Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients with extremely severe burns: a retrospective study of 101 cases

Highlight box

Key findings

• Extremely severe burns in pediatric patients constitute devastating trauma characterized by high mortality rates and profound physical/psychological sequelae.

What is known and what is new?

• Extremely severe burns in pediatric patients represent a severe form of trauma. However, as a populous nation, China is yet to systematically collect comprehensive epidemiological data on pediatric patients with extremely severe burns.

• In North China, scalds are the predominant cause of extremely severe burns in children. Complications, such as flame burns, wound infections, pneumonia and shock, frequently result in poorer prognoses. It is crucial to prioritize children aged 1 to 3 years in preventive efforts against extremely severe burns.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Enhancing safety education at both the family and community levels is essential to protect children from risk factors. Continuous improvement of emergency response and treatment capabilities for extremely severe burns and their complications is also imperative.

Introduction

Burn injuries represent a severe form of trauma. While the incidence of burns has gradually declined in high-income countries, it remains alarmingly high in other regions, with approximately 90% of burn cases occurring in low- and middle-income countries (1,2). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), as of October 13, 2023, burns are the fifth most common cause of non-fatal injuries in children, resulting in significant social and economic burdens. Furthermore, the mortality rate from burns in children is 7 to 11 times higher in low-income countries compared to high-income countries (3). Statistics indicate that the highest proportion of pediatric burn patients are aged 0 to 5 years (4). Among the various types of burns, scalds or contact with hot substances are the most prevalent, followed by flame burns and chemical burns (5).

Children, as a distinct population, exhibit significant differences from adults in metabolism, physiology, and anatomy (6,7). For instance, children’s skin is thinner, and their blood volume is smaller. When confronted with severe burns, they often require timely and specialized treatment and care. Thus, the management of extremely severe burns poses a major challenge in modern medicine, necessitating collaborative efforts among pediatricians, burn and plastic surgeons, anesthesiologists, pediatric intensive care specialists, and other experts. This multidisciplinary approach addresses critical issues such as early fluid resuscitation, shock management, surgical debridement, skin grafting, and post-burn scar management (8,9).

Children are in a rapid growth and development phase, and while some may achieve initial wound healing during their first hospitalization through dressing changes or surgery, many will require secondary surgical interventions to correct scar contractures and functional impairments resulting from extensive burns. The burn treatment process is extremely painful, and even after successful wound healing, the resultant scars can significantly impact both appearance and function (10). Severe scar contractures may restrict growth and lead to functional impairments in various body parts, further hindering daily activities (11-13). In addition to physical challenges, burns and associated scar issues impose substantial financial and psychological burdens on children and their families, potentially affecting long-term mental health (14-16). These challenges are particularly pronounced for pediatric patients with extremely severe burns.

Thus, conducting epidemiological research on extremely severe burns in pediatric patients is critically important, as it can effectively guide prevention strategies and emergency care for these injuries, yielding positive impacts on both families and society. The Burn and Plastic Surgery Department of Beijing Children’s Hospital is among the earliest specialized units in China dedicated to the treatment of pediatric burns. As the National Center for Children’s Health, our hospital primarily treats pediatric burn patients from Beijing, northern China, and surrounding regions, while also receiving referrals from across the country. We possess extensive experience in the emergency care, treatment, and rehabilitation of pediatric patients with extremely severe burns. However, as a populous nation, China is yet to systematically collect comprehensive epidemiological data on pediatric patients with extremely severe burns. Existing studies are limited to statistics from burn centers across different regions of China, encompassing all burn-related hospitalizations, but lacking specific epidemiological investigations focused on extremely severe burns (17,18).

Conducting a dedicated epidemiological study on pediatric patients with extremely severe burns will provide more accurate data, thereby enhancing the quality of treatment and care for these critically injured patients. Therefore, it is imperative to undertake a retrospective study examining the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients with extremely severe burns treated in large pediatric burn centers in China. This study aims to summarize the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of such patients at our hospital, with the goal of raising awareness among the public and healthcare professionals regarding extremely severe burns in children. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-156/rc).

Methods

Data collection, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital (approval No. 2024-E-172-R) and conducted at the Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery at Beijing Children’s Hospital, a tertiary pediatric hospital in China. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements. Our hospital primarily treats pediatric burn patients from Beijing, northern China, and surrounding areas, while also accepting referrals from across the country. At the National Burn Conference in 1970, experts classified pediatric burns into four categories based on severity: mild burns, moderate burns, severe burns, and extremely severe burns. Extremely severe burns are defined as burns covering more than 25% of total burn surface area (TBSA) or third-degree burns involving more than 10% of TBSA. Furthermore, mild burns are defined as second-degree burns covering less than 5% TBSA. Moderate burns encompass second-degree burns affecting 5–15% TBSA, third-degree burns involving less than 5% TBSA, or second-degree burns occurring in critical anatomical regions including the face, hands, feet, or perineum. Severe burns constitute more extensive injuries, including burns covering 15–25% TBSA, third-degree burns involving 5–10% TBSA, or smaller burns (<15% TBSA) presenting with complicating factors such as systemic compromise/shock, concomitant major trauma or chemical intoxication, significant inhalational injury, or facial burns exceeding 5% TBSA in infants.

This retrospective study summarizes the clinical data of 101 pediatric patients with extremely severe burns who were hospitalized and treated at our burn department between 2013 and 2023. The inclusion criteria were pediatric patients diagnosed with extremely severe burns and treated at our department from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2023. Exclusion criteria included patients with traumatic skin injuries or full-thickness skin defects caused by non-burn-related reasons, as well as those with repeated admissions. Patient records were retrieved from the hospital’s electronic medical record (EMR) system. Two researchers independently reviewed the data, extracted relevant information, and resolved discrepancies through discussion. The following data were extracted from the EMR system: gender, age, place of residence, cause of injury, season of injury and location of injury, time of admission, length of stay (LOS), burn area and depth, wound infection status, TBSA and prognosis. Burn area assessments were conducted using the Rule of Nines and the Palm Rule as applied in China.

Statistical analysis

Data were organized and categorized using Microsoft Excel 2021, and descriptive statistics such as median, mean, and interquartile range (IQR) were calculated. GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software Corporation, USA) and SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) were used for statistical analysis. For continuous data, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied if the data followed a normal distribution; otherwise, the Kruskal-Wallis test was utilized. For categorical data, the Chi-squared test was used if the expected frequency was greater than 5 and the total sample size exceeded 40; otherwise, Fisher’s exact test was applied. A multivariate linear regression analysis was conducted to identify risk factors for LOS, and multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). A VIF value of less than 5 indicated no multicollinearity between variables, ensuring the accuracy of the regression results. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

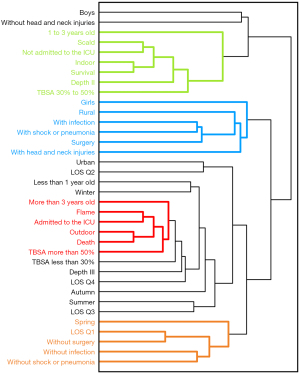

Additionally, 14 categorical variables, including gender, place of residence, age, cause of injury, TBSA, burn depth, season of injury, location of injury, wound infection, prognosis, surgery, and complications, were converted into binary variables. For example, gender was transformed into male (1 = yes, 0 = no) and female (1 = yes, 0 = no). Continuous data for LOS were discretized based on percentiles: LOS shorter than the first quartile (Q1) were classified as Q1 =1; LOS between Q1 and the median were classified as Q2 =1; LOS between the median and the third quartile (Q3) were classified as Q3 =1; and LOS longer than Q3 were classified as Q4 =1. Systematic clustering analysis was performed on the transformed binary variables, with indicators in the same cluster more likely to co-occur, while those in different clusters had a lower likelihood of co-occurrence.

Results

General characteristics

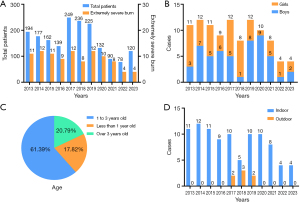

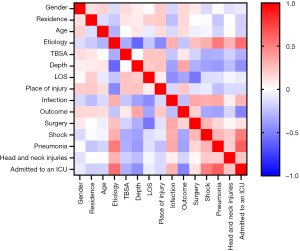

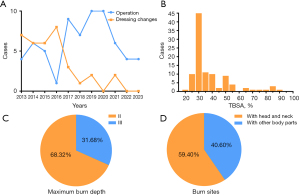

Table 1 summarizes the general characteristics of all pediatric patients with extremely severe burns included in this study. We reviewed the clinical data of 101 patients who were hospitalized and treated for extremely severe burns at the Department of Burn and Plastic Surgery at Beijing Children’s Hospital from January 1, 2013, to December 31, 2023. Figure 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of the 101 pediatric patients, including patient distribution, gender, age, and location of injury. These patients accounted for 5.7% of the total 1,766 burn-related hospitalizations during this period. Over the past 11 years, the number of hospitalizations for extremely severe burns has demonstrated a general downward trend, reaching its lowest point in 2022 and 2023 (Figure 1A). Overall, there was a significant gender difference in the incidence of extremely severe burns over the years, with the highest male-to-female ratio of 1:0.11 recorded in 2020 (Figure 1B). In terms of age distribution, children aged 1 to 3 years represented the largest proportion of cases (61.4%), followed by those under 1 year of age (20.8%) (Figure 1C). Among the 101 patients, 64 patients (63.4%) resided in rural areas, where they were more likely to sustain outdoor injuries, particularly flame burns, and exhibited a higher rate of wound infections (Figure 2). More than half of the patients (52.5%) experienced complications such as shock or pneumonia, and 21 patients (20.8%) required treatment in the intensive care unit (ICU). The LOS ranged from 1 to 117 days, with a median of 24 days (IQR: 14–34 days). The total medical cost ranged from 4,594.96 to 833,198.75 RMB, with a median of 66,845.01 RMB (IQR: 36,443.32–83,823.99 RMB). Between 2013 and 2023, the surgical intervention rate among pediatric patients with extremely severe burns was 65.3%. Of the 101 patients included in this study, there were 8 fatalities, resulting in a mortality rate of 7.9%.

Table 1

| Characteristics | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boys:girls | 1:2.67 | 1:0.71 | 1:1.2 | 1:0.5 | 1:1.4 | 1:7 | 1:0.5 | 1:0.11 | 1:0.6 | 1:3 | 1:1 | 0.049* |

| Age (years) | 0.04* | |||||||||||

| <1 | 1 (9.09) | 4 (33.33) | 3 (27.27) | 2 (22.22) | 5 (41.67) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (37.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| 1–3 | 10 (90.91) | 8 (66.67) | 7 (63.64) | 7 (77.78) | 4 (33.33) | 5 (62.5) | 9 (75.0) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | |

| 4–18 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 0 (0) | 3 (25.00) | 2 (25.0) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (40.0) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | |

| TBSA (%) | 0.41 | |||||||||||

| 25–30 | 1 (9.09) | 1 (8.33) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (11.11) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 3 (25.0) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| 31–50 | 7 (63.64) | 8 (66.67) | 9 (81.82) | 8 (88.89) | 9 (75.0) | 3 (37.5) | 7 (58.33) | 6 (60.0) | 6 (75.0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| 51–100 | 3 (27.27) | 3 (25) | 1 (9.09) | 0 (0) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (50) | 2 (16.67) | 3 (30.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Burn depth | 0.12 | |||||||||||

| II | 10 (90.91) | 10 (83.33) | 9 (81.82) | 8 (88.89) | 7 (58.33) | 3 (37.5) | 8 (66.67) | 6 (60.0) | 5 (62.5) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| III | 1 (9.09) | 2 (16.67) | 2 (18.18) | 1 (11.11) | 5 (41.67) | 5 (62.5) | 4 (33.33) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Place of injury | 0.04* | |||||||||||

| Indoor | 11 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 11 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | 10 (83.33) | 5 (62.5) | 10 (83.33) | 10 (100.0) | 8 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Outdoor | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (16.67) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (16.67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Infection | 0.33 | |||||||||||

| With | 6 (54.55) | 5 (41.67) | 5 (45.45) | 5 (55.56) | 11 (91.67) | 6 (75.0) | 7 (58.33) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Without | 5 (45.45) | 7 (58.33) | 6 (54.55) | 4 (44.44) | 1 (8.33) | 2 (25.0) | 5 (41.67) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Shock | 0.24 | |||||||||||

| With | 5 (45.45) | 3 (25.0) | 4 (36.36) | 1 (11.11) | 5 (41.67) | 6 (75.0) | 4 (33.33) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (50.0) | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Without | 6 (54.55) | 9 (75.0) | 7 (63.64) | 8 (88.89) | 7 (58.33) | 2 (25.0) | 8 (66.67) | 4 (40.0) | 4 (50.0) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Pneumonia | 0.52 | |||||||||||

| With | 3 (27.27) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (18.18) | 2 (22.22) | 4 (33.33) | 4 (50.0) | 5 (41.67) | 5 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (25.0) | |

| Without | 8 (72.73) | 9 (75.0) | 9 (81.82) | 7 (77.78) | 8 (66.67) | 4 (50.0) | 7 (58.33) | 5 (50.0) | 8 (100.0) | 3 (75.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Surgery | <0.001*** | |||||||||||

| With | 4 (36.36) | 6 (50.0) | 5 (45.45) | 1 (11.11) | 9 (75) | 7 (87.5) | 10 (83.33) | 10 (100.0) | 6 (75.0) | 4 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | |

| Without | 7 (63.64) | 6 (50.0) | 6 (54.55) | 8 (88.89) | 3 (25) | 1 (12.5) | 2 (16.67) | 0 (0) | 2 (25.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Outcome | 0.89 | |||||||||||

| Survival | 10 (90.91) | 12 (100.0) | 10 (90.91) | 8 (88.89) | 11 (91.67) | 7 (87.5) | 11 (91.67) | 10 (100.0) | 7 (87.5) | 4 (100.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Death | 1 (9.09) | 0 (0) | 1 (9.09) | 1 (11.11) | 1 (8.33) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (8.33) | 0 (0) | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 1 (25.0) | |

Data are presented as n (%). *, P<0.05; ***, P<0.001. TBSA, total burn surface area.

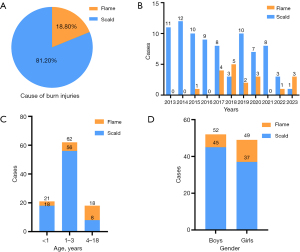

Location and cause of injury

There was a statistically significant difference (P=0.04) in the incidence of extremely severe burns among patients based on the location of injury (Figure 1D). The majority of injuries occurred indoors (93.1%), while only 6.9% occurred outdoors. With the exception of the years 2017, 2018, and 2019, all children who sustained extremely severe burns in the other eight years were injured indoors. Among the 101 cases of pediatric extremely severe burns, two causes were identified: scalds from hot liquids accounted for 81.2% of cases, while flame burns represented 18.8% (Figure 3A). Over the past 11 years, the difference in incidence between scalds and flame burns was statistically significant (P<0.001) (Figure 3B). Most extremely severe burns were caused by contact with hot liquids, such as boiling water or porridge. All scald injuries occurred indoors, while all outdoor extremely severe burns were exclusively due to flame injuries. In infancy and early childhood, scalds were the primary cause of extremely severe burns, however, as children entered preschool age, more than half of the extremely severe burns were attributed to flame injuries (Figure 3C). The difference in the incidence of scalds versus flame burns across different age groups was statistically significant (P=0.002). In the 101 cases analyzed, the proportion of male children with flame burns (13.5%) was lower than that of female children (24.5%) (Figure 3D).

Treatment of Injury

It is evident that prior to 2017, the primary treatment modality for children with extremely severe burns admitted to our hospital was wound dressing changes. However, with advances in medical practice and evolving parental attitudes, an increasing number of parents are now opting for surgical interventions, such as debridement and skin grafting (Figure 4A). In cases of pediatric extremely severe burns, the decision to perform debridement and skin grafting is influenced by the cause and depth of the burn, and the presence of shock upon admission. Notably, extremely severe burns caused by flame injuries were more frequently treated surgically (P=0.01). Furthermore, the proportion of children undergoing surgery increased significantly with burn depth (P=0.001). Additionally, children presenting with shock at the time of admission were more likely to require surgical intervention (P=0.005) (Figure 2).

Severity of burns

Figure 4B illustrates that the median TBSA was 30% (IQR: 30–40%), with 11.9% of patients having a TBSA between 20% and 29%, and 66.3% having a TBSA between 30% and 49%. As shown in Figure 4C, among the 101 pediatric patients in this study, 31.68% had third-degree burns, representing the deepest burn depth observed. Among these 32 pediatric cases, 20 patients exhibited exclusively third-degree burns, with 6 mortality cases observed. The remaining 12 patients presented predominantly with third-degree burns accompanied by deep second-degree burns, among which 1 mortality case occurred. Of the 69 patients with second-degree burns, 41 cases involved exclusively deep second-degree burns, including the remaining single mortality case. Notably, only 28 patients in the entire study cohort demonstrated predominantly deep second-degree burns with concomitant superficial second-degree burns, all of whom showed favorable prognosis. Burns involving the head and neck are particularly significant in pediatric burn injuries due to their association with a high risk of shock and respiratory inhalation injuries. In this study, over half (59.4%) of the patients sustained extensive burns involving these areas (Figure 4D). There were statistically significant differences in TBSA based on location and cause of injury, presence of wound infection, and the occurrence of shock or pneumonia. Flame burns resulted in a higher TBSA compared to scald burns (P<0.001), and outdoor injuries were associated with a higher TBSA than indoor injuries (P=0.02). Additionally, as TBSA increased, the likelihood of wound infection, shock, or pneumonia also increased (P=0.02, P=0.001, P=0.001) (Figure 2).

Factors affecting LOS

Table 2 summarizes the LOS for the pediatric patients in this study. We observed statistically significant differences in the median LOS based on factors such as the presence of wound infection and surgical treatment (P<0.001) (Figure 2). To further investigate, we applied multivariate linear regression analysis to identify risk factors associated with LOS (Table 3). Among the various risk factors, prognosis had the greatest impact on prolonged LOS (standardized coefficient =0.418, P<0.001). Patients with a poor prognosis often experienced rapid deterioration and death shortly after admission. Wound infection was identified as the second most influential factor (standardized coefficient =0.358, P<0.001). Additionally, our etiological analysis revealed that patients with scald injuries generally had a shorter LOS compared to those with flame burns.

Table 2

| Factors related to LOS | LOS (days), median [IQR] |

P value |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.78 | |

| Boys, n=52 | 22 [15–34] | |

| Girls, n=49 | 24 [14–34] | |

| Age, years | 0.03* | |

| <1, n=21 | 32 [23–36] | |

| 1–3, n=62 | 20 [12–30] | |

| 4–18, n=18 | 27 [17–41] | |

| Place of residence | 0.06 | |

| Urban, n=37 | 20 [14–27] | |

| Rural, n=64 | 27 [16–36] | |

| Place of injury | 0.50 | |

| Indoor, n=94 | 24 [14–34] | |

| Outdoor, n=7 | 26 [17–53] | |

| Cause of injury | 0.03* | |

| Flame, n=19 | 27 [20–63] | |

| Scald, n=82 | 23 [14–33] | |

| TBSA (%) | 0.007** | |

| 25–30, n=12 | 27 [13–36] | |

| 31–50, n=67 | 21 [13–30] | |

| 51–100, n=22 | 34 [24–56] | |

| Burn depth | 0.04* | |

| II, n=69 | 23 [14–32] | |

| III, n=32 | 29 [19–40] | |

| Infection | <0.001*** | |

| With, n=58 | 32 [20–39] | |

| Without, n=43 | 17 [11–25] | |

| Shock | 0.50 | |

| With, n=42 | 26 [17–35] | |

| Without, n=59 | 20 [14–33] | |

| Pneumonia | 0.81 | |

| With, n=30 | 26 [17–41] | |

| Without, n=71 | 23 [14–33] | |

| Surgery | <0.001*** | |

| With, n=66 | 28 [20–37] | |

| Without, n=35 | 12 [8–22] | |

| Outcome | 0.02* | |

| Survival, n=93 | 25 [17–34] | |

| Death, n=8 | 5 [2–15] |

*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. IQR, interquartile range; LOS, length of stay; TBSA, total burn surface area.

Table 3

| Factors related to LOS | Unstandardized beta coefficients | Standardized beta coefficients | T | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With surgery | 7.456 | 0.189 | 2.231 | 0.03* |

| With infection | 13.605 | 0.358 | 4.190 | <0.001*** |

| With scald | −14.681 | −0.305 | −3.746 | <0.001*** |

| Better outcomes | 29.082 | 0.418 | 5.070 | <0.001*** |

*, P<0.05; ***, P<0.001. LOS, length of stay.

Complications and prognosis

As shown in Figure 2, factors such as burn depth, location and cause of injury, wound infection, and the presence of complications like shock or pneumonia significantly influence prognosis. With increasing burn depth and the presence of wound infection, pneumonia, or shock, prognosis tends to worsen. However, gender, age, and TBSA did not demonstrate a significant correlation with prognosis. In this study, our analysis of 101 pediatric patients with extremely severe burns revealed distinct treatment pathways. The majority of cases (n=81, 80.2%) presented directly to our tertiary care center as the initial treatment facility, while the remaining 20 cases (19.8%) were transferred from primary care hospitals following initial assessment. Notably, all patients received immediate fluid resuscitation upon admission to our institution. The resuscitation protocols differed slightly between groups: 96 patients (95.0%) received combined crystalloid and colloid volume expansion, whereas 5 referred cases (5.0%, all from peripheral hospitals) had received crystalloid-only resuscitation prior to transfer. Furthermore, microbiological analysis of the 58 pediatric patients with infected extremely severe burns revealed universal wound swab culture positivity (58/58, 100%), with concurrent bacteremia documented in 24 cases (41.4%). The predominant wound colonizers were Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n=22, 37.9%), Acinetobacter baumannii (n=21, 36.2%), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (n=20, 34.5%), while bloodstream isolates were dominated by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus spp. (n=8, 33.3%), Acinetobacter baumannii (n=7, 29.2%), and Klebsiella pneumoniae (n=6, 25.0%). Antimicrobial therapy was systematically optimized through susceptibility-directed escalation to target these multidrug-resistant pathogens. Finally, our analysis identified 23 cases (22.8%) with confirmed inhalational injury, among which 5 fatalities occurred (21.7% mortality rate). The presence of inhalational injury demonstrated statistically significant association with poorer prognosis in pediatric patients with extremely severe burns (P=0.01). The cure rate was highest in the 0 to1 year age group, reaching 100%, while it was lowest in the group over 3 years old, at 88.9%. In this study, 8 out of 101 children died. Table 4 provides detailed information on the eight deceased patients, which included 2 boys and 6 girls, with scalds and flame burns each accounting for four cases. Seven patients had head and neck injuries, and three patients underwent surgical treatment, with the number of surgeries being 1, 2, and 5, respectively. Furthermore, our longitudinal follow-up of 93 surviving cases (with 2 lost to follow-up: one foreign national contactable only through embassy channels, and one case with changed contact information) revealed universal scar formation in all 91 evaluable patients. Notably, 70 cases (76.9%) developed joint-involving scars with functional impairment, while 79 patients (86.8%) exhibited psychological trauma due to socially visible facial/scalp scarring. Seventy children (76.9%) required readmission for surgical scar revision, highlighting the substantial long-term morbidity associated with pediatric patients with extremely severe burns despite survival. To further characterize the clinical profile of pediatric patients with extremely severe burns, we conducted a comparative analysis with contemporaneous severe burn cases from our institutional database (Table 5). Integrated with longitudinal follow-up data, this analysis clearly demonstrates that extremely severe burn cases were associated with significantly prolonged LOS, higher surgical intervention rates, and increased likelihood of adverse outcomes.

Table 4

| Patient ID | Age (years) | Gender | Etiology | TBSA% | Surgery number | Head and neck injuries | LOS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 1 | Girl | Scald | 25 | 0 | Without | 1 |

| Case 2 | 2 | Boy | Scald | 85 | 1 | With | 18 |

| Case 3 | 1 | Girl | Scald | 20 | 0 | With | 3 |

| Case 4 | 1 | Boy | Flame | 85 | 0 | With | 6 |

| Case 5 | 3 | Girl | Flame | 66 | 2 | With | 12 |

| Case 6 | 4 | Girl | Flame | 45 | 0 | With | 4 |

| Case 7 | 2 | Girl | Scald | 40 | 0 | With | 1 |

| Case 8 | 4 | Girl | Flame | 90 | 5 | With | 24 |

LOS, length of stay; TBSA, total burn surface area.

Table 5

| Characteristic | Extremely severe burns | Severe burns |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 52 | 290 |

| Female | 49 | 201 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <1 | 21 | 121 |

| 1–3 | 62 | 289 |

| 4–18 | 18 | 81 |

| TBSA (%) | 30 [30–40] | 15 [15–20] |

| LOS (days) | 24 [14–34] | 12 [9–19] |

| Cause of injury | ||

| Flame | 19 | 12 |

| Scald | 82 | 479 |

| Surgery | ||

| With | 66 | 182 |

| Without | 35 | 309 |

| Outcome | ||

| Survival | 93 | 491 |

| Death | 8 | 0 |

| Total | 101 | 491 |

Data are presented as number or median [interquartile range]. LOS, length of stay; TBSA, total burn surface area.

Delayed treatment

In accordance with prior research establishing 7 hours as the cutoff for delayed treatment (19), we adopted this criterion to define delayed treatment as initial medical presentation exceeding 7 hours post-injury. Among 101 pediatric patients with extremely severe burns in our study, 13 cases (12.9%) met criteria for delayed treatment. Notably, all 8 mortality cases occurred exclusively in the early treatment group (<7 hours post-injury), while no deaths were observed in the delayed treatment cohort. Furthermore, no statistically significant differences were identified between delayed and early treatment groups regarding residential distribution (urban vs rural, P=0.56) or infection incidence rates (P=0.75), etc.

Systematic clustering

In this study, we aimed to gain a more direct understanding of the similarities between various factors by transforming 14 variables—including gender, residence, age, cause of injury, TBSA, burn depth, season of injury, location of injury, wound infection, prognosis, surgical intervention, and complications—into binary variables. Additionally, LOS was discretized into binary variables based on percentiles. Systematic clustering of these transformed binary variables yielded satisfactory clustering results (Figure 5). The clustering analysis indicates that children aged more than 3 years old with a TBSA greater than 50% are typically injured outdoors by flame burns, often requiring transfer to the ICU, with generally poor prognoses.

Discussion

Children, as a vulnerable population, are in a critical phase of growth and development. Their innate curiosity about their surroundings, combined with limited awareness of potential dangers and insufficient supervision from caregivers, places them at high risk for accidental injuries. Extremely severe burns in children can progress rapidly and pose significant threats, often resulting in permanent physical and psychological harm, disability, or even death. However, both in China and globally, there is a notable lack of epidemiological studies specifically focusing on pediatric extremely severe burns. Therefore, this study aims to summarize the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of pediatric patients with extremely severe burns treated at our center. By doing so, we seek to raise awareness among the public and healthcare professionals about the severity of these injuries and enhance the capacity for prevention and effective treatment of such life-threatening incidents.

In this study, we classified the pediatric patients into three age groups: less than 1 year, 1 to 3 years, and older than 3 years. Our findings revealed that children aged 1 to 3 years accounted for the highest proportion of extremely severe burns (61.4%). This result aligns with previous statistics on burns of all severities (17). The proportions in the other two groups were significantly lower. Infants are generally restricted in their activities, while preschool-aged children tend to have developed a degree of self-protection and risk assessment abilities. However, children aged 1 to 3 years are in a developmental stage characterized by independent movement and a strong desire to explore their environments, yet they have not fully developed risk-avoidance awareness. Inadequate supervision and protection during this stage increase the likelihood of these children sustaining burn or scald injuries. Due to work-related factors, parents of children in this age group are often not present, leaving daily care primarily to the hands of grandparents. Some elderly caregivers may lack adequate safety awareness and may have diminished emergency response capabilities, contributing to accidental injuries. Additionally, some parents exhibit low levels of responsibility and education, resulting in insufficient supervision, which can lead to severe and irreversible consequences when children are left to roam unsupervised (20). Extremely severe burn rates are higher in rural areas compared to urban regions, where children are more likely to sustain outdoor injuries, be susceptible to flame burns, and face higher risks of wound infection. This issue warrants greater attention. Therefore, community organizations should regularly provide safety education and injury prevention training to caregivers and family members. In rural areas, these efforts should be intensified to raise awareness among residents. Relevant authorities should organize personnel to conduct fire safety risk assessments in rural households to mitigate the risk of severe accidental injuries among children.

The cause of burns is diverse, encompassing scalds, flame burns, electrical injuries, and chemical burns. In this study, the causes of burns in 101 pediatric patients primarily included scalds and flame burns. Notably, 81.2% of the extremely severe burns were caused by scalds, while the remaining 18.8% were attributed to flame burns. All 101 patients with extremely severe burns were under the age of 10. According to 2022 statistics on burn patients in mainland China (21), scalds accounted for the majority (88.68%) of burn injuries in children aged 0 to 10 years, whereas flame burns were less common, representing only 4.89%. This is significantly lower than the 18.8% observed in our study, suggesting a closer association between flame burns and extremely severe burns. Our findings indicate that the proportion of flame burns increased with age, rising from 14.3% in infancy and toddlerhood to 55.6% in older children. Therefore, we advocate for personalized prevention strategies targeting different types of burns, particularly scalds. Many severe or extensive scald injuries in this study occurred when children came into contact with containers holding hot liquids positioned above their height. In such cases, the hot liquid often cascaded downward, causing widespread burns. More critically, the downward flow of the hot liquid frequently affected the head and neck, increasing the likelihood of respiratory or gastrointestinal burns and exacerbating the severity of the injury. The findings observed in this study are consistent with the conclusions of previous research on pediatric burns caused by negligence (22). A minority of children sustained burns after falling into pots of boiling water or containers of hot liquid, with almost all incidents occurring in rural household. To prevent such incidents, it is essential to eliminate potential hazards that may cause scalds, keep them out of children’s reach, or implement protective measures. Furthermore, children should not be allowed near heaters or kitchens. In the event of an accident, the immediate application of appropriate first aid is crucial. Recent study indicate that over half of pediatric burn patients (56.6%) in their cohort did not receive any first aid following the injury (23). Although 27.5% of patients underwent cooling measures, such as cold water or cool towels, only 1.8% received the gold standard of care—applying cool water to the burn area for at least 20 minutes. Multivariate linear regression analysis showed that the application of cooling measures during first aid was associated with reductions in the number of surgeries, total operative time per TBSA, cost per TBSA, and LOS per TBSA. Therefore, hospitals and other professional institutions should regularly promote such first aid knowledge to the public, thereby improving the prevention and emergency management of extremely severe burns at the community level (24). Furthermore, with the advancement of technology, telehealth has increasingly come into public focus, playing a crucial role in the diagnosis of critical illnesses and emergency management (25). Individuals, families, and even community hospitals should become proficient in utilizing telehealth, effectively allocating medical resources, and ensuring appropriate pre-hospital emergency care for pediatric patients with extremely severe burns.

For children with extremely severe burns, debridement and skin grafting are effective methods for removing necrotic tissue and promoting wound healing. The findings of this study indicate that in recent years, surgical intervention has increasingly replaced traditional wound dressing changes, establishing itself as the primary treatment approach for extremely severe burns in pediatric patients. Among the 101 children studied, those with flame burn injuries, deeper burn depth, or who presented in shock upon admission were at a higher risk for requiring surgical intervention. Research demonstrates that timely removal of necrotic tissue can reduce hospitalization costs, shorten healing times, and yield more favorable outcomes (26). However, recent study have shown that the mortality risk for children undergoing debridement and skin grafting within three days of hospitalization is significantly higher than for those who receive intervention at a later time (27). For pediatric patients, especially those under five years of age, delaying surgical intervention by 72 hours may be beneficial for survival. Thus, determining the optimal timing for surgical intervention in extremely severe burns in pediatric patients is crucial for improving outcomes. Clinicians should gain experience through daily practice and continue to investigate this important issue.

The clinical treatment outcomes for children with extremely severe burns are influenced by a variety of factors. Many children with extremely severe burns, even if they survive, face long-term scar management. Mortality rate is a crucial indicator of treatment efficacy for extremely severe burns. The results of this study indicate that mortality rates are not significantly associated with age or gender, however, factors such as burn depth, cause and location of injury, wound infection, and the presence of shock or pneumonia significantly impact prognosis. Consistent with previous research findings, we observed that flame burns are a significant risk factor influencing prognosis (28). There is a statistically significant difference in hospitalization duration between deceased and surviving cases, as those who succumb often experience rapid disease progression, severe infections, shock, or irreversible organ failure, leading to death shortly after admission. Key factors influencing hospitalization duration include prognosis and wound infection, along with cause of injury, burn area and depth, the frequency of surgical interventions, and complications such as shock or pneumonia. These findings are consistent with observations from other burn centers (29,30). Burn shock, resulting from various causes, is a critical component of the disease course following extremely severe burns. It is classified as mixed shock, with pathophysiological mechanisms involving thermal injury to local cellular tissues, leading to morphological, functional, and metabolic damage, which results in fluid loss or redistribution. This also includes systemic damage mediated by neuroendocrine factors, cytokines, and other inflammatory mediators (31-33). Shock due to burns, occurring within 1 to 3 days post-injury, represents a significant aspect of the disease trajectory and is among the leading causes of early complications and mortality. Therefore, standardized prevention and treatment of shock are vital for managing extremely severe burns. To address pediatric burn shock, we convened experts in the relevant fields to discuss this issue, resulting in the development of the “Expert Consensus on Fluid Resuscitation of Early Pediatric Burn Shock (Version 2023)” (34) which provides recommendations on nine clinical issues, including the calculation of burn area and fluid resuscitation formulas, thereby offering a basis and guidance for clinical practice.

Our study revealed a noteworthy finding that challenges conventional clinical assumptions. While prevailing medical wisdom suggests that delayed burn treatment adversely affects prognosis and increases complication rates, delayed treatment often attributed to patients’ geographic location and our data demonstrated that all 8 mortality cases occurred in the early treatment group (<7 hours post-injury), with no significant differences observed between delayed and immediate treatment groups regarding residential distribution or infection rates. This apparent paradox may be explained by two key factors, substantial improvements in China’s medical transport infrastructure have enabled prompt treatment or rapid transfer to tertiary care centers for pediatric trauma patients, significantly reducing the impact of geographic barriers on treatment timing; and the inherent severity of extreme burns (e.g., large-surface flame injuries) often causes catastrophic physiological derangement at onset, which may diminish the relative contribution of treatment timing to overall outcomes in these critically ill children.

Systematic clustering can categorize numerous indicators into different groups, where the likelihood of indicators co-occurring within the same group is relatively high, while the likelihood of co-occurrence between different groups is lower. In the context of epidemiological statistics, this method provides a convenient and efficient means to analyze the co-occurrence probabilities of various indicators, thus guiding and informing subsequent research directions.

However, this study is limited to a single-center analysis, reflecting only the epidemiological data of extremely severe burns in pediatric patients in North China. To enhance our understanding and applicability, it is essential to broaden the research scope to include data from across China and even globally, facilitating the development of comprehensive diagnostic and treatment consensus guidelines.

Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of extremely severe burns in pediatric patients treated at the Burn and Plastic Surgery Department of Beijing Children’s Hospital, affiliated with Capital Medical University, from 2013 to 2023. The findings of this study lead to the following main conclusions: In North China, scalds are the predominant cause of extremely severe burns in children. Complications, such as flame burns, wound infections, pneumonia and shock, frequently result in poorer prognoses. It is crucial to prioritize children aged 1 to 3 years in preventive efforts against extremely severe burns. Additionally, enhancing safety education at both the family and community levels is essential to protect children from risk factors. Continuous improvement of emergency response and treatment capabilities for extremely severe burns and their complications is also imperative.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate Professor Yunsheng Chen from Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine, and Professor Tuo Liu from The National Institute for Occupational Health and Poison Control, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (NIOHP, China CDC), for their invaluable assistance in the implementation and statistical analysis of this study.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-156/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-156/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-156/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-156/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Children’s Hospital (approval No. 2024-E-172-R). Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Smolle C, Cambiaso-Daniel J, Forbes AA, et al. Recent trends in burn epidemiology worldwide: A systematic review. Burns 2017;43:249-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh DG. Management of Burns. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2349-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peck M, Pressman MA. The correlation between burn mortality rates from fire and flame and economic status of countries. Burns 2013;39:1054-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santos JV, Oliveira A, Costa-Pereira A, et al. Burden of burns in Portugal, 2000-2013: A clinical and economic analysis of 26,447 hospitalisations. Burns 2016;42:891-900. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah AR, Liao LF. Pediatric Burn Care: Unique Considerations in Management. Clin Plast Surg 2017;44:603-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palmieri TL. Children are not little adults: blood transfusion in children with burn injury. Burns Trauma 2017;5:24.

- Bührer G, Beier JP, Horch RE, et al. Surgical treatment of burns : Special aspects of pediatric burns. Hautarzt 2017;68:385-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baalaaji M. Pediatric Burns-Time to Collaborate Together. Indian J Crit Care Med 2023;27:873-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhu Z, Kong W, Lu Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of paediatric inpatients for scars: A retrospective study. Burns 2023;49:1719-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Obaidi N, Keenan C, Chan RK. Burn Scar Management and Reconstructive Surgery. Surg Clin North Am 2023;103:515-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oosterwijk AM, Mouton LJ, Schouten H, et al. Prevalence of scar contractures after burn: A systematic review. Burns 2017;43:41-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bryarly J, Kowalske K. Long-Term Outcomes in Burn Patients. Surg Clin North Am 2023;103:505-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schouten HJ, Nieuwenhuis MK, van Baar ME, et al. The degree of joint range of motion limitations after burn injuries during recovery. Burns 2022;48:309-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hendriks TCC, Botman M, de Haas LEM, et al. Burn scar contracture release surgery effectively improves functional range of motion, disability and quality of life: A pre/post cohort study with long-term follow-up in a Low- and Middle-Income Country. Burns 2021;47:1285-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones S, Tyson S, Yorke J, et al. The impact of injury: The experiences of children and families after a child’s traumatic injury. Clin Rehabil 2021;35:614-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ayhan H, Savsar A, Yilmaz Sahin S, et al. Investigation of the relationship between social appearance anxiety and perceived social support in patients with burns. Burns 2022;48:816-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han D, Wei Y, Li Y, et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of 5,569 Pediatric Burns in Central China From 2013 to 2019. Front Public Health 2022;10:751615. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li H, Wang S, Tan J, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric burns in southwest China from 2011 to 2015. Burns 2017;43:1306-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang R, Li Y, Xian S, et al. Delayed admission to hospital with proper prehospital treatments prevents severely burned patients from sepsis in China: A retrospective study. Burns 2024;50:1977-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mashreky SR, Rahman A, Chowdhury SM, et al. Perceptions of rural people about childhood burns and their prevention: a basis for developing a childhood burn prevention programme in Bangladesh. Public Health 2009;123:568-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Tian G, Liu J, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of burns in mainland China from 2009 to 2018. Burns Trauma 2022;10:tkac039. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loos MHJ, Meij-de Vries A, Nagtegaal M, et al. Child abuse and neglect in paediatric burns: The majority is caused by neglect and thus preventable. Burns 2022;48:688-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu T, Qu Y, Chai J, et al. Epidemiology and first aid measures in pediatric burn patients in northern China during 2016-2020: A single-center retrospective study. Health Sci Rep 2024;7:e2218. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D’cunha A, Rebekah G, Mathai J, et al. Understanding burn injuries in children-A step toward prevention and prompt first aid. Burns 2022;48:762-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayavi-Haghighi MH, Alipour J. Applications, opportunities, and challenges in using Telehealth for burn injury management: A systematic review. Burns 2023;49:1237-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vivó C, Galeiras R, del Caz MD. Initial evaluation and management of the critical burn patient. Med Intensiva 2016;40:49-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis D, An S, Kayange L, et al. The Timing of Operative Intervention for Pediatric Burn Patients in Malawi. World J Surg 2023;47:3093-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Purcell LN, Banda W, Akinkuotu A, et al. Characteristics and predictors of mortality in-hospital mortality following burn injury in infants in a resource-limited setting. Burns 2022;48:602-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coughlin MC, Ridelman E, Ray MA, et al. Factors associated with an extended length of stay in the pediatric burn patient. Surgery 2023;173:774-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sari H, Akkoc MF, Kilinç Z, et al. Investigation of morbidity, length of stay, and healthcare costs of inpatient paediatric burns. Int Wound J 2024;21:e14385. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rae L, Fidler P, Gibran N. The Physiologic Basis of Burn Shock and the Need for Aggressive Fluid Resuscitation. Crit Care Clin 2016;32:491-505. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeschke MG, van Baar ME, Choudhry MA, et al. Burn injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nielson CB, Duethman NC, Howard JM, et al. Burns: Pathophysiology of Systemic Complications and Current Management. J Burn Care Res 2017;38:e469-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pediatric Burn Study Group. Expert consensus on fluid resuscitation of early pediatric burn shock (version 2023). Chinese Journal of Injury Repair and Wound Healing 2023;18:371-6. (Electronic Edition).