Effects of genetic factors and visual behaviors on interventions for myopia prevention and control in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Highlight box

Key findings

• Children with high genetic myopia risk show a more significant response to interventions, highlighting the importance of early identification and targeted measures. Health education and outdoor activities are most effective, with a 12% reduction in myopia incidence. Compliance is critical for consistent intervention effects, providing a basis for layered strategies.

What is known and what is new?

• Genetic factors and visual behaviors (e.g., parental myopia, prolonged near work) influence childhood myopia, but interventions for different risk groups were unclear.

• This study reveals interactions between genetic susceptibility and behaviors: high-risk children benefit more from outdoor activities, health education, and improved reading posture. Compliance directly determines intervention efficacy.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Prioritize personalized strategies based on genetic risk, enhance compliance, and intensify health education and outdoor activities to optimize control.

Introduction

Childhood myopia is an important public health problem worldwide. In East Asian countries such as China, the incidence of myopia is increasing rapidly (1). According to a report from the World Health Organization, by 2050, the global number of people with myopia will reach 4.9 billion, and the number of those with severe myopia will exceed 900 million (2). Myopia not only affects the quality of life of children but may also lead to severe complications, such as retinal detachment and myopic degeneration, with far-reaching personal and socioeconomic impact. Therefore, it is critical to identify the means to effectively prevent myopia in children (3). The development of myopia is the result of many factors, among which the interaction between genetic factors and environmental factors is central. A study has shown that parental myopia significantly increases the risk of myopia in children, and genetic susceptibility affects refractive development (4). However, heredity is not the sole determinant. Visual behavior, such as long-term near vision use, minimal outdoor activities, and excessive use of electronic screens, has also been confirmed to be an important environmental factor for the occurrence and progression of myopia. When considered against the background of the increasing popularity of digital education, the threat of visual behavior to children’s visual health is becoming increasingly significant (5). Childhood intervention plays an indispensable role in the prevention and control of myopia in children. Comprehensive measures, including health education, behavioral intervention, and scientific correction (scientific correction includes vision testing, refractive correction, amblyopia training, strabismus correction, visual behavior intervention, and more), can effectively slow the progression of myopia. However, the research on the influence of genetic factors and visual behavior on the effect of childhood interventions remain insufficient, and there is a lack of comprehensive, systematic evaluations and quantitative analyses (6,7). Previous studies in this field have mostly focused on a single factor or were limited to a specific region, lacked an analysis of the interaction of genetics and environment on intervention success, or failed to fully validate the targeted effects of different childhood interventions on children's eye correction (4,5). Therefore, in this study, the synergy or interaction between genetic factors and visual behavior in myopia prevention and control care was systematically evaluated through a meta-analysis in order to inform the development of more accurate and scientific care strategies for the prevention and control of children’s myopia and to promote the development of personalized intervention. This study aims to systematically evaluate the interaction between genetic factors, visual behaviors, and specific myopia control interventions (including orthokeratology, soft multifocal lenses, low-concentration atropine, and behavioral counseling) in childhood myopia progression. By quantifying the efficacy of these interventions and their interplay with genetic risk factors, this meta-analysis seeks to optimize evidence-based recommendations for personalized prevention strategies. We present this article in accordance with the MOOSE reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-409/rc).

Methods

Study inclusion

Meta-analysis was employed to quantify the generalizable effects of interventions, consistent with its role in synthesizing results from multiple studies. This approach focuses on aggregating outcomes rather than dissecting specific attributes of individual interventions. A comprehensive analysis of the literature on the effects of genetic factors and visual behavior on the effectiveness of childhood interventions for the prevention and control of myopia in children was conducted via a rigorous systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. Research data were obtained from the PubMed and Web of Science. The retrieval period was from January 2000 to January 2024, and the language was limited to English. Example PubMed search strategy: ((“myopia/prevention and control”[Mesh]) AND (“genetic predisposition”[Mesh] OR “family history”[tiab])) AND (“visual behavior”[tiab] OR “near work”[tiab] OR “outdoor activity”[tiab]) AND (“child”[Mesh] OR “adolescent”[Mesh]). Filters: English, 2000/01/01-2024/01/01. In addition, the reference list of the included studies was manually screened to determine the supplementary relevant literature. The strategy of manual search was the same as above, and the English literature was searched. As part of “other research identification methods”, manual reference validation involves systematically checking the reference list of all 210 articles that entered the full-text evaluation stage after database retrieval, and further screening of 210 articles after manual screening as a supplement to the included literatures. Two researchers screened independently. The inclusion criteria of this study were determined by reading the title and abstract of the literature. The research object was children aged 6–18 years, focusing on the interaction between myopia intervention and genetic factors, and it was an intervention study. A consensus was reached through the discussion between the two people about the differences arising in the screening process. The inclusion criteria for the literature were as follows: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, and case–control studies (all included designs were selected based on their capacity to address causality and minimize confounding); a focus on children or adolescents aged 6 to 18 years, with a clear distinction made between a genetically high-risk population (defined as uncorrected visual acuity ≤0.8 or refractive error ≤−0.50 D) or a gene mutation associated with myopia (identified via targeted gene sequencing or genome-wide association studies) and the general population; a focus on childhood interventions, including health education, behavior adjustment, outdoor activity, and personalized correction (such as rimmed glasses or orthokeratology). Childhood interventions for myopia control were defined as clinically and research-confirmed strategies to delay myopia progression, including optical interventions (e.g., orthokeratology lenses, multifocal glasses) and behavioral interventions (e.g., outdoor activity promotion, near-work time management). These interventions were selected based on their inclusion in systematic reviews and guidelines (2,3,8); clear and detailed reporting of the intervention content and frequency; at least one of the following outcome indicators: (I) myopia incidence (proportion of newly diagnosed myopia cases); (II) change in refractive power [diopter change in spherical equivalent during follow-up]; (III) change in axial length [ocular axial length change in millimeters (mm)]; and follow-up data provided for at least 6 months. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a lack of key variables (such as genetic factors, visual behavior, or information specific to childhood interventions) or outcome indicators, a focus on other ocular conditions (such as cataracts and glaucoma) or systemic conditions (such as diabetes), and a high risk of bias as indicated by the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. If the data were from duplicate analyses or secondary reports, duplicate contents were excluded. Childhood interventions for myopia control were defined as clinically and research-confirmed strategies to delay myopia progression, including optical interventions (e.g., orthokeratology lenses, multifocal glasses) and behavioral interventions (e.g., outdoor activity promotion, near-work time management). These interventions were selected based on their inclusion in systematic reviews and guidelines.

Literature retrieval strategies

The relevant literature was obtained via a systematic search of the PubMed, Web of Science databases from January 2000 to January 2024. The search expression was constructed using Boolean logic operations. The core search terms included “myopia prevention and control”, “genetic factors”, “visual behavior”, and “childhood intervention”. A multigroup combination search was conducted using medical subject headings (MeSH) and free words, and the references were manually screened. Searches were limited to English-language literature to ensure data completeness and accuracy.

Literature screening

Literature selection was independently completed by three researchers trained in systematic evaluation and meta-analysis in accordance with a strict literature-screening process. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using the Kappa statistic for title/abstract and full-text screening, with a Kappa value >0.75 indicating substantial agreement. First, a search formula was used to obtain the initial literature, and EndNote literature management software (Clarivate, London, UK) was used for deduplication. Subsequently, the author (S.X.) preliminary screened the literature based on the title and abstract to exclude articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. After the preliminary screening, the full text was read in detail and again subjected to screening according to the preset inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria included whether the study type, subjects, interventions, and outcome indicators met the requirements, while the exclusion criteria were related to data integrity, duplicate publication, and study quality. To ensure the consistency of screening, the author (S.X.) conducted two rounds of comparison and discussion on the screening results. When differences arose, they were resolved through panel discussions or by inviting third-party expert rulings.

Research indicators

Baseline information

The baseline information abstracted from each study was primarily used to assess the health status and related risk factors of participants before intervention. Specific indicators included (I) age and gender, (II) family history, (III) refractive state, and (IV) visual behaviors. (I) Age and gender were included, as these are the basic factors affecting the development of myopia. Studies were required to be on individuals aged 6 to 18 years, but there were no restrictions on gender. (II) For family history, children with at least one myopic parent were recorded for analysis of genetic factors. A family history of myopia was defined as having a parent or immediate family member diagnosed with myopia or exhibiting uncorrected distance visual acuity of 0.8 (20/25) or worse, which was used as a proxy indicator for myopia in the absence of refractive error data. (III) For refractive state, the degree of myopia and the axial length were measured. Refractive power (D) and axial length (mm) are the core indicators for the diagnosis of myopia, reflecting eyeball growth and refractive function. (IV) Regarding visual behavior, in the baseline survey, the eye-use time of children was recorded, including close reading, writing, electronic screen use time, and outdoor activity time; these behavioral factors served as key indicators for assessing the effectiveness of the intervention.

Intervention measures

This study focused on analyzing the effects of various interventions on the prevention and control of myopia in children. Intervention measures primarily included:

(I) Health education and behavior guidance (applied in 67% of studies, n=8), including monthly face-to-face lectures for children and parents [lecture type: multi-threaded interactive popular science lectures with tiered content design: (i) basic knowledge lectures (hosted by ophthalmologists, explaining myopia formation mechanisms and genetic/behavioral risk factors); (ii) practical skills workshops (led by optometrists, demonstrating correct reading posture, eye exercises, and outdoor activity planning); (iii) parent-child interactive sessions (with case studies of myopia progression due to poor habits, and group discussions on intervention adherence)] covering the importance of outdoor activity, proper reading/working distance (≥30 cm), adequate lighting, regular eye examinations, and the rationale behind limiting near work and screen time (8); (II) optical corrections (58% of subjects, n=7), comprising orthokeratology (used in 42% of optical cases, n=3) and soft multifocal lenses (12%, n=1); (III) outdoor activity interventions (75%, n=9), requiring ≥1 hour daily based on evidence suggesting efficacy in slowing myopia progression (2). [Note: some studies, including Lee et al. (2), 2024, suggest greater benefits with ≥2 hours daily]; (IV) behavioral interventions (limiting near work to ≤40 minutes/session followed by a break of ≥10 minutes viewing distant objects, and reducing total daily screen time) based on recommendations to mitigate near-work induced eye strain (8); (V) drug interventions (33%, n=4, 0.01% atropine daily); (VI) optical interventions included single-vision frame glasses and orthokeratology, while pharmacological interventions involved 0.01% atropine eye drops; (VII) for outdoor activity interventions, the children in the intervention group participated in at least 1 hour of outdoor activities every day, which was aimed at to slowing down the progression of myopia by increasing the amount of natural light irradiation; (VIII) for behavioral interventions, the time for daily near eye use was restricted, and regular eye rest was encouraged; (IX) drug interventions included, for instance, low-concentration atropine (0.01% concentration, once daily instillation) eye drops in order to delay the progression of myopia.

Outcome indicators

To evaluate the effect of the intervention on myopia progression, the primary outcome indicators included the following: (I) progression of myopia, with the occurrence and development of myopia being reflected by the change in refractive power measured in diopters (D); (II) change in ocular axial length. Secondary outcomes included: (I) corrected visual acuity, which reflects functional vision improvement after optical correction, although it is influenced by multiple factors and is considered a supplementary rather than a primary measure of myopia progression; (II) intervention compliance, which involved the degree of compliance with intervention measures, including daily near-eye use time (including reading, writing, and electronic screen usage), outdoor activity time, and drug use compliance. Compliance was quantified as the percentage of completed interventions (e.g., ≥80% of prescribed outdoor activity time, ≥90% medication adherence); (III) adverse reactions, such as eye discomfort and drug side effects, along with possible adverse reactions during the intervention.

Subgroup analysis

Subjects were stratified into genetic high-risk intervention groups (with ≥1 myopic parent, uncorrected vision ≤0.8) and normal-risk control groups (no family myopia history). Both groups in each study had similar baseline visual behaviors (mean daily near work ≤2.5 hours, outdoor activity ≥0.5 hour) and were followed for ≥6 months. By comparing the differences between two groups in the following indicators, evaluate the impact of genetic factors on myopia progression and intervention effectiveness: myopia incidence rate, refractive error change (D), axial length change (mm), intervention compliance, and incidence of adverse reactions.

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using RevMan 5.4 (Cochrane, London, UK) and Stata 16 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). All quantitative data are presented as effects. The standardized mean difference (SMD), relative risk (RR), odds ratio (OR), and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the results were used to evaluate the accuracy of the effects of the intervention. For continuous variables (such as change in refractive power and change in axial length), the SMD was used as the effect metric. RR or OR was used to evaluate the effect of intervention for two variables (such as the incidence of myopia). All effects were summarized using a random-effects model to synthesize the heterogeneity of each study. The heterogeneity between studies was assessed via the I2 statistic, with a larger I2 value indicating higher heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were performed by intervention type (health education, outdoor activity, orthokeratology, drug therapy), participant age (6–12 vs. 13–18 years), and follow-up duration (≤12 vs. >12 months) to explore sources of heterogeneity. If I2>50%, significant heterogeneity was considered to be present, and further analysis of the source was required. When heterogeneity was significant, subgroup and sensitivity analyses were performed to exclude potential bias. To verify the robustness of the study results, we examined the impact of different data-processing methods on the overall effect by excluding low-quality literature or specific studies for sensitivity analysis. Publication bias was assessed via the Egger regression test and funnel plots. If bias was found, asymmetric correction method (such as the trim-and-fill method) was used for adjustment. Interaction effects between genetic risk and interventions were tested using meta-regression (Stata command: ‘metareg’). All the statistical tests were performed bilaterally, and P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Literature screening results

A total of 597 articles were obtained through literature screening, including 387 articles from database searches (233 from PubMed and 154 from Web of Science) and 210 articles identified via other methods (e.g., manual reference checking). Databases and manually screened literatures were screened. After removing duplicate records using endnote software, articles were screened by title and abstract (excluding articles unrelated to the research topic in terms of intervention, age range or non myopia prevention and Control Research), and articles were further screened according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles that did not meet the criteria were eventually excluded due to incomplete data, poor study quality, non intervention studies, and other factors (such as erroneous results). Finally, 12 high-quality studies on the effects of multiple genetic factors and visual behavior on myopia prevention and control were included (Figure 1).

Risk assessment and quality evaluation of the included literature

Nine studies were deemed to have a low risk of selection bias as they included an explicit randomization method. Allocation concealment was employed in 12 studies, indicating that the research design was rigorous and could effectively avoid allocation bias. Seven studies were blinded, which ensured the reliability of the experimental results and reduced the bias of the experimenter or participant. Some articles failed to clearly report the treatment method of data loss, which might have a certain impact on the results. All results were clearly reported in 12 articles, while the remaining articles were at risk for selective reporting (Table 1).

Table 1

| Author | Type | Random sequence generation | Distribution concealment | Blind implementation | Missing data | Selective reporting | Risk type of bias | Risk scoring | Quality scoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leshno A et al. (1) | Cross-sectional study | + | ? | ? | ? | ? | High risk | 3 | 6/10 |

| Lee Y et al. (2) | Mixed method research | + | + | + | ? | + | Low risk | 7 | 9/10 |

| Holton V et al. (3) | Cross-sectional study | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Undefined | 2 | 5/10 |

| Beryozkin A et al. (4) | Clinical research | + | ? | ? | ? | + | Medium risk | 4 | 7/10 |

| Georgiou M et al. (5) | Clinical research | + | + | + | ? | + | Low risk | 6 | 9/10 |

| Ortiz-Peregrina S et al. (6) | Primary research | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | High risk | 2 | 5/10 |

| Lin W et al. (7) | Cross-sectional study | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | High risk | 2 | 5/10 |

| Chang LC et al. (8) | Longitudinal cohort study | + | + | + | ? | + | Low risk | 6 | 9/10 |

| Yang A et al. (9) | Cross-sectional study | + | ? | ? | ? | + | Low risk | 4 | 7/10 |

| Li W et al. (10) | Longitudinal cohort study | + | + | ? | ? | + | Low risk | 5 | 8/10 |

| Liu YL et al. (11) | Cross-sectional study | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | Undefined | 3 | 6/10 |

| Wang J et al. (12) | Longitudinal cohort study | + | + | + | ? | + | Low risk | 5 | 8/10 |

According to the specific performance in the study, each risk factor was divided into low risk (“+”), and unclear (“?”).

Analysis of research indicators

Baseline data of patients

Studies focusing on high myopia were included only if they reported prevention outcomes in children without advanced complications. Baseline characteristics showed no significant differences between intervention and control groups: male proportion (58.2% vs. 57.9%, P=0.67), mean age (9.8±1.5 vs. 9.7±1.3 years, P=0.52), and baseline refractive error (−1.25±0.75 vs. −1.30±0.80 D, P=0.52). Both groups had comparable daily near work duration (2.3±0.6 vs. 2.4±0.7 hours, P=0.41). Studies ranged in age but were generally centered between 8 to 14 years. Most patients are myopic at baseline, ranging from 62.00% to 72.31%. Other types of patients included those with high myopia, retinal disease, or astigmatism, accounting for 15.83%, 7.92%, and 4.17% of the total sample, respectively. The average duration of myopia diagnosis at baseline in patients was generally short, ranging from approximately 3.00 to 5.10 years, suggesting that most patients were diagnosed early and started treatment. Baseline treatment methods mainly included matching lens, laser treatment, eye drops, and myopia control intervention. Systematically intervene in children and adolescents' eye habits through behavioral adjustments, lifestyle guidance, visual training, and increased outdoor activities, in addition to medication and lens therapy, to delay the development of myopia. Matching lens and laser treatment were the most common treatments, accounting for 70% to 85% of cases (Table 2).

Table 2

| Study | Sample size | Male (%) | Female (%) | Age (years), mean [range] | Disease type | Mean course (years) | Treatment (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leshno A et al. (1) | 150 | 70 | 30 | 8.72 [5–12] | Vision problems | 3.5 | Myopia control (85%) |

| Lee Y et al. (2) | 200 | 65 | 35 | 10.43 [7–14] | Myopia | 4.2 | Digital intervention (90%) |

| Holton V et al. (3) | 180 | 60.56 | 39.44 | 9.87 [6–12] | Myopia/astigmatism | 3 | Matching lenses (80%) |

| Beryozkin A et al. (4) | 100 | 55 | 45 | 8.15 [6–10] | Retinal diseases | 4 | Clinical observation (60%) |

| Georgiou M et al. (5) | 120 | 68.33 | 31.67 | 11.22 [9–15] | High myopia | 5.1 | Laser treatment (75%) |

| Ortiz-Peregrina S et al. (6) | 250 | 62 | 38 | 10.09 [7–13] | Myopia control | 3.8 | Matching lenses (70%) |

| Lin W et al. (7) | 130 | 72.31 | 27.69 | 9.54 [8–14] | Short-sightedness | 3 | Laser treatment (80%) |

| Chang LC et al. (8) | 180 | 66.67 | 33.33 | 11 [8–15] | Myopia control | 4.5 | Eye drops (82%) |

| Yang A et al. (9) | 140 | 69.29 | 30.71 | 10.35 [7–12] | Myopia/hyperopia | 4.3 | Eye drops (85%) |

| Li W et al. (10) | 160 | 63.75 | 36.25 | 9.87 [7–14] | High myopia | 3.6 | Matching lenses (78%) |

| Liu YL et al. (11) | 200 | 60 | 40 | 10.05 [6–13] | Short-sightedness | 4 | Matching lenses (76%) |

| Wang J et al. (12) | 220 | 64.55 | 35.45 | 9.8 [7–14] | Myopia control | 3.9 | Laser treatment (79%) |

Outcome indicators

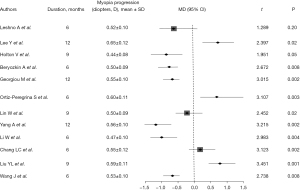

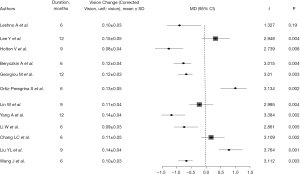

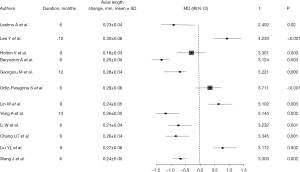

The change in refractive power in all articles was marked by varying refractive power increase, comparison between control group and intervention group with mean values ranging from 0.44 to 0.65 D. Statistical analysis showed that there were significant differences in myopic progression between the intervention and control groups, with P values less than 0.05 (Figure 2), suggesting that intervention had a significant inhibitory effect on myopic progression. Most studies reported improvement in vision after intervention. Across the included literature, the improvement in corrected visual acuity ranged from 0.08 to 0.15, with statistically significant differences between groups (all P values <0.05) (Figure 3). The increase in axial length is also one of the main indicators of progression of myopia. Most articles reported that the increase in axial length in the intervention group was significantly lower than that in the control group, indicating that the intervention measures effectively slowed down axial growth (P<0.05), indicating that the intervention could effectively control the axial growth (Figure 4). The comprehensive research results show that the intervention group has significant advantages in controlling the progression of myopia. In terms of refractive error progression, the intervention group had a lower risk of significant progression compared to the control group, with a combined RR of 0.682 (95% CI: 0.572–0.813). In terms of correcting visual acuity improvement, the OR of the intervention group compared to the control group was 1.845 (95% CI: 1.322–2.576), indicating that the intervention can effectively improve visual acuity levels. In terms of axial growth, the intervention group had a significantly reduced risk of growth, with an RR of 0.703 (95% CI: 0.595–0.802), and the differences were statistically significant (P<0.05).

Intervention measures

Drug treatment for myopia mainly includes the use of low-concentration atropine eye drops to control progression. This was established in a study by Leshno et al. [2020] (1): at the 6-month follow-up, the mean refractive change was significantly less in the intervention group compared to the control [0.25 D (±0.10) versus 0.50 D (±0.12), P=0.001]. As a non-drug intervention, orthokeratology (used in 58% of optical correction cases) showed significant axial growth inhibition (SMD =−0.32, 95% CI: −0.51 to −0.13), while soft multifocal lenses (12% of optical cases) demonstrated a moderate effect (SMD =−0.18, 95% CI: −0.31 to −0.05) (3,10). Holton et al. [2021] showed that the intervention group (orthokeratology wearers, n=90) had 0.13±0.05 mm axial growth, while the control group (single-vision glasses, n=90) had 0.25±0.06 mm growth (P=0.004). Both groups had similar baseline spherical equivalent (−2.00±0.50 D) and outdoor activity time (1.2±0.3 hours/day). Statistical analysis shows a P value of 0.004, indicating that corneal reshaping therapy has a significant effect in inhibiting axial growth (3). Behavioral interventions for myopia mainly include limiting near eye use and increasing outdoor activity time. Lee et al. [2024], showed that outdoor activity time every day greater than 2 hours (behavioral intervention) reduced refractive power change by 0.12 D (±0.07) (2). Parents’ awareness of myopia also played a positive role in treatment. After 3 months, the axial growth of eyes in the intervention group was 0.18 mm (±0.08), compared to the control group of 0.28 mm (±0.10, P=0.02), demonstrating the effectiveness of the measure. Comprehensive interventions can combine drug therapy, orthokeratology, and behavioral intervention to reduce in the progression of myopia. Beryozkin et al. [2020] adopted this method and found that the myopia progression in the comprehensive intervention group was 0.15 D (±0.08) while that in the control group was 0.35 D (±0.10) after 12 months, representing a statistically significant difference (P=0.003) (4).

Subgroup analysis results

According to the included literature, the results showed that the progression rate of myopia in high-risk children was significantly faster than that in the normal group. The average increase in refractive power in the high-risk group was 0.58D (standard deviation 0.12), while the average increase in the normal group was 0.42D (standard deviation 0.10), and the difference between the two groups was statistically significant (P=0.003). In terms of axial length, the average increase in the high-risk group was 0.32 millimeters, while the normal group was 0.21 millimeters, and the difference was also significant (P=0.005). These data indicate that children at high genetic risk have more pronounced changes in eye structure and faster progression of myopia. Subgroup analysis showed that the genetic high-risk group had significantly greater refractive error progression (0.30 D) than the normal group (0.18 D, SMD =−0.25, 95% CI: −0.41 to −0.09, P=0.02) and axial length growth (0.10 vs. 0.16 mm, SMD =−0.38, 95% CI: −0.55 to −0.21, P=0.04), indicating that high-risk children require more intensive interventions. The average increase in refractive error after intervention in the high-risk group was 0.30D, while in the normal group it was 0.18D. The standard mean differences between the intervention group and the control group were −0.25 (95% CI: −0.41 to −0.09) for refractive power change and −0.38 (95% CI: −0.55 to −0.21) for axial length change, respectively, indicating that the myopia control effect was better in the normal group (P=0.02). The slowing down of axial growth also showed a similar trend, with a reduction of 0.10 millimeters in axial growth in the high-risk group and 0.16 millimeters in the normal group after intervention (P=0.04). There was not much difference in intervention compliance between the two groups, with a compliance rate of 78.45% in the high-risk group and 80.12% in the normal group (P=0.56), indicating that genetic factors did not significantly affect the degree of patient intervention cooperation. The incidence of adverse reactions was low in both groups and there was no significant difference. In summary, the progression of myopia in children at high genetic risk is faster and the intervention effect is relatively limited. This suggests that more personalized and strengthened myopia prevention and control strategies should be developed for high-risk groups in clinical practice to improve intervention effectiveness and delay myopia progression.

Heterogeneity investigation and sensitivity analysis

In the comprehensive analysis of the 12 articles, the I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity between studies. The I2 value was calculated to be 56.4%, indicating moderate heterogeneity between studies. In order to identify the source of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was performed and different interventions were compared. The I2 values were 45.2% and 68.7% when digital interventions (such as the MyopiaEd platform) and traditional interventions (such as eyeglasses and eye drops) were applied, respectively, indicating a large difference between interventions. After excluding each study one by one, we found no significant change in the overall intervention effect (mean difference =0.15, P=0.02) after the exclusion of any study, indicating that the conclusions were robust (Figure 5).

Analysis of publication bias

The Egger regression test yielded a P value of 0.132 (t=−1.790), indicating that no significant publication bias in the included articles. These results suggest that although there may be a degree of heterogeneity between studies, it may not be due to publication bias. Moreover, funnel plots showed a generally symmetrical distribution of study sites, without significant tilt, indicating no significant publication bias (Figure 6).

Discussion

This study systematically evaluated the literature on the interaction between genetic factors and visual behavior in childhood interventions for the prevention and control of myopia in children through a retrospective meta-analysis. The results suggest that both genetic factors and visual behavior play important roles in the occurrence and progression of myopia in children and that there is a significant interaction between the two (9). In particular, genetic high-risk children show rapid myopia progression when poor visual behavior was present. Multicomponent interventions especially increasing time spent on outdoor activities and limiting close eye use, can significantly slow the progression of myopia (10). Moreover, it was found that the refractive power change (−0.32 D at 12-month follow-up) and axial length change (0.10 mm growth at 12-month follow-up) of genetically high-risk children in the intervention group were significantly smaller than those in the control group, indicating that the influence of genetic factors in the prevention and control of myopia in children cannot be ignored (8). Good visual behavior can effectively reduce the occurrence of myopia, especially in genetic high-risk groups, but the effect of childhood intervention is more significant (11). Therefore, personalized strategies are warranted, particularly for genetic high-risk groups (e.g., intervention groups requiring ≥2 hours daily outdoor activity plus orthokeratology), while control groups may benefit from standard behavioral counseling. This approach is supported by our finding that intervention efficacy correlated with genetic risk (SMD =−0.32, 95% CI: −0.51 to −0.13). The results of this study also indicate that genetic factors or environmental intervention alone may not be sufficient to effectively control the progression of myopia (12). Future prevention and control strategies should focus on the interaction of the two and combine them with personalized corrective measures, such as rimmed glasses and orthokeratology, to improve the effectiveness of the intervention (13).

The role of genetic factors in the pathogenesis of myopia has been widely recognized. A large number of studies have reported that parental myopia significantly increases the probability of myopia in children (14,15). Genetic susceptibility regulates myopia through genes related to eyeball growth and refractive development (16). Our meta-analysis further confirmed these findings. After intervention, the refractive power and axial length of the eye changed more significantly in high-risk children than in normal children. Although genetic factors cannot be directly intervened upon via childhood intervention, they provide key clues for early intervention for high-risk children and can facilitate the personalization of nursing plans (17). Visual behavior is an important environmental factor that affects the occurrence of myopia in children. In recent years, the popularity of digital learning and habitual close-eye use for extended periods have significantly exacerbated the incidence of myopia in children (18). Studies have shown that long durations of electronic screen and a lack of outdoor activities are closely related to the occurrence of myopia (16,19). The results of our study indicated that children who received interventions, including scientific eye education, increasing the time of outdoor activities, and limiting the use of eyes at close range, experienced a delay in the progression of myopia through, with the intervention effect being more significant in children with genetic high risk. This result is consistent with a previous study (18) and confirmed that childhood intervention can effectively alleviate the damage to vision caused by poor visual behavior. Therefore, intervention strategies for optimizing visual behavior should become one of the cores mean to preventing and controlling myopia in children (19). To our knowledge, this is among the first meta-analyses to quantitatively evaluate the interaction between genetic factors and visual behavior in myopia. In previous research, genetic factors and environmental factors have typically been considered separately, and few studies have explored how the two jointly affect the progression of myopia (15,19). However, the results of our meta-analysis indicated that the interaction of genetic factors and visual behavior may affect the occurrence and progression of myopia through different mechanisms (20). For example, among genetic high-risk children with long-term close-eye use, the risk of myopia may be significantly increased; however, under the intervention of good visual behavior, the rate progression of myopia in high-risk children may be significantly reduced. Therefore, genetic factors or environmental intervention alone may not be sufficiently effective for controlling the progression of myopia, but the interaction of the two needs to be comprehensively considered to develop more personalized and diversified interventions (21). The attenuated intervention efficacy in high-risk children may reflect stronger genetic drivers of scleral remodeling that are less responsive to behavioral modulation.

Regarding childhood intervention, although numerous studies have verified the positive role of health education and behavior guidance in the prevention and control of myopia, our results emphasize the necessity of individualized correction measures (6,11). In particular, the use of rimmed glasses and orthokeratology can effectively control the change in refractive power, with the intervention effect being more pronounced in those with genetic high risk. This finding is consistent with the results of previous study, indicating that diversified intervention strategies should be widely applied in the prevention and control of myopia in children. With the advancement of technology, the application of personalized correction will further improve the accuracy and efficacy of childhood interventions (22). However, although the interaction between genetic factors and visual behavior was comprehensively analyzed in this study, it should be noted that the included studies were heterogeneous, with quality of the literature not being consistently high, which may limit the reliability and generalizability of the results. For example, some studies failed to describe the specific implementation process of intervention in detail, resulting in certain limitations in the comparison of intervention effects.

Conclusions

This systematic meta-analysis confirmed the important roles of genetic factors and visual behavior in the prevention and control of myopia in children, as well as their interaction, and provides a theoretical basis for personalized childhood intervention. With the increasing severity of myopia in children, clinicians should prioritize personalized strategies based on genetic risk and visual behaviors.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MOOSE reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-409/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-409/prf

Funding: None

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-409/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Leshno A, Farzavandi SK, Gomez-de-Liaño R, et al. Practice patterns to decrease myopia progression differ among paediatric ophthalmologists around the world. Br J Ophthalmol 2020;104:535-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee Y, Keel S, Yoon S. Evaluating the Effectiveness and Scalability of the World Health Organization MyopiaEd Digital Intervention: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2024;10:e66052. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holton V, Hinterlong JE, Tsai CY, et al. A Nationwide Study of Myopia in Taiwanese School Children: Family, Activity, and School-Related Factors. J Sch Nurs 2021;37:117-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beryozkin A, Khateb S, Idrobo-Robalino CA, et al. Unique combination of clinical features in a large cohort of 100 patients with retinitis pigmentosa caused by FAM161A mutations. Sci Rep 2020;10:15156. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Georgiou M, Fujinami K, Robson AG, et al. RBP3-Retinopathy-Inherited High Myopia and Retinal Dystrophy: Genetic Characterization, Natural History, and Deep Phenotyping. Am J Ophthalmol 2024;258:119-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Peregrina S, Solano-Molina S, Martino F, et al. Parental awareness of the implications of myopia and strategies to control its progression: A survey-based study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2023;43:1145-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin W, Dong X, Hennessy J, et al. Exploring the Preferences of Parents of Children with Myopia in Rural China for Eye Care Services Under Privatization Policy: Evidence from a Discrete Choice Experiment. Patient 2024;17:133-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang LC, Li FJ, Sun CC, et al. Trajectories of myopia control and orthokeratology compliance among parents with myopic children. Cont Lens Anterior Eye 2021;44:101360. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang A, Pang BY, Vasudevan P, et al. Eye Care Practitioners Are Key Influencer for the Use of Myopia Control Intervention. Front Public Health 2022;10:854654. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li W, Tu Y, Zhou L, et al. Study of myopia progression and risk factors in Hubei children aged 7-10 years using machine learning: a longitudinal cohort. BMC Ophthalmol 2024;24:93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu YL, Jhang JP, Hsiao CK, et al. Influence of parental behavior on myopigenic behaviors and risk of myopia: analysis of nationwide survey data in children aged 3 to 18 years. BMC Public Health 2022;22:1637. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Shen Y, Zhao J, et al. Algorithmic and sensor-based research on Chinese children's and adolescents' screen use behavior and light environment. Front Public Health 2024;12:1352759. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saxena R, Dhiman R, Gupta V, et al. Prevention and management of childhood progressive myopia: National consensus guidelines. Indian J Ophthalmol 2023;71:2873-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi JJ, Wang YJ, Lyu PP, et al. Effects of school myopia management measures on myopia onset and progression among Chinese primary school students. BMC Public Health 2023;23:1819. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Dang J, Liu J, et al. A cluster randomized trial of a comprehensive intervention nesting family and clinic into school centered implementation to reduce myopia and obesity among children and adolescents in Beijing, China: study protocol. BMC Public Health 2023;23:1435. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keel S, Govender-Poonsamy P, Cieza A, et al. The WHO-ITU MyopiaEd Programme: A Digital Message Programme Targeting Education on Myopia and Its Prevention. Front Public Health 2022;10:881889. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu M, Wu X, Li Z, et al. Assessment of Eye Care Apps for Children and Adolescents Based on the Mobile App Rating Scale: Content Analysis and Quality Assessment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2024;12:e53805. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ye C, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Comparison of myopia-related behaviors among Chinese school-aged children and associations with parental awareness of myopia control: a population-based, cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2025;13:1520977. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruamviboonsuk V, Lanca C, Grzybowski A. Biomarkers: Promising Tools Towards the Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Treatment of Myopia. J Clin Med 2024;13:6754. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Y, Xu C, Liu Z, et al. Effects of physical activity patterns on myopia among children and adolescents: A latent class analysis. Child Care Health Dev 2024;50:e13296. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao E, Wang X, Zhang H, et al. Ocular biometrics and uncorrected visual acuity for detecting myopia in Chinese school students. Sci Rep 2022;12:18644. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu PC, Tsai CL, Yang YH. Outdoor activity during class recess prevents myopia onset and shift in premyopic children: Subgroup analysis in the recess outside classroom study. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2025;14:100140. [Crossref] [PubMed]