stimul 2018;11:94-103. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu Q, Peng T, Liu L, et al. The Effect of Constraint-Induced Movement Therapy Combined With Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on Hand Function in Preschool Children With Unilateral Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Preliminary Study. Front Behav Neurosci 2022;16:876567. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gupta M, Rajak BL, Bhatia D, et al. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on motor function and spasticity in spastic cerebral palsy. Int J Biomed Eng Technol 2019;31:365-74.

- Gupta M, Lal Rajak B, Bhatia D, et al. Effect of r-TMS over standard therapy in decreasing muscle tone of spastic cerebral palsy patients. J Med Eng Technol 2016;40:210-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salazar Fajardo JC, Kim R, Gao C, et al. The Effects of tDCS with NDT on the Improvement of Motor Development in Cerebral Palsy. J Mot Behav 2022;54:480-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nemanich ST, Rich TL, Chen CY, et al. Influence of Combined Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation and Motor Training on Corticospinal Excitability in Children With Unilateral Cerebral Palsy. Front Hum Neurosci 2019;13:137. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valle AC, Dionisio K, Pitskel NB, et al. Low and high frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of spasticity. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49:534-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillick BT, Krach LE, Feyma T, et al. Primed low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation and constraint-induced movement therapy in pediatric hemiparesis: a randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol 2014;56:44-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aree-uea B, Auvichayapat N, Janyacharoen T, et al. Reduction of spasticity in cerebral palsy by anodal transcranial direct current stimulation. J Med Assoc Thai 2014;97:954-62.

- He W, Huang Y, He L, et al. Safety and effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on hand function in preschool children with hemiplegic cerebral palsy: A pilot study. Front Behav Neurosci 2022;16:925122. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inguaggiato E, Bolognini N, Fiori S, et al. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS) in Unilateral Cerebral Palsy: A Pilot Study of Motor Effect. Neural Plast 2019;2019:2184398. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gillick B, Rich T, Nemanich S, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation and constraint-induced therapy in cerebral palsy: A randomized, blinded, sham-controlled clinical trial. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2018;22:358-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kirton A, Ciechanski P, Zewdie E, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation for children with perinatal stroke and hemiparesis. Neurology 2017;88:259-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gordon AL. How reliable is the Assisting Hand Assessment for adolescents with unilateral cerebral palsy? Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:886.

- Louwers A, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Boeschoten K, et al. Reliability of the Assisting Hand Assessment in adolescents. Dev Med Child Neurol 2017;59:926-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hameed MQ, Dhamne SC, Gersner R, et al. Transcranial Magnetic and Direct Current Stimulation in Children. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2017;17:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hassanzahraee M, Zoghi M, Jaberzadeh S. How different priming stimulations affect the corticospinal excitability induced by noninvasive brain stimulation techniques: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Neurosci 2018;29:883-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Law M, Baptiste S, McColl M, et al. The Canadian occupational performance measure: an outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther 1990;57:82-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohno K, Tomori K, Sawada T, et al. Measurement Properties of the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure: A Systematic Review. Am J Occup Ther 2021;75:7506205100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Chen Y, Tu S, et al. Dual-tDCS combined with sensorimotor training promotes upper limb function in subacute stroke patients: A randomized, double-blinded, sham-controlled study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2024;30:e14530. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elsner B, Kugler J, Pohl M, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for improving function and activities of daily living in patients after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;CD009645. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Xing G, Shuai S, et al. Low-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for Stroke-Induced Upper Limb Motor Deficit: A Meta-Analysis. Neural Plast 2017;2017:2758097. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vöckel J, Spitznagel N, Markser A, et al. A paucity of evidence in youth: The curious case of transcranial direct current stimulation for depression. Asian J Psychiatr 2024;91:103838. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D'Amico JM, Dongés SC, Taylor JL. High-intensity, low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation enhances excitability of the human corticospinal pathway. J Neurophysiol 2020;123:1969-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maeda F, Keenan JP, Tormos JM, et al. Modulation of corticospinal excitability by repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 2000;111:800-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo Z, Jin Y, Bai X, et al. Distinction of High- and Low-Frequency Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation on the Functional Reorganization of the Motor Network in Stroke Patients. Neural Plast 2021;2021:8873221. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Elsner B, Kwakkel G, Kugler J, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for improving capacity in activities and arm function after stroke: a network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2017;14:95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Pino G, Pellegrino G, Assenza G, et al. Modulation of brain plasticity in stroke: a novel model for neurorehabilitation. Nat Rev Neurol 2014;10:597-608. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nowak DA, Grefkes C, Ameli M, et al. Interhemispheric competition after stroke: brain stimulation to enhance recovery of function of the affected hand. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2009;23:641-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duque J, Hummel F, Celnik P, et al. Transcallosal inhibition in chronic subcortical stroke. Neuroimage 2005;28:940-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woods AJ, Antal A, Bikson M, et al. A technical guide to tDCS, and related non-invasive brain stimulation tools. Clin Neurophysiol 2016;127:1031-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]