Disorder of written expression and dysgraphia: definition, diagnosis, and management

Introduction: definitions and disagreement

At its broadest definition, dysgraphia is a disorder of writing ability at any stage, including problems with letter formation/legibility, letter spacing, spelling, fine motor coordination, rate of writing, grammar, and composition. Acquired dysgraphia occurs when existing brain pathways are disrupted by an event (e.g., brain injury, neurologic disease, or degenerative conditions), resulting in the loss of previously acquired skills. In contrast, this review will concentrate on developmental dysgraphia, i.e., the difficulty in acquiring writing skills despite sufficient learning opportunity and cognitive potential. This article will use the terms dysgraphia and specific learning disorder with impairment of written expression in their broadest terms, to encompass any difficulty an individual may have in written communication.

Much controversy exists regarding the precise definition of and deficits seen in dysgraphia, depending on the theoretical mechanisms attributed to the disorder (1). Historically, dysgraphia was most often defined as an impairment in the production of written text, usually due to a lack of muscle coordination. Specific testing in affected children highlighted minor differences in performance of fine motor tasks (e.g., repeated finger tapping) or abnormal measures of hand strength and endurance (2). These deficits stemmed from hindrance in fine motor coordination, visual perception, and proprioception and manifested an illegible or slowly formed written product. Oral spelling was usually preserved. This conceptualization of dysgraphia has been categorized as “motor” or “peripheral” dysgraphia (3).

Secondly, Deuel (4) proposed a second subtype of dysgraphia termed “spatial dysgraphia”. The primary impairment in this sub-type of dysgraphia was thought to be related to problems of spatial perception, which impaired spacing of letters and greatly impacted drawing ability. In such cases, oral spelling and finger tapping were preserved but drawing, spontaneous writing, and copying text were impaired.

However, others have placed much more focus on the language processing deficits related to written expression, with less emphasis on any motor issues. Qualifying terms for this type of dysgraphia include “dysorthography”, “linguistic dysgraphia”, or “dyslexic dysgraphia” (5). The primary mechanism of this dysgraphia is related to inefficiency of the “graphomotor loop”, in which the phonologic memory (regarding sounds associated to phonemes) communicates with the orthographic memory (regarding written letters). Impaired verbal executive functioning, including storage and working memory, have also been related to this disorder (5). Oral spelling, drawing, copying, and finger tapping are usually preserved in this type of dysgraphia. In contrast but related to dysgraphia, dyslexia is theorized to result from two-way dysfunction of the “phonologic loop”, which is the communication between orthographic and phonologic processes.

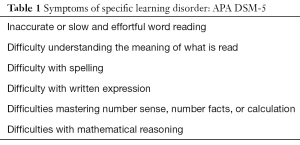

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) (6) includes dysgraphia under the specific learning disorder category, but does not define it as a separate disorder. According to the criteria, a set of symptoms (Table 1) should be persistent for a period of at least 6 months in the context of appropriate interventions in place. For any specific learning disorder, the academic skills as measured by individually administered standardized tests must fall significantly below expectations for the child’s age. The onset of difficulty in learning is generally during early school years; however, it is more apparent as the complexity of work increases with progression to higher grades. Other causes of learning difficulty include intellectual disability, vision impairment, hearing impairment, underlying mental or neurological disorder, and lack of adequate learning support or academic instructions.

Full table

In the United States, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) revised in 2004 broadly defines “Specific Learning Disability” in the following manner (7):

- The child does not achieve adequately for the child’s age or to meet State-approved grade-level standards in one or more of the following areas, when provided with learning experiences and instruction appropriate for the child’s age or State-approved grade–level standards: Oral expression, listening comprehension, written expression, basic reading skills, reading fluency skills, reading comprehension, mathematics calculation, or mathematics problem solving.

- The child does not make sufficient progress to meet age or State-approved grade-level standards in one or more of the areas when using a process based on the child’s response to scientific, research-based intervention; or the child exhibits a pattern of strengths and weaknesses in performance, achievement, or both, relative to age, State-approved grade-level standards, or intellectual development, that is determined by the group to be relevant to the identification of a specific learning disability, using appropriate assessments; and the group determines that its findings are not primarily the result of a visual, hearing, or motor disability; mental retardation; emotional disturbance; cultural factors; environmental or economic disadvantage; or limited English proficiency.

Between 10% and 30% of children experience difficulty in writing, although the exact prevalence depends on the definition of dysgraphia (8). As with many neurodevelopmental conditions, dysgraphia is more common in boys than in girls (9). Handwriting problems are a frequent reason for occupational therapy consultation. Dysgraphia and disorders of written expression can have lifelong impacts, as adults with difficulty writing may continue to experience impairment in vocational progress and activities of daily living (10).

Writing development

As noted above, the concept of “writing” encompasses a broad spectrum of tasks, ranging from the transcription of a single letter to the intricate process of conceptualizing, drafting, revising, and editing a doctoral dissertation. Writing is an important academic skill that has been associated with overall academic achievement (11). On average, writing tasks occupy up to half of the school day (12), and students with difficulty writing are often mislabeled as sloppy or lazy rather than being recognized as having a learning disorder. Deficient handwriting has been associated with lower self-perception, lower self-esteem, and poorer social functioning (13,14).

The acquisition of writing follows a step-wise progression in early childhood; individuals who struggle with foundational writing skills are likely to exhibit greater delays as they fail to match their peers’ growth in writing ability. In preschool, children are taught to copy symbols and shapes to develop the basic visual-motor coordination skills for transcription. Letter awareness typically begins in kindergarten and progresses through second grade, during which time the child becomes familiarized with the relationship between sounds and phonemes while continuing to grow in motor skills (15). Automaticity, in which individual letter writing has become a rote response, is usually developed by third grade (16). As many American school curricula no longer include specific instruction on the steps of letter formation, children who struggle to develop automaticity may fail to acquire this skill (5,17). Automaticity and handwriting should continue to improve through the elementary school years (18) with implications for long-term outcomes; notably, the skill of automaticity is associated with higher quality and longer length of writing products in high school and college (19,20).

Beyond the early school years, writing projects require the additional ability to organize, plan, and implement a complete written product. Such tasks require the recruitment of executive functioning and higher-order language processing. For example, writing a sentence requires several steps: (I) internally creating the desired statement; (II) segmenting the desired statements into sections for transcription; (III) retaining the sections in verbal working memory while executing the task of writing; and (IV) checking that the completed written product matches the original thought. Writing more complex products such as paragraphs or essays requires additional planning, organization, and revision to stitch together multiple statements and thoughts into a coherent whole. Failure to develop writing automaticity by third grade greatly increases the likelihood of difficulty in more complex writing tasks, as the child’s higher cognitive functions may be preoccupied by the graphomotor requirements of letter formation.

Mechanisms and etiology

Many of the theories regarding mechanisms of dysgraphia have been derived from studies of individuals with acquired dysgraphia (21,22). Writing has been shown to be a complex process that requires the higher order cognition (language, verbal working memory and organization) coordinated with motor planning and execution to constitute the functional writing system (23). Different writing tasks require different cognitive processes, and individuals with dysgraphia may have disorders in one or more areas. For example, when asked to spell a dictated word, the listener must utilize phonological awareness to access phonological long-term memory and the associated lexical-semantic representations. This in turn activates the orthographic long-term memory to create abstract letter representations that require motor planning and coordination to execute the task of writing, all maintained in the working memory. Spelling a pseudoword or novel word requires the function of sublexical spelling process that applies known phoneme-graphene conventions to predict the correct spelling. Generating a new word spontaneously would first require the usage of orthographic skills, which would then access the lexical representation. Writing rapidly and fluidly requires motor planning and coordination mediated by the cerebellum. Throughout the writing task, visual and auditory processing and attention is crucial to the production of legible writing.

Impairment in even one facet of the writing process can impair an individual’s ability to generate an age-appropriate product (24). Although researchers have theorized that different subtypes of dysgraphia may be correlated to different mechanisms (25), newer studies have demonstrated interrelations between brain areas responsible for automaticity, language, and motor coordination. The perceived divergence between theories of dysgraphia may not be as great as once thought. For example, children with dyslexia have also been noted to be at increased risk for other mild motor deficits in tasks like finger tapping, riding a bike, and tying shoelaces.

Increased attention has also been placed on the cerebellum as playing a role in dysgraphia. Case studies have shown that cerebellar injury can cause symptoms of acquired dysgraphia, indicating that it plays some role in the coordination of writing (21). Functional imaging studies have also demonstrated that this region of the brain plays a vital role in language and automaticity (26). Possible mechanisms of involvement include the hypothesis that the cerebellum is required in the development of a neural system or framework, which can be disrupted in different ways and result in different functional impairments (1).

Genes and their role in the possible etiology or mechanisms of learning disorders is an emerging field. Genetic aggregation studies suggest that verbal executive function tasks, orthographic skills, and spelling ability may have a genetic basis. For example, genes on chromosome 15 have been linked to poor reading and spelling (27) and genes on chromosome 6 have been linked to phonemic awareness (28). Individuals with learning disabilities and their family members have been noted to have differential brain activation patterns on functional magnetic resonance imaging, suggesting a genetic contribution, but not causation (29). As the field of genetics continues to evolve, more information regarding the genetics of learning disorders like dysgraphia is likely to emerge.

Co-morbidities

Dysgraphia may occur in isolation but is also commonly associated with dyslexia as well as other disorders of learning. Depending on the definitions utilized, anywhere from 30% to 47% of children with writing problems also have reading problems. In addition, difficulty in writing can be seen in many other neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, cerebral palsy, and autism spectrum disorder. Research demonstrates that 90–98% of children with these disorders struggle with writing (29-32). Developmental coordination disorder (DCD), in which individuals have deficiencies in motor development and motor skill acquisition, often also affects writing development; around half of those with DCD also exhibit impaired writing abilities (33). With regards to the association between learning disorders and mental health disorders, co-morbidity is the rule, not the exception (34,35). Given this high risk of co-morbidity, clinicians should be surveilling patients for possible related conditions; e.g., the patient with autism spectrum disorder should be monitored for problems with reading, writing, and math while the patient with dysgraphia may warrant an investigation of co-morbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Red flags

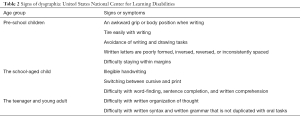

As academic demands increase and neurodevelopment progresses, dysgraphia may manifest in a variety of signs and symptoms. It can affect one or more levels of the writing process. As noted above, handwriting is typically developing in the early school years, and thus, dysgraphia is usually not recognized during this period. However, dysgraphia (especially isolated dysgraphia) may not be recognized, even into the young adult years. Co-morbid dyslexia and dysgraphia is more readily recognized, although impairments in reading ability are usually prioritized and addressed over impairments in writing. The National Center for Learning Disabilities has published a summary of warning signs for dysgraphia based on the age and stage of development (Table 2) (36). As in seen in the table, dysgraphia symptoms manifest first as concrete impairments at younger ages and later as abstract impairments at older ages.

Full table

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of specific learning disability is typically made in an educational setting by a team assessment, which often includes occupational therapists, speech therapists, physical therapists, special education teachers, and educational psychologists. In the United States, most often, the diagnosis is made following an assessment towards eligibility for an individualized educational plan (36). The diagnosis of a learning disability or dysgraphia can also be given through a psychoeducational evaluation outside of the educational system. As the term “dysgraphia” is not recognized by the American Psychological Association, there is no professional consensus on specific diagnostic criteria. As in the case for other learning disorders, a key factor should be the degree of difficulty that the writing impairment imposes on the child’s access to the general education curriculum. Evidence should be drawn from multiple sources and contexts, including observation, anecdotal report, review of completed work, and normative data.

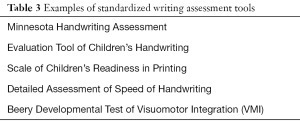

One expert recommendation for the diagnosis of dysgraphia is the following: slow writing speed; illegible handwriting; inconsistency between spelling ability and verbal intelligence quotient; and processing delays in graphomotor planning, orthographic awareness, and/or rapid automatic naming. Secondary tests to consider are evaluations of pencil grip and writing posture. Formalized handwriting assessments (Table 3) can be used to measure the speed and legibility of students when copying letters, words, sentences, and/or pseudowords. Visual-motor integration assessment may include evaluations such as the Beery Developmental Test of Visuomotor Integration (VMI) (37); however, these tests typically do not analyze difficulties specific to orthographic processes. Children with suspected dysgraphia should be evaluated for other potential learning problems given the high rates of co-morbidity with dyslexia and other learning disorders.

Full table

There is no medical testing required or available for diagnosing dysgraphia. However, given the high rate of co-morbidity between psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, and learning disorders, the physician should investigate for symptoms of possible related conditions. The physician should conduct a thorough neurologic examination, including “soft” neurologic signs like poor coordination, dysrhythmias, mirror movements, and overflow movements. Co-morbid neurodevelopmental disorders (e.g., autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) and mood disorders (e.g., anxiety, depression) can be evaluated through the use of semi-structured interviews and/or validated parent and teacher report forms. Should screening procedures indicate any areas of concerns, the general medical practitioner should consider referring for specialist consultation for additional diagnostic conceptualization and treatment recommendations, including child neurology, child psychiatry, developmental-behavioral pediatrics, or other mental health providers.

Management

The primary intervention for dysgraphia and other learning disorders occurs in the educational setting. Interventions can generally be stratified into the following levels: (I) accommodation, where the student accesses the mainstream education curriculum with supportive or assistive resources without changing the educational content; (II) modification, where the school adapts the student’s goals and objectives as well as provides services to reduce the effect of the disability; and (III) remediation, where the school provides specific intervention to decrease the severity of the student’s disability. As the manifestations of dysgraphia and other learning disorders change with shifting academic demands and cognitive development, management of these conditions is a fluid and life-course process that must adapt with the most current level of impairment. As outlined by IDEA, the school system should assess and provide the necessary supports for the student’s needs in the educational setting.

Accommodations

Accommodations should be directed to decrease to the stress associated with writing. Specific devices may be utilized, such as larger pencils with special grips and paper with raised lines to provide tactile feedback. Extra time can be permitted for homework, class assignments, and quizzes/tests. Depending on the student’s comfort level, alternative ways of demonstrating knowledge (e.g., oral or recorded responses rather than written examination) can be considered. Technologic accommodations include automated spellcheck, voice-to-text recognition software, tablets, and computer keyboards; as devices become increasingly more advanced, new devices should be considered for their application in the classroom. However, handwriting practice should continue at school as written language is still needed for many daily tasks (e.g., filling out forms). Research has also demonstrated that the process of writing words by hand may provide a unique impetus to learning (38). It is important to note that accommodations may not directly address impairment of executive functioning tasks related to writing, including planning and organization. Computers and voice-to-text supports can decrease writing stress in those with continued automaticity challenges, but these accommodations do not address higher-level writing difficulties (39).

Modifications

Dysgraphia may require modifications to the student’s academic program, especially with regards to written products. Teachers can opt to scale down large written assignments, break up large projects into smaller ones, or grade students based on a single dimension of their work (e.g., content or spelling, not both). In general, following the “least restrictive environment” for learning, the school should strive to keep the student within the mainstream education environment as much as possible.

Remediation

Remediation should be determined by the individual student’s severity of difficulty in written expression. As with many neurodevelopmental conditions, early intervention produces the greatest gain (24). A stratified approach may be utilized following a response-to-intervention model (RTI). This model consists of three tiers of intervention; students who continue to struggle to lower tiers “step up” to higher tiers. Tier 1 consists of preventative screening on all students for learning differences. Expert recommendations have been written for general education teachers regarding ways to encourage sound writing habits (9). Tier 2 consists of targeted intervention towards students with specific learning issues. Tier 3 focuses the most intensive treatment on students who have continued to struggle and require the most support. In most intervention studies, students usually demonstrate improvement after 20 lessons over several weeks.

Most often, intervention for dysgraphia in the early elementary years focuses on developing fine motor skills. Motor activities for increasing hand coordination and strength include tracing, drawing in mazes, and playing with clay as well as exercises like finger tapping and rubbing/shaking the hands. Intervention can also include teaching grip control and good writing posture. However, research has demonstrated that teaching motor skills in conjunction with orthographic skills is the most effective approach (40). One example method of teaching orthographic tasks is described by Berninger (19): the student learns to write each letter by first visually learning the steps to write the letter (based on a sample with numbered arrow cues), then visualizing the act of writing the letter, using the cues to transcribe the letter, and checking the written product with the initial sample (41). Other techniques focus the learners’ attention on the movements associated with writing rather than the written product itself [e.g., reviewing video models instead of static guides (42) and using placeholder pens without ink (43)].

The family should provide enjoyable writing activities outside of the educational setting so that the individual can learn that writing can be a pleasant and enjoyable experience. Research has demonstrated that educational games and activities can be used to help students practice retrieving letters from long-term memory (44).

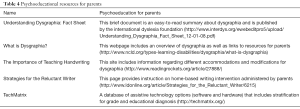

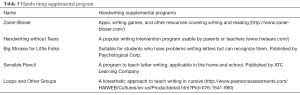

Students with dysgraphia may also need help in more complex parts of writing, including planning, drafting, and revising, especially as they enter the middle and high school years. Randomized-control trials have shown that interventions like “writing clubs” can improve performance in students struggling with these skills. Another validated approach is the self-regulated strategy development program that has shown generalized and sustained efficacy (45). This curriculum specifically instructs in strategies of writing and self-regulation with students acting as collaborators during the course. Students who continue with writing difficulties in middle and high school may require additional specific instruction in composition (46,47). Some psychoeducational programs (Table 4), handwriting programs (Table 5) and support groups (Table 6) are useful resources for children with dysgraphia and their families and other professionals.

Full table

Full table

Full table

Conclusions

Writing is a skill that is central to learning and activities of daily living; it begins to develop in early childhood but continues through the school age. Though common in children, dysgraphia and disorders of written expression are often overlooked by the school and family as a character flaw rather than a genuine disorder. A variety of cognitive mechanisms have been proposed regarding the mechanism of dysgraphia and continued research is needed in the field to clarify the definition and etiology of the disorder. Regardless of the presenting symptoms, early diagnosis and intervention has been linked to improved results. Because of typical delay in the diagnosis of dysgraphia, the primary care provider can play an important role in recognizing the condition and initiating the proper work-up and intervention. Screening for co-morbid medical, neurodevelopmental, psychiatric and learning disorders is also an important function of the provider. Education and support for the family, coordination of care with the educational system, additional referrals to subspecialists, and follow-up screening for co-morbidities are important tasks for the primary care provider to adopt.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: DRP serves as the unpaid Deputy Editor-in-Chief of TP and the unpaid Guest Editor of the focused issue “Neurodevelopmental and Neurobehavioral Disorders in Children”. TP. Vol 9, Supplement 1 (February 2020). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Nicolson RI, Fawcett AJ. Dyslexia, dysgraphia, procedural learning and the cerebellum. Cortex 2011;47:117-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tseng MH, Chow SM. Perceptual-motor function of school-age children with slow handwriting speed. Am J Occup Ther 2000;54:83-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fournier del Castillo MC, Maldonado Belmonte MJ, Ruiz-Falcó Rojas ML, et al. Cerebellum atrophy and development of a peripheral dysgraphia: a paediatric case. Cerebellum 2010;9:530-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deuel RK. Developmental dysgraphia and motor skills disorders. J Child Neurol 1995;10 Suppl 1:S6-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berninger VW. Defining and Differentiating Dysgraphia, Dyslexia, and Language Learning Disability within a Working Memory Model. In: Mody M and Silliman ER. editors. Brain, Behavior, and Learning in Language and Reading Disorders. New York: the Guilford Press, 2008:103-34.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental health disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

- US Department of Education. Topic: Identification of Specific Learning Disabilities. Office of Special Education Programs. Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/Identification_of_SLD_10-4-06.pdf. Accessed 2019 December 12.

- Kushki A, Schwellnus H, Ilyas F, et al. Changes in kinetics and kinematics of handwriting during a prolonged writing task in children with and without dysgraphia. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32:1058-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berninger VW, May MO. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment for specific learning disabilities involving impairments in written and/or oral language. J Learn Disabil. 2011;44:167-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCloskey M, Rapp B. Developmental dysgraphia: an overview and framework for research. Cogn Neuropsychol 2017;34:65-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cahill S. Where does handwriting fit in? Strategies to support academic achievement. Intervention in School and Clinic 2009;44:223-9. [Crossref]

- Amundson SJ, Weil M. Prewriting and handwriting skills. In: Case-Smith J, Allen AS, Nuse Pratt P, editors. Occupational therapy for children. St Louis: C.V. Mosby, 1996:524-41.

- Feder K, Majnemer A, Synnes A. Handwriting: Current trends in occupational therapy practice. Can J Occup Ther 2000;67:197-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sassoon R. Dealing with adult handwriting problems. Handwriting Review 1997;11:69-74.

- Berninger VW, Nielsen KH, Abbott RD, et al. Gender differences in severity of writing and reading disabilities. J Sch Psychol 2008;46:151-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feder KP, Majnemer A. Handwriting development, competency, and intervention. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49:312-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graham S, Perin D. A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. J Educ Psychol 2007;99:445-76. [Crossref]

- Overvelde A, Hulstijn W. Handwriting development in grade 2 and grade 3 primary school children with normal, at risk, or dysgraphic characteristics. Res Dev Disabil 2011;32:540-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berninger V, Vaughan K, Abbott R, et al. Treating of handwriting fluency problems in beginning writing: Transfer from handwriting to composition. J Educ Psychol 1997;89:652-66. [Crossref]

- Connelly V, Campbell S, MacLean M, et al. Contribution of lower order skills to the written composition of college students with and without dyslexia. Dev Neuropsychol 2006;29:175-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gubbay SS, de Klerk NH. A study and review of developmental dysgraphia in relation to acquired dysgraphia. Brain Dev 1995;17:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rapcsak SZ, Beeson PM, Henry ML, et al. Phonological dyslexia and dysgraphia: Cognitive mechanisms and neural substrates. Cortex 2009;45:575-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berninger VW, Wolf BJ. Teaching Students with Dyslexia and Dysgraphia. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co., 2009.

- Grizzle KL, Simms MD. Language and learning: A discussion of typical and disordered development. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2009;39:168-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zoccolotti P, Friedmann N. From dyslexia to dyslexias, from dysgraphia to dysgraphias, from a cause to causes: A look at current research on developmental dyslexia and dysgraphia. Cortex 2010;46:1211-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ito M. Control of mental activities by internal models in the cerebellum. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008;9:304-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molfese V, Molfese D, Molnar A, et al. Developmental Dyslexia and Dysgraphia. In: Whitaker HA, editor. Concise Encyclopedia of Brain and Language. Oxford: Elsvier Ltd, 2010:485-91.

- Berninger V, Richard T. Inter-relationships among behavioral markers, genes, brain and treatment in dyslexia and dysgraphia. Future Neurol 2010;5:597-617. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenblum S, Livneh-Zirinski M. Handwriting process and product characteristics of children diagnosed with developmental coordination disorder. Hum Mov Sci 2008;27:200-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chau T, Ji J, Tam C, et al. A novel instrument for quantifying grip activity during handwriting. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:1542-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Martins MR, Bastos JA, Cecato AT, et al. Screening for motor dysgraphia in public schools. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2013;89:70-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mayes SD, Calhoun SL. Learning, attention, writing, and processing speed in typical children and children with ADHD, autism, anxiety, depression, and oppositional-defiant disorder. Child Neuropsychol 2007;13:469-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Biotteau M, Danna J, Baudou E, et al. Developmental coordination disorder and dysgraphia: signs and symptoms, diagnosis, and rehabilitation. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019;15:1873-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaplan BJ, Dewey DM, Crawford SG, et al. The term comorbidity is of questionable value in reference to developmental disorders: data and theory. J Learn Disabil 2001;34:555-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vedi K, Bernard S. The mental health needs of children and adolescents with learning disabilities. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2012;25:353-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wright P, Wright P. 2008. Child Find. Available online: http://www.wrightslaw.com

- Beery KE, Buktenica NA, Beery NA. Beery-Buktenica Developmental Test of Visual-Motor Integration, 6th Ed. Minneapolis, NCS: Pearson Inc.; 2010.

- Longcamp M, Hlushchuk Y, Hari R. What differs in visual recognition of handwritten vs. printed letters? An fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2011;32:1250-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alamargot D, Chanquoy L. Through the models of writing. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2001.

- Berninger VW, Rutberg JE, Abbott RD, et al. Tier 1 and Tier 2 early intervention for handwriting and composing. J Sch Psychol 2006;44:3-30. [Crossref]

- Graham S, Berninger VW, Abbott RD, et al. Role of mechanics in composing of elementary school students: A new methodological approach. J Educ Psychol 1997;89:170-82. [Crossref]

- Beringer VW, Vaughan KB, Graham S, et al. Treatment of handwriting problems in beginning writers: transfer from handwriting composition. J Educ Psychol 1997;89:652-66. [Crossref]

- Danna J, Velay JL. Basic and supplementary sensory feedback in handwriting. Front Psychol 2015;6:169. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berninger V, Abbot S. PAL research-supported reading and writing lessons and reproducibles. San Antonio, TX: Pearson Assessment, 2003.

- Graham S, Harris KR. Students with learning disabilities and the process of writing: A meta-analysis of SRSD studies. In: Swanson HL, Harris KR, Graham S. editors. Handbook of Learning Disabilities. New York: Guildford Publications, 2003:323-44.

- Chenault B, Thomson J, Abbott RD, et al. Effects of prior attention training on child dyslexics' response to composition instruction. Dev Neuropsychol 2006;29:243-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berninger VW, Winn WD, Stock P, et al. Tier 3 specialized writing instruction for students with dyslexia. Read Writ 2008;21:95-129. [Crossref]