Does the combination of cartoon stickers and fruit juices reduce premedication anxiety in preschool children?—a randomized controlled trial

Highlight box

Key findings

• The combined intervention (cartoon stickers + fruit juices) reduced preschoolers’ premedication anxiety, outperforming single-modality approaches and demonstrating enhanced efficacy/safety profiles.

What is known and what is new?

• Midazolam (oral/intravenous) achieves 58–72% anxiety reduction but causes sedation-related side effects. Non-pharmacological interventions (e.g., virtual reality, games) show 40–55% efficacy but lack standardization and scalability.

• First evidence that fruit juices’ sweetness (sweet taste receptors on vagus nerve) enhances cartoon stickers’ distraction efficacy, creating a dual-pathway anxiolytic effect (gustatory + visual).

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Demonstrated that dual-sensory interventions (visual + gustatory) reduce premedication anxiety compared to pharmacological monotherapy, challenging the current overreliance on sedatives like midazolam.

• Advocate for inclusion of multisensory interventions in pediatric anesthesia guidelines (e.g., American Society of Anesthesiologists, World Health Organization) as a first-line option for preoperative anxiety management.

Introduction

During the preoperative period, the incidence of clinically significant anxiety has been reported at about 40% to 75% (1,2). Children may manifest dismay behaviors in the holding area such as feeling afraid, trembling, crying, or even combativeness, which may be associated with increased incidence of emergency agitation, nightmares, eating disorders, and maladaptive postoperative behavioral changes (3,4).

Behavioral preparation programs of various kinds, parental presence during induction of anesthesia (PPIA), and sedative premedication have been used to manage preoperative anxiety (5). Midazolam has been commonly administered to young children as premedication (6,7). Due to its bitter taste being difficult to disguise (8), children’s acceptance of midazolam is poor. Oral administration of midazolam is often met with reluctance or refusal, which is called premedication anxiety. In turn, it may aggravate preoperative anxiety.

We performed this study to determine the effect of the combination of cartoon stickers and fruit juices during oral administration on premedication anxiety in children aged 3 to 6 years undergoing elective surgery. We present this article in accordance with the CONSORT reporting checklist (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-73/rc).

Methods

This prospective, randomized, controlled trial was conducted from December 12, 2022, to July 25, 2024. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Children’s Medical Centre (No. SCMCIRB—K2022150-1) and informed consent was taken from all the patients’ parents or guardians.

Participants

Patients between 3 and 6 years of age, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status (ASA-PS) 1 to 3, were eligible for our study. They were scheduled for elective ambulatory hernia repair, urogenital procedures, and adenoidectomy under general anesthesia. Children with emergency surgery, a history of previous anesthesia, allergies to midazolam, stickers, and fruit juices, or the refusal of parents or legal guardians were excluded from participation.

Randomization and preoperative management

Based on the computer-generated randomization list, participants were randomly allocated to either the control group (Group A) or the intervention groups (Group B, Group C and Group D) in a 1:1:1:1 ratio.

Children enrolled in Group A received 0.5 mg/kg midazolam mixed with 85% monosaccharide syrup (registered number of approval: H33020125). Participants in Group B received some animated cartoon stickers 5 min before premedication (monosaccharide syrup mixtures), such as Peppa Pig, Super Flyer, Balala the Fairies, Ultraman, etc., and they could choose one of the stickers according to their preference. In Group C, three kinds of fruit juices (apple juice, peach juice, and orange juice) were offered to children to choose from and a midazolam fruit juices mixture would be given as premedication. In Group D, participants were given their favorite cartoon stickers and fruit juices mixed with midazolam before premedication. Midazolam was mixed with equal volumes of syrup or fruit juice in a transparent carton noggin for a final concentration of 2.5 mg/mL. The mixtures were prepared just before administration by an anesthesiologist, independent of the trial. And during mixing, keep the children out of sight.

Patients were assigned in blocks of four with a sealed envelope, which could only be opened by a designated nurse who was not involved in other segments of this study and left without informing another nurse of the groups. One researcher implemented the interventions for children and another recorded the modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale-Short Form (mYPAS-SF) scores.

The primary outcome of this study was the anxiety exhibited by children during premedication administration in our preoperative holding area.

All operations were conducted in the morning and children were taken to the preoperative holding area with a nurse around 30 min before surgery. Participants’ anxiety levels were assessed using the mYPAS-SF (9). The mYPAS-SF is the simplified kind of the mYPAS, whose score ranges from 22.9 to 100, higher scores relate to more significant anxiety and consist of 18 items distributed over four categories (activity, vocalization, emotional expressivity, and arousal). A mYPAS-SF score of more than 30 defined significant anxiety (10). For each measurement, a blinded researcher who was not responsible for the premedication administration recorded the scores three times during the observation period and was absent for the rest of the research process.

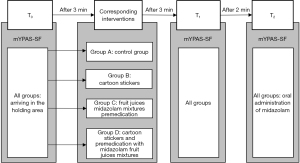

In our study, the mYPAS-SF scores were evaluated at three time points (Figure 1). The moment when baseline anxiety levels were measured in all groups (T0). After 3 min of waiting in the holding area, subjects in Group B, Group C and Group D received the corresponding interventions respectively, after 3 min of the interventions (T1), participants’ anxiety levels were assessed using mYPAS-SF, and 2 min after T1, mYPAS-SF scores were measured again upon administrating 0.5 mg/kg midazolam (T2). In group A, children waited for 6 minutes in the preoperative holding area, after this 6 min, a researcher evaluated children’s levels of anxiety using the mYPAS-SF (T1), and mYPAS-SF was re-recorded during administrating 0.5 mg/kg midazolam 2 min after T1.

Statistical analysis

In a pilot study of 30 participants, the mean [standard deviation (SD)] mYPAS-SF scores at the time of having midazolam were 41.0 (13.6), 32.5 (4.7), 27.8 (4.5) and 24.4 (2.4), in Groups A, B, C and D respectively. The previous study reported that a reduction of 15 points in the anxiety score would be remarkable (6), which indicates that the expected SD is 15. The sample size of 28 per group was determined by an α value of 0.05 and a test power of 90%, which was conducted using the PASS software (Power Analysis and Sample Size software, version 15.0.5). The sample size was enlarged to 148 to allow for potential post-recruitment drop-out.

Outcome data were analyzed in the intention to treat (ITT) population. Statistical analysis was performed using R 4.22. The assumption of normal distribution was proven by the Shapiro-Wilk tests. Normally distributed data were reported as mean (SD). Non-normally distributed and ordinal data were reported as median (inter-quartile range). It was expressed as median (inter-quartile range) and analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test, if data were not normally distributed. When there was a significant intergroup difference, we performed a post hoc Mann-Whitney U test with Bonferroni correction, for multiple tests (six comparisons). A Bonferroni-adjusted P value <0.008 (0.05/6) was considered statistically significant. We also applied the repeated measures one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare the change in mYPAS-SF scores over time among the four groups. Categorical variables were analyzed using the X2 test or the Fisher’s exact test.

A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Adjusting the Bonferroni was to control type I errors for multiple tests.

Results

A total of 155 children, with 37 in each group were initially enrolled in the study, and the flow diagram of participants is presented in Figure 2. The surgery of two patients in Group B and one in Group C and Group D was suspended respectively. Three children in Group A refused the operation in the preoperative holding area. Consequently, the study was implemented with 148 patients. Four groups were homogeneous in terms of age, gender, weight, ASA-PS, and surgical characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Group A (n=37) | Group B (n=37) | Group C (n=37) | Group D (n=37) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.1 (0.9) | 4.4 (0.9) | 4.5 (0.9) |

| Gender (M/F) | 24/13 | 23/14 | 23/14 | 24/13 |

| Weight (kg) | 18.8 (5.6) | 18.2 (4.3) | 17.9 (3.7) | 18.5 (3.4) |

| ASA PS (1/2/3) | 21/8/8 | 25/5/7 | 27/5/5 | 26/4/7 |

| Onset of sedation (min) | 18.4 (1.0) | 19.0 (1.4) | 19.2 (1.7) | 18.8 (1.2) |

| Type of surgery, n (%) | ||||

| Hernia repair | 11 (29.7) | 10 (27.0) | 12 (32.4 | 15 (40.5) |

| Urogenital procedures | 16 (43.2) | 14 (37.8) | 11 (29.7) | 11 (29.7) |

| Adenoidectomy | 10 (27.0) | 13 (35.1) | 14 (37.8) | 11 (29.7) |

Unless otherwise stated, values are mean (SD), or actual numbers. Group A, control group (premedication with traditional midazolam monosaccharide syrup mixtures); Group B, cartoon stickers before traditional premedication; Group C, fruit juices midazolam mixtures premedication; Group D, cartoon stickers and premedication with midazolam fruit juices mixtures. ASA PS, American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status; F, female; M, male; SD, standard deviation.

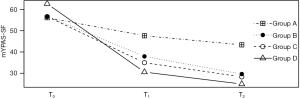

At T0, there was no significant difference in the baseline mYPAS-SF scores among the groups (P=0.17). Children in Group B manifested lower mYPAS-SF scores than those in Group A at T1 (P=0.043) and T2 (P=0.01). Patients in Group C showed lower mYPAS-SF scores than those in Group A at T1 (P<0.001) and T2 (P<0.001). There was no statistically significant difference in the mYPAS-SF scores of children in Group B and Group C at time T1 (P=0.13) and T2 (P=0.15).

In the four groups, mYPAS-SF scores measured at T0 were significantly higher than T1 and T2, which was remarkably shown in Group D (Table 2).

Table 2

| Time | Group A (n=37) | Group B (n=37) | Group C (n=37) | Group D (n=37) | P value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | 51.2 (22.9–100) | 53.4 (39.6–75.0) | 52.1 (41.6–67.7) | 62.5 (50.0–76.0) | 0.17 |

| T1 | 53.4 (22.9–100)*,#,Δ | 41.6 (35.4–66.7)*,# | 35.4 (31.3–39.6)* | 31.1(22.9–33.3) | <0.001 |

| T2 | 49.8 (22.9–100)*,#,Δ | 33.3 (31.3–52.1)*,# | 29.2 (27.1–33.3)* | 24.3 (22.9–33.3) | <0.001 |

Values are median (inter-quartile range) for continuous variables. Group A, control group (premedication with traditional midazolam monosaccharide syrup mixtures); Group B, cartoon stickers before traditional premedication; Group C, fruit juices midazolam mixtures premedication; Group D, cartoon stickers and premedication with midazolam fruit juices mixtures. †, Kruskal-Wallis test. *, Bonferroni-adjusted P<0.017 vs. Group D after Mann-Whitney U test. #, Bonferroni-adjusted P<0.017 vs. Group C after Mann-Whitney U test. Δ, Bonferroni-adjusted P<0.017 vs. Group B after Mann-Whitney U test. T0, immediately after entering the preoperative holding area (baseline); T1, after 3 min of interventions; T2, the time of midazolam oral administration. mYPAS-SF, modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale-Short Form.

In all groups, there was a time-dependent decrease in anxiety levels from baseline to the moment just before having midazolam. However, the mYPAS-SF scores in Group D showed a sharp downward trend, compared with other groups (Figure 3).

Discussion

In this prospective, randomized, and controlled study, we found that an extensive measure combined of favorite carton stickers and fruit juices before midazolam oral administration significantly reduced premedication anxiety.

Preoperative anxiety is recognized to modulate pharmacological responses by altering gastric motility and patient compliance, potentially affecting midazolam absorption and onset (11). For instance, heightened anxiety may delay gastric emptying, reducing bioavailability by 15–20% in children—a phenomenon observed in trials comparing oral and intravenous midazolam (12). Anxiety-driven refusal or incomplete medication intake can delay induction, as seen in study where 18–25% of anxious children required dose adjustments or alternative methods (2). Our dual-sensory intervention (Group D) addressed this by reducing pre-dose anxiety, thereby improving medication acceptance and procedural efficiency.

Midazolam is routinely used in our hospital as a premedication. It would decrease the incidence of preoperative anxiety and ease the anesthetic induction (13). However, several studies have demonstrated that the administration of midazolam is a source of substantial anxiety in children and we also found they took the premedication reluctantly (3,14). However, midazolam’s clinical utility is tempered by risks of anterograde amnesia (explicit memory impairment with intact implicit memory) and postoperative behavioral disturbances, as reported in pediatric cohorts (15,16). These effects likely stem from GABAA receptor modulation, with dose-dependent plasma concentrations exceeding 30 ng/mL correlating to prolonged emotional dysregulation (16).

Kain et al. reported that the mYPAS score of children varied from 23 to 59 in the preoperative holding area with a median of 23 and a mean (SD) of 28 [8] (17). In the current study, the median mYPAS-SF scores ranged from 45.8 to 56.3 when the child arrived in the preoperative holding area, which was higher than those of one of our previous study (mYPAS-SF scores was 39.6) (10), and those of Kain and his colleagues’ study. We used mYPAS-SF to assess the children’s anxiety as a valid scale. It has been verified that children with a higher baseline level of anxiety gain more benefits from the administration of midazolam (18).

A Portugal study found that preschool children who received a sticker as a reward could promote vegetable consumption (19). Another study reported that pediatric dentists used a sticker as one of the rewards to encourage their young patients (20). Children aged 3–6 years are usually glad to receive a sticker from their teachers as a reward in kindergarten in daily life. In our study, children were asked to choose one of the animated cartoon stickers such as Peppa Pig, Super Flyer, Balala the Fairies and Ultraman, etc. Children had been familiar with these characters through cartoon movies.

After 3 minutes having arrived at the holding area, children were given various stickers to choose from, and quite a few children accepted what they chose gladly at the very start. Interestingly, at the time of oral midazolam administration, some of them cried loudly or refused vehemently, which was the same as the findings of the study about the implementation of nutrition education strategies to promote vegetable consumption in preschool children (14). In that study, the use of stickers was shown advantageous in the short term, but it was not effective subsequently. And some assumed that stickers are useful in the first phase but are not enough to sustain long-term benefits.

Some studies demonstrated that disguising the odor of inhalation with fruit flavors could improve the mask acceptance of children (21,22). What is more, fruit flavor probably could put anxious children at ease (22). Therefore, in our study, we used a midazolam fruit juice mixture for better premedication acceptance. Traditionally, we mixed midazolam with a thick 85% monosaccharide syrups. The thick viscous mixture may adhere to the oral mucosa and prolong the retention time, thus increasing the sensation of bitterness. On the contrary, fruit juice mixture is thinner than syrup and only with brief contact with the oral mucosa, which leads to a reduction of the bitter taste. All above could explain our low rate of premedication anxiety in Group C. Though the previous study had found that the onset time of oral midazolam mixed with fruit juice was longer than that of syrup mixture (23), the comparison of the onset time between the two kinds of the mixture in our study has shown no significant difference. Children in Group B (cartoon stickers) and Group C (fruit juice) exhibited relatively lower premedication anxiety levels than children in Group A at T1 and T2. Subjects in Group D (cartoon stickers and fruit juice) had the significantly lowest mYPAS-SF scores at the time of midazolam administration among the four groups.

Bumin et al. showed that playing with dough alleviates premedication anxiety effectively (14). We didn’t adopt the previous means which were easy to be swallowed by kids mistakenly. Giving toys has been verified as a useful way to ease premedication anxiety (13), however, it has been not recommended for use because of cleanliness anxieties. Other interventions such as using clowns and showing cartoons may need healthy volunteers, specific costumes, and additional equipment.

Previous evidence shows that a hypnosis intervention before surgery is more effective in reducing preoperative anxiety and post-operative behavioral disorders than midazolam, a common benzodiazepine medication to reduce anxiety before surgeries (24). A recent study showed that children who received a narcosis comic or a narcosis comic and an audio hypnosis intervention before surgery showed low preoperative anxiety and high post-operative comfort (25). Such approaches align with our multimodal strategy, though further comparative studies are warranted to optimize integration into clinical workflows.

Although our study manifested the beneficial effects of giving some interventions to reduce premedication anxiety in children, a few limitations remain in the study. Blinding was impossible because cartoon stickers and fruit juices were visible to all investigators and participants, therefore, we tried to minimize the bias of the researchers who recorded the mYPAS-SF scores by not interpreting the main purpose of the trial or why some participants had an intervention and others did not. Another limitation is that the type of surgery might vary among the four groups, however, study has shown that there is no significant association between the mYPAS score of children and the type of surgery before premedication administration (15). Besides, reliance on the mYPAS-SF for anxiety assessment, while valid, may overlook physiological stress responses (e.g., cortisol) that influence medication efficacy.

Conclusions

In summary, our findings suggest that the synergistic use of cartoon stickers (providing visual distraction and emotional comfort) and fruit juices (offering palatable sensory engagement) effectively reduces premedication anxiety in pediatric surgical patients. This aligns with emerging evidence that multimodal non-pharmacological interventions, such as augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR), demonstrate superior anxiety reduction compared to single-modality approaches.

Acknowledgments

We thank Department of Anesthesiology, Shanghai Children’s Medical Centre Affiliated to School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University for donating cartoon stickers and fruit juices to pediatric patients.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CONSORT reporting checklist. Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-73/rc

Trial Protocol: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-73/tp

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-73/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-73/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tp.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tp-2025-73/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai Children’s Medical Centre (No. SCMCIRB—K2022150-1) and informed consent was taken from all the patients’ parents or guardians.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Liu W, Xu R, Jia J, et al. Research Progress on Risk Factors of Preoperative Anxiety in Children: A Scoping Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:9828. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wollin SR, Plummer JL, Owen H, et al. Predictors of preoperative anxiety in children. Anaesth Intensive Care 2003;31:69-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golden L, Pagala M, Sukhavasi S, et al. Giving toys to children reduces their anxiety about receiving premedication for surgery. Anesth Analg 2006;102:1070-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qiao H, Chen J, Lv P, et al. Efficacy of premedication with intravenous midazolam on preoperative anxiety and mask compliance in pediatric patients: a randomized controlled trial. Transl Pediatr 2022;11:1751-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang R, Huang X, Wang Y, et al. Non-pharmacologic Approaches in Preoperative Anxiety, a Comprehensive Review. Front Public Health 2022;10:854673. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Lee J, Lim H, et al. Cartoon distraction alleviates anxiety in children during induction of anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2012;115:1168-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manyande A, Cyna AM, Yip P, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for assisting the induction of anaesthesia in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD006447. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isik B, Baygin O, Bodur H. Effect of drinks that are added as flavoring in oral midazolam premedication on sedation success. Paediatr Anaesth 2008;18:494-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jenkins BN, Fortier MA, Kaplan SH, et al. Development of a short version of the modified Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale. Anesth Analg 2014;119:643-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu PP, Sun Y, Wu C, et al. The effectiveness of transport in a toy car for reducing preoperative anxiety in preschool children: a randomised controlled prospective trial. Br J Anaesth 2018;121:438-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyslop MC, Papaioannou DE, Bolt R, et al. Barriers and enablers to recruiting participants within paediatric perioperative and anaesthetic settings: lessons learned from a trial of melatonin versus midazolam in the premedication of anxious children (the MAGIC trial). BJA Open 2025;13:100375. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tyagi P, Tyagi S, Jain A. Sedative effects of oral midazolam, intravenous midazolam and oral diazepam in the dental treatment of children. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2013;37:301-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cox RG, Nemish U, Ewen A, et al. Evidence-based clinical update: does premedication with oral midazolam lead to improved behavioural outcomes in children? Can J Anaesth 2006;53:1213-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bumin Aydın G, Yüksel S, Ergil J, et al. The effect of play distraction on anxiety before premedication administration: a randomized trial. J Clin Anesth 2017;36:27-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kain ZN, Hofstadter MB, Mayes LC, et al. Midazolam: effects on amnesia and anxiety in children. Anesthesiology 2000;93:676-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGraw T, Kendrick A. Oral midazolam premedication and postoperative behaviour in children. Paediatr Anaesth 1998;8:117-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kain ZN, Mayes LC, Cicchetti DV, et al. The Yale Preoperative Anxiety Scale: how does it compare with a “gold standard”? Anesth Analg 1997;85:783-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finley GA, Stewart SH, Buffett-Jerrott S, et al. High levels of impulsivity may contraindicate midazolam premedication in children. Can J Anaesth 2006;53:73-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braga-Pontes C, Simões-Dias S, Lages M, et al. Nutrition education strategies to promote vegetable consumption in preschool children: the Veggies4myHeart project. Public Health Nutr 2022;25:1061-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coxon J, Hosey MT, Newton JT. What reward does a child prefer for behaving well at the dentist? BDJ Open 2017;3:17018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewis RP, Jones MJ, Eastley RJ, et al. ‘Fruit-flavoured’ mask for isoflurane induction in children. Anaesthesia 1988;43:1052-4.

- Gupta A, Mathew PJ, Bhardwaj N. Flavored Anesthetic Masks for Inhalational Induction in Children. Indian J Pediatr 2017;84:739-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khalil SN, Vije HN, Kee SS, et al. A paediatric trial comparing midazolam/Syrpalta mixture with premixed midazolam syrup (Roche). Paediatr Anaesth 2003;13:205-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Calipel S, Lucas-Polomeni MM, Wodey E, et al. Premedication in children: hypnosis versus midazolam. Paediatr Anaesth 2005;15:275-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt B, Thomas C, Göttermann A, et al. Reducing Perioperative Anxiety and Postoperative Discomfort in Children With Hypnosis Before Tonsillotomy and Adenoidectomy: A Prospective Randomized Trial. Health Sci Rep 2025;8:e70484. [Crossref] [PubMed]