Fatigue, anxiety and depression in parents of children with retinoblastoma: a cohort study

Highlight box

Key findings

• Parents of children with retinoblastoma (RB) experienced fluctuations in fatigue, anxiety, and depression. The influencing factors of these psychological distress were the sex of the children, the self-reported health of the parents and family income.

What is known and what is new?

• Parents of children with cancer are also prone to psychological problems such as anxiety, depression and stress, or even major depression.

• This study found that fatigue, anxiety, and depression in parents of children with RB fluctuate and are influenced by multiple factors.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• In clinical practice, healthcare professionals should be aware of the occurrence of fatigue, anxiety, and depression in parents of children with RB, and recommend early assessment and screening for these symptoms in high-risk populations, to achieve early screening, detection, and intervention.

Introduction

Retinoblastoma (RB) is the most common primary ocular malignancy in childhood, with a median age of diagnosis of 23.2 months [interquartile range (IQR) 11.0–36.5 months] (1) and the overall survival rates of the patients at 1, 3, and 5 years were 81%, 83%, and 91%, respectively (2). More than 95% of children develop the disease within 5 years of age (3), and the World Health Organization has advocated RB as a childhood tumor of global concern (4). RB can cause vision loss and become life-threatening if it extends beyond the eye. Family caregivers of cancer patients play a critical role, assisting with daily activities, medications and lifestyle management, and providing informational, emotional and financial support (5). However, caregivers of children with cancer face a heavier care burden (6) and are more prone to fatigue (7). Fatigue can manifest as a physiological response or pathological condition resulting from rest, exercise or stress and is influenced by factors such as mental state and life experiences (8). It can seriously undermine quality of life (9). Parents of children with cancer are also prone to psychological problems such as anxiety and depression (10,11), or even major depression (12). Such conditions can further affect the child’s quality of life, negatively affecting growth and development (13). Although a large body of literature has extensively explored the visual, genetic, and survival implications of RB (2), relatively little research has examined the psychological burden experienced by parents of children with RB. As primary caregivers, these parents are highly susceptible to negative emotions, such as fatigue, anxiety, and depression (10). However, few longitudinal studies have examined the fluctuation of these psychological states and the factors that influence them. This study focuses on the mental health of parents of children with RB and aims to investigate the factors influencing fatigue, anxiety and depression in thereby providing a basis for the development of effective interventions to support these parents.

Objects of study

Convenience sampling was used to select parents of children with RB who attended the ophthalmology ward or outpatient clinic of the Ninth People’s Hospital, affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, starting in March 2020. A follow-up survey was conducted 18 months after completion of the initial survey if participants met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the questionnaire survey. Based on a systematic literature review and expert consultation, this study included a total of 15 independent variables, with a sample size of 5–10 times the number of variables. Considering factors such as incomplete data that may result in a 10% invalid evaluation, the final sample size was calculated to be 83–167 cases. In this study, a total of 85 parents of children with RB were recruited to participate in the survey, and 166 questionnaires were received. The number of valid questionnaires was 162, as 4 parents of children with RB refused to be part of the second survey. Inclusion criteria for pediatric patients: pediatric patients must be diagnosed with RB. Exclusion criteria for pediatric patients: pediatric patients had a history of central nervous system diseases, including but not limited to brain metastases or epilepsy; pediatric patients who had co-existing other malignant tumors, such as neuroblastoma and leukemia. The inclusion criteria for parents included: parents’ age ≥18 years old; no recent history of major amily accidents or acute psychological trauma; and voluntary participation in the survey. The exclusion criteria for parents were previous history of psychosis, depression, or severe cognitive dysfunction. We present this article in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-145/rc).

Methods

Research tools

General Demographic Information Questionnaire

General demographic information about the children with RB included their sex, date of birth, year of diagnosis, diseased eye, disease stage, previous hospitalisation, disease status, and previous treatment; general demographic information about these children’s participating parent included their age, marital status, education level, and health status.

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)

The FSS, developed in 1989 by American scholars Krupp et al. (14), effectively evaluates fatigue levels in patients. It comprises nine items, each rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), with a total score ranging from 0 to 63. Higher scores indicate greater fatigue severity, with scores ≥36 signifying severe fatigue. This scale identifies the severity of fatigue, including in patients with epilepsy (15), the FSS may have limitations in detecting sensitivity over time in healthy or subclinical populations; however, it has been widely used in chronically ill (16) and healthy populations (17), and can provide valuable information to understand the current status of fatigue in this particular population. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for FSS was 0.92.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

The GAD-7 screens for generalised anxiety disorder and assesses symptom severity over the past 2 weeks. It includes seven items rated on a four-point scale (0–3), resulting in a total score between 0 and 21, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity. A GAD-7 total score of ≥10 is typically used as an anxiety screening threshold (18). In our study, we used the GAD-7 to measure overall anxiety levels among parents. The GAD-7 has good reliability, validity, and construct validity (19) and is a rapid, reliable, and valid self-assessment tool to detect the presence of anxiety symptoms in patients.

Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2)

The PHQ-2, extracted from the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), assesses parental depressive symptoms on a scale of 0–3, with 0 meaning “not at all” and 3 meaning “almost every day” (20). It assesses the frequency of depressive mood and loss of speech in the past 2 weeks. A PHQ-2 score >3 has a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 92% for major depression, and the PHQ-2 has been validated and used in China (21).

Data collection methods

The study team informed the purpose, content and methodology to participants through WeChat. Parents who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria completed an online questionnaire through the “WJX.CN” platform. We ensured that the questions were clear and concise, and that complex or ambiguous vocabulary was avoided. Prior to the formal release of the questionnaire, a pre-test was conducted. Parents of a small number of patients with RB were invited to complete the questionnaire, and their feedback was collected. Corrections are then made based on the comments. Only one survey can be submitted per IP address in the questionnaire settings, and informed consent was obtained from all participants. The survey was confidential and anonymous and could only be submitted after it was fully completed. Data were exported at the end of the study for analysis. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. SH9H-2019-T289-2) and informed consent was taken from the parents.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.2.2). Missing data were handled using the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) approach. Quantitative variables conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), and categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. For group comparisons of continuous variables, the independent samples t-test was used when normality was satisfied, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was applied when the normality assumption was violated. Given the repeated measures design, Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) were employed for both univariate and multivariate analyses to account for within-subject correlations. For continuous outcome variables (e.g., fatigue, anxiety, depression scores), GEE models were specified with a Gaussian distribution and an identity link function. Variables with a P value less than 0.05 in univariate analyses were included in the multivariate models. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed P value of <0.05.

Results

Basic information and univariate analysis of children with RB and their parents

The male-to-female ratio was nearly 1:1. The mean age of the children was 4.7±1.4 years, and the correlation coefficients between the age of the children and fatigue, anxiety, and depression were −0.06, 0.00003 and 0.01, respectively. Monocularity was predominantly present in the affected eyes (72.2% of the cases). The disease stages were mostly in the D (37.7%) and E (56.2%) phases, with 74.7% undergoing review. Due to the need for RB treatment, the child had an average of 12.1±8.3 previous hospitalizations, and the correlation coefficients between the number of previous hospitalizations and fatigue, anxiety, and depression were 0.04, 0.11 and 0.11, respectively. The average age of the children’s parents was 32.2±6.9 years, and the correlation coefficients between the average age of the parents and fatigue, anxiety, and depression were 0.01, 0.01 and 0.12, respectively. Most parents were married (97.5%); 62.4% had at least a high school education. Regarding health, 80.24% reported being in good or fair health; 47.5% indicated that the current family income could not meet their children’s medical expenses and 80.2% and 66.7% of the children had previously received intravenous or arterial chemotherapy, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in fatigue scores between parents of different sex of the child and self-reported health (P<0.001). There were statistically significant differences in anxiety scores between parents of different current disease status of the child, self-reported health and family income (P<0.05). There was a statistically significant difference in depression scores between parents of different self-reported health and family income (P<0.01), as shown in Table 1. In this study, no statistically significant difference in baseline characteristics between those who completed the study and those who were lost to follow-up (P>0.05). The baseline characteristics of the children with RB and their parents are detailed in Table S1, along with comparisons of the characteristics of the included and dropout participants.

Table 1

| Subject | Items | Subcategory | N (%) | Fatigue score | Anxiety score | Depression score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | P | Mean ± SD | P | Mean ± SD | P | ||||||

| Child | Sex | Male† | 84 (51.9) | 37.5±12.1 | – | 16.4±6.9 | – | 4.3±2.2 | – | ||

| Female | 78 (48.1) | 43.1±10.1 | <0.001 | 15.6±5.5 | 0.51 | 4.1±1.6 | 0.61 | ||||

| Ocular disease | Left† | 58 (35.8) | 39.0±10.6 | _ | 14.8±5.9 | _ | 4.1±2.0 | _ | |||

| Right | 59 (36.4) | 40.5±11.6 | 0.55 | 16.2±6.2 | 0.31 | 4.1±1.8 | 0.90 | ||||

| Bilateral | 45 (27.8) | 41.4±12.4 | 0.36 | 17.3±6.5 | 0.08 | 4.4±2.0 | 0.59 | ||||

| Tumor stage at diagnosis‡ | A/B/C† | 10 (6.2) | 41.7±9.4 | – | 15.7±5.1 | – | 4.5±2.0 | – | |||

| D | 61 (37.7) | 42.8±9.7 | 0.78 | 17.1±6.5 | 0.48 | 4.5±1.9 | 0.96 | ||||

| E | 91 (56.2) | 38.3±12.5 | 0.38 | 15.3±6.1 | 0.85 | 4.0±1.9 | 0.47 | ||||

| Current disease status | Under treatment† | 41 (25.3) | 39.5±10.9 | – | 18.0±6.6 | – | 4.7±2.1 | – | |||

| Under re-examine | 121 (74.7) | 40.4±11.7 | 0.67 | 15.3±6.0 | 0.02 | 4.0±1.8 | 0.052 | ||||

| Previous treatment modalities: IVC | No† | 32 (19.8) | 40.1±8.99 | – | 14.8±5.9 | – | 4.1±1.8 | – | |||

| Yes | 130 (80.2) | 40.2±12.04 | 0.93 | 16.3±6.3 | 0.23 | 4.2±2.0 | 0.87 | ||||

| Previous treatment modalities: eye removal | No† | 105 (64.8) | 40.1±11.5 | – | 16.3±6.1 | – | 4.3±1.9 | – | |||

| Yes | 57 (35.2) | 40.5±11.6 | 0.86 | 15.6±6.5 | 0.58 | 4.0±2.0 | 0.41 | ||||

| Previous treatment modalities: IAC | No† | 54 (33.3) | 41.8±11.6 | – | 16.5±6.6 | – | 4.2±2.0 | – | |||

| Yes | 108 (66.7) | 39.4±11.4 | 0.27 | 15.8±6.1 | 0.57 | 4.1±1.9 | 0.78 | ||||

| Parents | Marital status | Married† | 158 (97.5) | 40.2±11.6 | – | 16.0±6.2 | – | 4.2±1.9 | – | ||

| (sth. or sb.) else | 4 (2.5) | 42.0±6.5 | 0.45 | 16.2±9.3 | 0.96 | 4.5±2.7 | 0.79 | ||||

| Educational level | Junior high school and below† | 61 (37.6) | 38.2±12.7 | – | 15.5±6.7 | – | 3.7±1.8 | – | |||

| High school or junior college | 38 (23.5) | 39.3±9.8 | 0.69 | 15.8±6.1 | 0.86 | 4.6±2.0 | 0.07 | ||||

| College degree or above | 63 (38.9) | 42.6±10.9 | 0.08 | 16.7±5.9 | 0.37 | 4.4±2.0 | 0.07 | ||||

| Self-reported health | Excellent† | 32 (19.8) | 34.9±13.1 | – | 14.4±5.8 | – | 3.6±1.8 | – | |||

| Good | 68 (42.0) | 39.0±11.2 | 0.08 | 15.3±6.2 | 0.40 | 3.9±1.9 | 0.37 | ||||

| Fair and below | 62 (38.3) | 44.2±9.4 | <0.001 | 17.6±6.3 | 0.01 | 4.8±1.9 | 0.001 | ||||

| Can family income meet children’s medical expenses | Can† | 85 (52.5) | 38.6±11.0 | – | 14.2±5.2 | – | 3.7±1.7 | – | |||

| Can’t | 77 (47.5) | 41.9±11.8 | 0.09 | 18.0± 6.7 | <0.001 | 4.7±2.1 | <0.01 | ||||

†, reference variable; ‡, intraocular retinoblastoma was classified by the International Classification of Retinoblastoma as group A, group B, group C, group D, and group E. Group A: small tumors (≤3 mm), located >3 mm from the fovea and >1.5 mm from the optic disc; group B: tumors >3 mm, macular or juxtapapillary location, or subretinal fluid ≤3 mm from the tumor margin; group C: tumors with focal subretinal or vitreous seeding within 3 mm of the tumor; group D: tumors with diffuse subretinal or vitreous seeding >3 mm from the tumor; group E: extensive retinoblastoma occupying >50% of the globe, possibly with neovascular glaucoma, hemorrhage, or extension to the optic nerve or anterior chamber. IAC, intra-arterial chemotherapy; IVC, intravenous chemotherapy; RB, retinoblastoma; sb., somebody; SD, standard deviation; sth., something.

Factors influencing fatigue, anxiety and depression in parents of children with RB

Factors influencing the total fatigue score of parents of children with RB

Independent factors influencing fatigue in parents of children with RB included the child’s sex and the self-reported health. Details are provided in Table 2.

Table 2

| Items | Estimate | Std.Error | Walf | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant term | 32.88 | 2.10 | 245.01 | <0.001 | 28.76 to 36.99 |

| Sex of child | |||||

| Male† | |||||

| Female | 4.92 | 2.00 | 6.03 | 0.01 | 0.99 to 8.85 |

| Self-reported health | |||||

| Excellent† | |||||

| Good | 3.91 | 2.43 | 2.60 | 0.11 | −0.85 to 8.67 |

| Fair and below | 8.67 | 2.53 | 11.70 | <0.001 | 3.70 to 13.63 |

†, reference variable. CI, confidence interval; RB, retinoblastoma; Std.Error, standard error.

Factors influencing the anxiety of parents of children with RB

Independent factors influencing anxiety include parents’ self-reported health and the family’s income. Results are detailed in Table 3.

Table 3

| Items | Estimate | Std.Error | Walf | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant term | 14.16 | 1.33 | 112.75 | <0.001 | 11.55 to 16.78 |

| Current disease status of the child | |||||

| Under treatment† | |||||

| Under re-examine | −1.83 | 1.07 | 2.92 | 0.09 | −3.93 to 0.27 |

| Self-reported health | |||||

| Excellent† | |||||

| Good | 1.24 | 1.07 | 1.35 | 0.25 | −0.85 to 3.34 |

| Fair and below | 2.90 | 1.11 | 6.86 | 0.01 | 0.73 to 5.07 |

| Can family income meet children’s medical expenses? | |||||

| Can† | |||||

| Can’t | 3.34 | 1.04 | 10.22 | 0.001 | 1.29 to 5.39 |

†, reference variable. CI, confidence interval; RB, retinoblastoma; Std.Error, standard error.

Factors influencing depression in parents of children with RB

Independent factors influencing depression included parents’ self-reported health and the family’s income. Results are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4

| Items | Subcategory | Estimate | Std.Error | Walf | P | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant term | – | 3.122 | 0.345 | 82.05 | <0.001 | 2.45 to 3.80 |

| Self-reported health | Excellent† | |||||

| Good | 0.425 | 0.368 | 1.34 | 0.25 | −0.30 to 1.15 | |

| Fair and below | 1.185 | 0.375 | 9.97 | 0.002 | 0.45 to 1.92 | |

| Can family income meet children’s medical expenses? | Can† | |||||

| Can’t | 0.881 | 0.343 | 6.59 | 0.01 | 0.21 to 1.55 |

†, reference variable. CI, confidence interval; RB, retinoblastoma; Std.Error, standard error.

Fluctuations in fatigue, anxiety and depression in parents of children with RB

Between the independent influences of fatigue, anxiety and depression, the values of the two measurements were fluctuated.

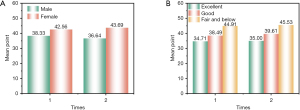

Fluctuations in fatigue scores of RB parents

In the second measurement, fatigue scores decreased for parents of male children but increased for parents of female children. Parents of children in fair and below health consistently reported the highest fatigue scores compared to those in very good and good health (Figure 1).

Fluctuations in anxiety scores of RB parents

In the second measurement, anxiety scores decreased for parents of children with different physical health conditions. However, parents of children whose family income could not meet their children’s medical expenses consistently reported higher anxiety scores than parents who could meet the expenses (Figure 2).

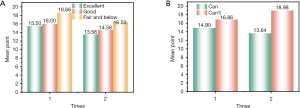

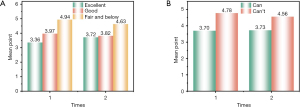

Fluctuations in depression scores of RB parents

Parents of children in fair and below health had the higher depression scores in two surveys compared to parents in very good and good health. Similarly, parents of children whose family income could not meet their children’s medical expenses had higher anxiety scores on both measures than parents of children who could meet their children’s medical expenses (Figure 3).

Discussion

We found that fatigue, anxiety and depression in parents of children with RB fluctuated. The independent factors influencing these emotions were the child’s sex, the parent’s health status and the family’s income.

Parents of female children with RB are more likely to be fatigued than parents of male children

We found that the fatigue level of parents of female children was higher compared to those of parents of male children. This may be because parents are more concerned about the appearance of female children with RB. Although RB treatment principles have shifted from eye removal and external radiation therapy to chemoreduction combined with local therapy (1), chemotherapy remains the primary treatment. However, chemotherapeutic toxicity is prevalent during the treatment of children with tumor, severely affecting their functional status and quality of life (22). Chemotherapy-related dermatoxic reactions, such as alopecia, skin hyperpigmentation, hyperfocalisation, or rash (23), can severely affect the child’s appearance and further aggravate parental fatigue. When faced with these serious side effects, parents may experience a series of psychological problems (24) and even consider giving up treatment. This suggests that healthcare workers may face more difficulties when dealing with chemotherapy toxicity reactions for parents of RB patients. Although eye preservation rate in children with RB has increased significantly in recent years (25), parents are concerned about the prognostic status of their children’s disease, tumor recurrence and eye removal surgery, which may affect the appearance of their female children. Parents may also be more concerned about the impact of the treatment on the growth and development of their female children, leading to potential exacerbation in parental fatigue level. Parental fatigue has been found to have a serious impact on the family (26). Therefore, medical professionals should pay attention to the psychological state of the parents of children with RB, especially the parents of female children, and strengthen the knowledge of the disease and caregiving skills of the parents, thus reducing their caregiving stress and fatigue level.

Parents of children with RB who are in fair and below health themselves have higher levels of fatigue, anxiety and depression

Our results show that parents of children with RB who were in fair health had higher levels of fatigue, anxiety and depression relative to those in excellent health. When a child is diagnosed with cancer, the psychological and physical conditions of the parents are greatly challenged. More parental pain, fatigue and physical symptoms, and more parental distress and pain catastrophising were associated with more paediatric fatigue (27). Fatigue is a state of exertion and exhausted feeling within the individual. Parents of children with cancer may experience not only a severe caregiving burden (6) but also a range of negative psychological problems, including increased distress, anxiety and depression (28,29). Frequent medical visits are often required during the diagnosis and follow-up of the children. Moreover, there is a higher level of fatigue and psychological burden when faced with sudden illness and the financial stress of hospitalisation. Furthermore, families often need to invest more time and energy in planning for life after cancer when adapting to and caring for a child with lifelong needs of RB (30). The physical health of these parents, who are the main decision-makers and primary caregivers of the family, should not be underestimated. Therefore, it is recommended that healthcare professionals provide necessary support and counselling to parents during this period to understand their coping experiences and help them reduce parental stress to improve the physical health of parents, thereby reducing their fatigue, anxiety, and depression levels.

Parents of children with low family income have high levels of anxiety and depression

We found that parents of children with low family income had higher levels of anxiety and depression. The treatment methods for RB are complex and diverse (31), with long cycles, requiring frequent hospitalisations. In our study, 88.9% (144/162) of children had been hospitalised twice or more, and 58.6% (95/162) had over 10 hospitalisations. Each hospital visit imposed a significant financial burden on the parents, especially those with limited or low income. In this study, 47.5% (77/162) of the parents reported that their family income could not meet the medical expenses of their children, and the pressure of raising children was greater. The financial burden due to the treatment increase the risk of parents abandoning the treatment (32), leading to increased anxiety and depression in the parents. Family income affects the quality of life of the family and is also closely related to the psychological well-being of the children’s parents (33). Wang et al.’s study of parents of children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia found that parents with a higher number of child caregivers and higher incomes were found to have lower negative affect (34). Some caregivers have also reported that social support is their main protection against difficulties (24), the ability of parents to utilize their personal resources in the face of significant challenges contributes to the resilience of the parental family system (35). This suggests that healthcare professionals should focus on providing social support and assess the mental health needs of parents with financial challenges to reduce their anxiety and depression. Early and ongoing interventions can help alleviate anxiety and depression and ensure continued care for children with RB.

Limitations

The convenience sampling method used in this study may have limited the generalizability of the research results, and this is acknowledged. Future research should employ more rigorous sampling techniques, such as stratified random sampling, to ensure representative samples. Additionally, the present study is confined to a single center. Future research will expand the sample size and conduct randomized multicenter studies to enhance the robustness of the results. We recognize that using only the PHQ-2 may underestimate the severity or burden of depression. Therefore, we recommend that future studies include the PHQ-9 or other validated follow-up tools to provide a more comprehensive depression assessment. Additionally, online surveys often attract participants who are more tech-savvy, which may result in the sample not fully representing parents of children with RB, particularly those from low-income families. To address this, future research should consider combining paper questionnaires to include participants from different regions and socioeconomic backgrounds, thereby improving the representativeness of the sample and broadening the applicability of the research results.

Conclusions

Fatigue, anxiety and depression in parents of children with RB are fluctuated and influenced by multiple factors. Therefore, in clinical practice, healthcare professionals should be aware of and proactively assess and screen for these symptoms in high-risk populations to achieve early screening, detection and intervention. We suggest that psychological screening should be carried out at key contact points for parents of children with RB during the clinical diagnosis and treatment process. These points include the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up periods. The screening should be carried out by professionally qualified medical personnel (e.g., oncologists and nursing staff), and parents of children with RB who are experiencing psychological difficulties should then be referred to a professional social worker or counsellor. This will improve their mental health through the provision of personalised psychological counselling services. Parents of children with RB will then be referred to professional social workers or counsellors, who will provide personalised psychological counselling services or conduct psycho-educational lectures to improve their mental health.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-145/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-145/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-145/prf

Funding: This study was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-145/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. SH9H-2019-T289-2) and informed consent was taken from the parents.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- The Global Retinoblastoma Outcome Study: a prospective, cluster-based analysis of 4064 patients from 149 countries. Lancet Glob Health 2022;10:e1128-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luo Y, Zhou C, He F, et al. Contemporary Update of Retinoblastoma in China: Three-Decade Changes in Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Treatments, and Outcomes. Am J Ophthalmol 2022;236:193-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wen X, Fan J, Jin M, et al. Intravenous versus super-selected intra-arterial chemotherapy in children with advanced unilateral retinoblastoma: an open-label, mul-ticentre, randomised trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2023;7:613-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schaiquevich P, Francis JH, Cancela MB, et al. Treatment of Retinoblastoma: What Is the Latest and What Is the Future. Front Oncol 2022;12:822330. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- García-Torres F, Jacek Jabłoński M, Gómez Solís Á, et al. Social support as predictor of anxiety and depression in cancer caregivers six months after cancer diagnosis: A longitudinal study. J Clin Nurs 2020;29:996-1002. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chaghazardi M, Janatolmakan M, Rezaeian S, et al. Care burden and associated factors in caregivers of children with cancer. Ital J Pediatr 2022;48:92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yiin JJ, Chen YY, Lee KC. Fatigue and Vigilance-Related Factors in Family Caregivers of Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Cross-sectional Study. Cancer Nurs 2022;45:E621-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finsterer J, Mahjoub SZ. Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:562-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bower JE. Fatigue, brain, behavior, and immunity: summary of the 2012 Named Series on fatigue. Brain Behav Immun 2012;26:1220-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng C, Du N, He L, et al. Factors influencing parental fatigue in children with retinoblastoma based on the unpleasant symptoms theory. Sci Rep 2024;14:17389. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurtovenko K, Fladeboe KM, Galtieri LR, et al. Stress and psychological adjustment in caregivers of children with cancer. Health Psychol 2021;40:295-304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Collins MLZ, Bregman J, Ford JS, et al. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Parents of Patients With Retinoblastoma. Am J Ophthalmol 2019;207:130-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chad-Friedman E, Botdorf M, Riggins T, et al. Parental hostility predicts reduced cortical thickness in males. Dev Sci 2021;24:e13052. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, et al. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol 1989;46:1121-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Syed MJ, Millis SR, Marawar R, et al. Rasch analysis of fatigue severity scale in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2022;130:108688. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buti M, Wedemeyer H, Aleman S, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in chronic hepatitis delta: An exploratory analysis of the phase III MYR301 trial of bulevirtide. J Hepatol 2025;82:28-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouloukaki I, Tsiligianni I, Stathakis G, et al. Sleep Quality and Fatigue during Exam Periods in University Students: Prevalence and Associated Factors. Healthcare (Basel) 2023;11:2389. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dhira TA, Rahman MA, Sarker AR, et al. Validity and reliability of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among university students of Bangladesh. PLoS One 2021;16:e0261590. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care 2003;41:1284-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li H, Li Y, Duan Y, et al. Risk factors for depression in China based on machine learning algorithms: A cross-sectional survey of 264,557 non-manual workers. J Affect Disord 2024;367:617-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keikhaei B, Bahadoram M, Keikha A, et al. Late side effects of cancer treatment in childhood cancer survivors. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2023;29:885-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hossain MB, Haldar Neer AH. Chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Res 2023;185:49-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang MJ, Chang MY, Cheng MY, et al. The Psychological Adaptation Process in Chinese Parent Caregivers of Pediatric Leukemia Patients: A Qualitative Analysis. Cancer Nurs 2022;45:E835-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelazeem B, Abbas KS, Shehata J, et al. Survival trends for patients with retinoblastoma between 2000 and 2018: What has changed? Cancer Med 2023;12:6318-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Callaham S, Ritchie M, Carr M. Parental fatigue before and after ventilation tube insertion in their children. Am J Otolaryngol 2020;41:102741. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kramer N, Nijhof SL, van de Putte EM, et al. Role of parents in fatigue of children with a chronic disease: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Paediatr Open 2021;5:e001055. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng C, Cao W, Zhao T, et al. Hope level and associated factors among parents of retinoblastoma patients during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:391. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toledano-Toledano F, Luna D, Moral de la Rubia J, et al. Psychosocial Factors Predicting Resilience in Family Caregivers of Children with Cancer: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:748. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lundgren J, Thiblin E, Lutvica N, et al. Concerns experienced by parents of children treated for cancer: A qualitative study to inform adaptations to an internet-administered, low-intensity cognitive behavioral therapy intervention. Psychooncology 2023;32:237-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russo E, Spallarossa A, Tasso B, et al. Nanotechnology for pediatric retinoblas-toma therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2022;15:1087. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olbara G, van der Wijk T, Njuguna F, et al. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treatment in an academic hospital in Kenya: Treatment outcomes and health-care providers’ perspectives. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2021;68:e29366. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bilgehan T, Bağrıaçık E, Sönmez M. Factors affecting care burden and life satisfaction among parents of children with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Nurs 2024;77:e394-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Shen N, Zhang X, et al. Care burden and its predictive factors in parents of newly diagnosed children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in academic hospitals in China. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:3703-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perak K, McDonald FEJ, Conti J, et al. Family adjustment and resilience after a parental cancer diagnosis. Support Care Cancer 2024;32:409. [Crossref] [PubMed]